In Part 1, I introduced you to John Dickinson, the “Penman of the Revolution” who became a Forgotten Founder by refusing to vote for independence. In Part 2, I showed you how his 1760s works opposing the Stamp and Townshend Acts made him “America’s first political hero.”

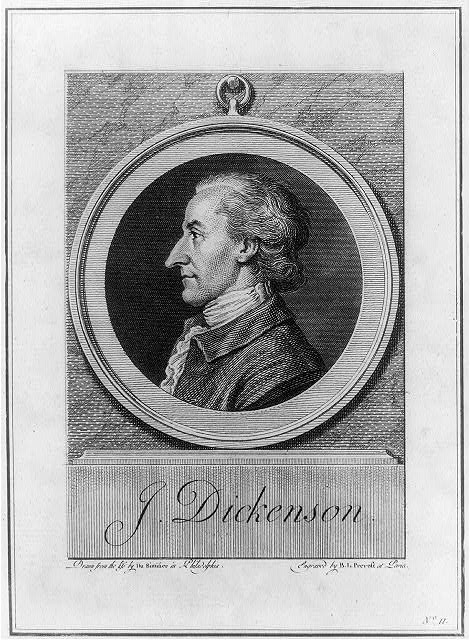

Portrait of John Dickinson, drawn from life and engraved, courtesy the Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-26777

“In the early phase of the conflict, when most were for peace rather than war, Dickinson had the adoration of his countrymen,” noted Jane Calvert. Dickinson’s message—“that resistance should be peaceful, respectful of persons, property, and just laws, and aimed at reconciliation”—was popular for years.

No such thing is desired by any thinking man in all of North America; on the contrary, that it is the ardent wish of the warmest advocates for liberty, that peace & tranquility, upon constitutional grounds, may be restored, & the horrors of civil discord prevented.

— George Washington dismisses independence in an October 1774 letter

But “as the tenor of the times changed to favor independence,… Dickinson did not change with it. He held his position in favor of reconciliation and quickly became viewed as a conservative… [He] did not vacillate from radical to moderate to conservative. It was the sentiment around him that changed,” wrote Calvert.

This shift is reflected in the writings of the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1776. Dickinson was the primary author of four of their 1774 documents and their two most important 1775 documents. “Congress recruited its best writers for the committees that drafted its public pronouncements. Dickinson… remained the best-known and most celebrated American political writer,” noted Pauline Maier.

1774—First Continental Congress

The die is now cast. The colonies must either submit or triumph.

— George III letter to Prime Minister Lord North, September 1774

In 1774, Parliament passed the Coercive or Intolerable Acts to punish Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party and bring the colonies under control. These laws, in part, closed the port of Boston, commandeered private houses for quartering soldiers, and put Massachusetts officials under the control of Britain.

In response, twelve of the thirteen colonies (all except Georgia) sent 56 delegates to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, which met in September and October. They hoped to reconcile with the king and restore violated colonial rights and liberties. Congress adopted the Association, an agreement to boycott trade with Britain if the Coercive Acts were not repealed.

Though Dickinson wasn’t elected until October, he drafted four of their six documents, most notably:

- Declaration and Resolves (Declaration of Rights and List of Grievances), which defined and asserted the rights of the colonists based on “the immutable laws of nature” and “the principles of the English constitution.” This important precursor to the Declaration of Independence and the state declarations of rights stated that Americans were entitled to all English liberties, including “life, liberty, and property,” representation and participation in their own government (especially in issues of taxation and internal policy), and trial by jury.

- A Letter to the Inhabitants of the Province of Quebec, which “explains more fully the principles of English constitutional liberty and their foundation in English law than any on the same subject in the language,” noted Charles Stillé.

- The Petition to the King, which Stillé described as “a clear and logical statement of our grievances, and in dignified expression of lofty political sentiment… it is unsurpassed by any state paper issued during the Revolution.”

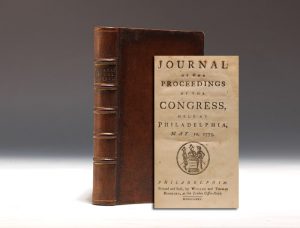

After Congress adjourned, William and Thomas Bradford published the Journal of the Proceedings of the Congress from the official minutes. A work of great rarity, it is one of the earliest publications of the new government, preceded only by Bradford pamphlets containing partial extracts.

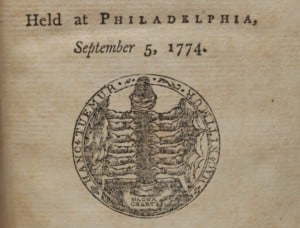

The printers designed a title page seal, which Edwin Wolf 2nd called “the first attempt to represent emblematically a united nation”—a pillar held by twelve hands standing on the Magna Carta, with the motto “Hanc Tuemur, Hac Nitimur,” or “this we defend, by this we are protected.”

1775—Second Continental Congress

…prepare for a vigorous defensive War, but at the Same Time to keep open the Door of Reconciliation—to hold the sword in one Hand and the Olive Branch in the other….

— John Adams letter, June 1775

All thirteen colonies sent representatives to the Second Continental Congress in May 1775, shortly after Lexington and Concord. The delegates were deeply divided, but neither they nor the colonists were ready to embrace independence.

On July 5, Congress adopted Dickinson’s Olive Branch Petition, a letter to George III asking for the last time to hear their grievances and avoid more bloodshed. “Dickinson saw the Olive Branch Petition as a vital tactical maneuver. If the British accepted it, America would secure its liberties without further bloodshed. ‘If they reject this application with contempt,’ he wrote, ‘…such treatment will confirm the minds of our countrymen to endure all the misfortunes that may attend the contest.’ A rejection, in other words, would unite the Americans as never before,” noted David Lefer.

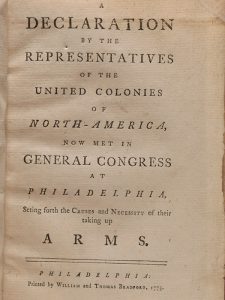

The next day, Congress issued one of its greatest state papers, the Declaration… Setting forth the Causes and Necessity of taking up Arms. Written by Jefferson and Dickinson in what Calvert described as “a tense collaboration,” it is a strong statement of grievances, a plea for peace and reconciliation, and justification of their armed resistance. It was first printed as a pamphlet by the Bradfords, and it appeared in contemporary pamphlet, newspaper, and broadside printings, all of which are very rare.

Our cause is just. Our union is perfect…. [The] arms we have been compelled by our enemies to assume we will… employ for the preservation of our liberties; being with one mind resolved to die free men rather than live slaves… We have not raised armies with ambitious designs of separating from Great Britain establishing independent states… In our own native land, in defense of the freedom that is our birthright, and which we ever enjoyed till the late violation of it—for the protection of our property,… against violence actually offered, we have taken up arms.

This was Jefferson’s first writing assignment for Congress, noted Pauline Maier:

Dickinson, the senior man, offered various criticisms of Jefferson’s manuscript… [After Jefferson] rejected most of his suggestions, Dickinson prepared another extensively revised draft, which Congress approved with minor changes on July 6, 1775. In later years Jefferson claimed his composition had been ‘too strong for Mr. Dickinson,’ who ‘retained the hope of reconciliation with the mother country…’ He forgot that in mid-1775, he, too, had hoped for reconciliation… Dickinson, in fact, had made Jefferson’s draft stronger, more assertive, even threatening…. [and] raised the possibility of Independence more explicitly than Jefferson had done. But Independence, the Declaration… emphasized, was not what the colonists wanted.

After Congress adjourned in September, the Bradfords printed the Journal of its 1775 proceedings, which contains both of these important documents.

By the end of 1775, George III had rejected the Olive Branch Petition, declared the colonies in rebellion and announced he would subdue them by force, and issued a proclamation that would close the colonies to all commerce and trade. In 1776, as the conflict heated up and Thomas Paine’s Common Sense swept through America, Congress chose independence and Dickinson found himself on the wrong side of history.