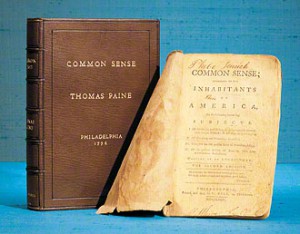

In Part 1, I explored the controversy over whether Thomas Paine was a Founding Father. This post is about Common Sense, his most famous work and the most influential, brilliant, and best-selling pamphlet of the American Revolution.

The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind… In the following pages I offer nothing more than simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense… The Sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. ‘Tis not the affair of a City, a County, a Province, or a Kingdom, but of a Continent… ‘Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected, even to the end of time, by the proceedings now. Now is the seed-time of Continental union, faith and honour.

— Thomas Paine, Common Sense

“How an unknown and uneducated Englishman who had been in the colonies for little more than a year came to write the most influential essay of the American Revolution… is a mystery not easily solved,” Jill Lepore observed. No one—not even Paine—could have foreseen it.

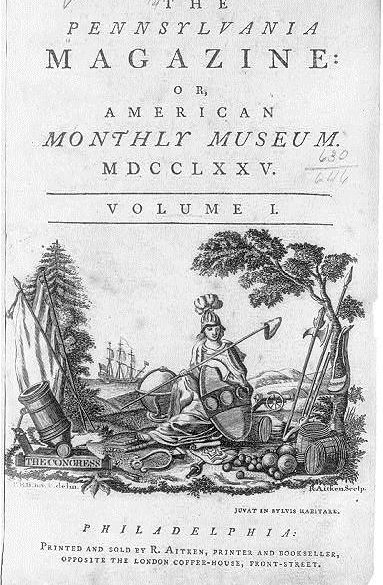

In February 1775, Paine was hired by printer Robert Aitken to be the editor of the new Pennsylvania Magazine, which covered topics from current events to literature to science. Paine also wrote (under pseudonyms) many of the articles in the February through August issues, where he “found both his audience and his voice,” wrote Edward Larkin.

Paine recalled later that when he came to America:

I had no thought of independence or arms. The world could not then have persuaded me that I should be either a soldier or an author… Scarcely had I put my foot into the country but it was set on fire about my ears.

It was Lexington and Concord in April 1775 that “converted Paine to the doctrine of Independence,” noted Vikki Vickers. Later that year his friend Benjamin Rush encouraged him to write an essay on independence. Rush decided against writing one himself because he feared for his reputation and safety, but thought Paine “had nothing to fear from the popular odium to which such a publication might expose him, for he could live anywhere.” Paine agreed to write it but ignored Rush’s warning not to use the dangerous words “independence” and “republicanism.”

Bernard Bailyn commented that “one had to be a fool or a fanatic in early January 1776 to advocate American independence,” as it “was not the common opinion of the Congress, and it certainly was not the general view of the population at large.” Vickers noted:

Reconciliation was a matter of public debate; independence was not… [Paine] wanted to convince Americans that there was only one option—complete and absolute independence… He used prevailing Enlightenment natural law political theory to appeal to Americans’ reason, and inflammatory anti-British rhetoric to appeal to their emotions… The American struggle was a battle between good and evil, and Paine exhorted the American people and the Continental Congress to act boldly.

Common Sense was published anonymously on January 9, 1776, in Philadelphia where the Continental Congress was meeting. Its “delegates—independents, Tories, and moderates alike—were among its most avid readers. After reading and discussing Common Sense among themselves, delegates eagerly became self-appointed publicists and distributors for the anonymously published work. In sending copies back to their friends and families, most delegates expressed approval of the pamphlet’s ideas, and many even pronounced themselves convinced by its eloquent advocacy for separation,” wrote Scott Liell.

Have You seen the pamphlet Common Sense? I never saw such a masterly irresistible performance—it will if I mistake not, in concurrence with the transcendant folly and wickedness of the Ministry give the coup de grace to G. Britain—in short I own myself convinc’d by the arguments of the necessity of separation.

— January 24, 1776 letter from Charles Lee to George Washington

As the pamphlet quickly spread throughout the colonies, “Common Sense and Independence” became a rallying cry. Stories about it even appeared in London—Almon’s Remembrancer printed a March 1776 letter from Philadelphia reporting that Common Sense “is read to all ranks; and as many as read, so many become converted, though perhaps the hour before were most violent against the least idea of Independence.”

You can read about the 1776 publication history of Common Sense in my earlier post on American pamphlets.

Read Part 3 on Thomas Paine here.

Comments

One Response to “Forgotten Founders: Thomas Paine, Part 2”

tom blumenthal says: March 16, 2023 at 11:17 pm

Thank you