So you want to learn about rare books? Welcome to Rare Books 101. In this mini-course we will be covering all the fundamentals of collecting to help you in your journey to build the perfect personal library.

Written by Rebecca Romney

Part I: Frequently Asked Questions

What is a rare book?

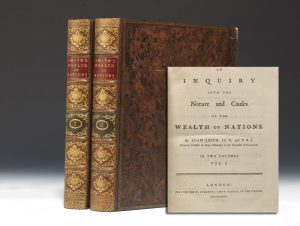

In a nutshell, it is a book that is collected. “Rare” in this case does not mean “scarce”—though that is generally part of it.

What books are most likely to be collected?

First editions.

Why?

Basic supply and demand.

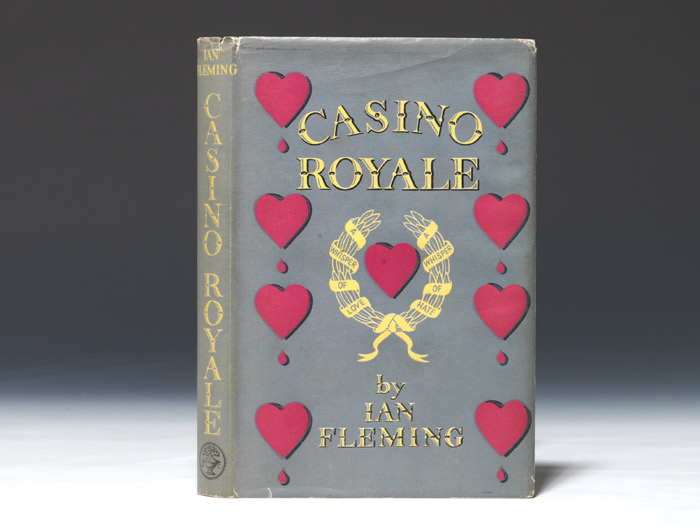

Supply: In most cases, the first edition of a book is the version that is printed in (and survives in) the fewest amount of copies. This is because the first time a book is printed, the publishers won’t have a certain idea of how well it will sell, so they tend towards conservative in the number of copies they print. That way there’s no harm: if the print run sells out, they can always print more. On the other hand, if they print too many and copies of the print run are left over, the publisher loses money. Therefore it’s safer to make your first print a relatively small number.

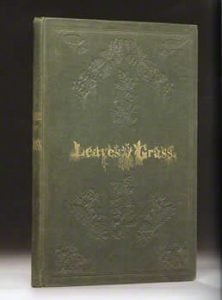

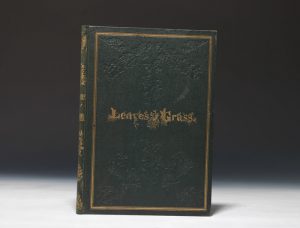

Demand: The first edition of a book is generally the edition that has the biggest impact on the world. In addition, there’s a romanticism to the idea that it’s the first time those ideas were ever read by the general public. Collecting is very concept-driven, and collectors often seek items with the greatest historical or personal impact.

Note that supply and demand work together. You might own a book that survives in only three copies, but if no one is interested in the content, it won’t be a terribly valuable book. On the other hand, if a book in high demand is printed in an enormous amount of copies, its collectible value will be relatively lower than expected, given its impact.

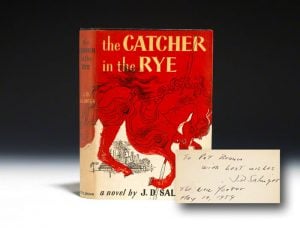

Signed books are another example of the supply and demand concept. If there are already few copies of a first edition, then there are even fewer first edition copies that are also signed. In addition, a book that is signed will be in higher demand because of the concept that the author actually touched the book.

How can I tell if my book is a first edition?

There is no uniform way to tell, as printing conventions vary widely from era to era and place to place. The ideal is obviously when the book says “first edition,” generally on the copyright page. However, this trait is seen most often only with books printed after WWII, so for the vast majority of rare books it will not appear.

Collectors search for what are called bibliographic points. Think of a point as a point of change. That is: in earlier copies of a book, a physical trait shows itself one way. Then a change occurs, and that physical trait shows itself differently.

An easy example of this is a typo. On page 57 of Huckleberry Finn, 11 lines up from the bottom, the text reads: “with the was.” It should read: “with the saw.” This was caught after the first printing and corrected, so bibliographers know that any copies with the error are part of the first printing.

Points can be more than simply errors, however. Maybe the book was bound in a different color in later editions. Maybe the publisher increased the price of the book where it was printed on the dust jacket. There are practically limitless possibilities, and each book is different. In other words: you need to ask an expert or consult the proper bibliography to know for sure.

But my book looks just like the one on your website. Doesn’t that mean it’s a first?

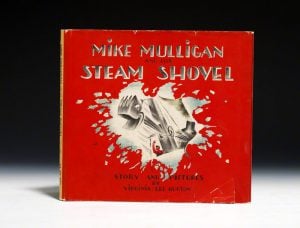

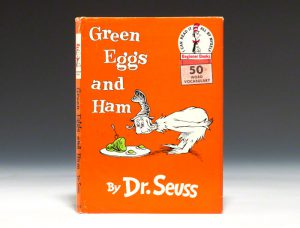

This is a leading question, but we get it all the time. The answer is no. Many books—particularly 20th century and children’s books—are published with the same artwork and in the same format over and over again.

Think about it this way. You loved Mike Mulligan and his Steam Shovel when you were little. Now you have a child. You want to buy him a copy that looks just like the one you had. See, it’s quite smart for publishers to keep the same art in some cases.

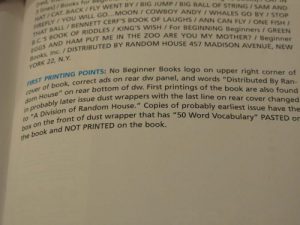

Instead, you have to search out those bibliographic points. Is the rectangle in the corner reading “50 Word Vocabulary” on Green Eggs and Ham a sticker, or printed on the book? That’s one point for this iconic Seuss title: the rectangle is a sticker.

How do I figure out the bibliographic points of a first edition?

In the end, it’s always about the authoritative bibliography. A bibliography is an in-depth description of the physical aspects of a book, usually emphasizing the differences (the points) so as to make identifying the proper edition as simple as referencing the information in the book.

Besides entire books of dedicated bibliographies, there are a lot of books whose bibliographies are summarized in individual articles. In addition, there are some handy one-stop guides available—though these are more useful for a quick list of points. But beware: They do NOT always cover every important point of a book, and are not terribly useful for accurate pricing of a specific book, which is simply more nuanced than a single number.

Ask an expert at Bauman when in doubt. We will either help you find the bibliography, or we will look it up ourselves in the bibliography and let you know.

Comments

5 Responses to “Rare Books 101, Part I: FAQ”

matt Howard says: July 17, 2013 at 1:35 pm

First class infomation and easy to follow explanations about rare 1st Editions and all antiquarian book collecting thanks.

Emma says: March 9, 2014 at 5:54 pm

i have an edition of Jane Eyre by Currer Bell, its published by Richard Edward King; 88, Curtain Road, E.C. my only problem is that i don’t know which edition it is, or if its of little worth, i know it isn’t a first addition as it states under “CURRER BELL” (Charlotte Bronte). Its a hardback book with a maroon color, it has no printed date so i can not tell when it was printed, there’s a small pencil note on the 1st page saying (1890 edition) but i do not know whether to believe it. Any help?

Cahd says: April 11, 2014 at 11:23 am

You all need a section in “Rare Books 101” about signed books, i.e., is it better to 1) get a single signature vs. a personalized signature, 2) to use and acid free pen, 3) to have the signature in black ink, 4) fine line signature or bold line signature?

Rebecca Romney says: August 15, 2014 at 10:40 pm

If that collection were published by the first time by Doubleday, one would call that the “first Doubleday edition,” but calling that “first edition” with no extra qualifiers would be incorrect.

Sometimes editions other than the very first ever printed will become collectible as well, although this is somewhat unusual. For instance, we will refer to “true firsts,” emphasizing the very first version when other “firsts” are still collectible–such as the first American edition of Alice in Wonderland vs. the “true first,” the one published in London and recalled by Carroll/Tenniel.

Jessica Gray says: November 2, 2014 at 2:35 pm

I have a copy of Green Eggs and Ham that is bound upside-down and 1st page is at the back of the book also, pages are uneven.