“Who is John Galt?”

With this question, Ayn Rand began her final novel, Atlas Shrugged, one of the most controversial, influential, and bestselling books of the 20th century. It’s a page-turner that combines (in Rand’s own words) “metaphysics, morality, economics, politics, and sex,” as well as “a mystery story, not about the murder of man’s body, but about the murder—and rebirth—of man’s spirit.”

The popularity of Atlas Shrugged has only continued to grow since its publication in 1957, as new generations discover it and prominent politicians, economists, and CEOs cite it as their favorite book, one that changed their lives or shaped their philosophies.

The story of Ayn Rand’s life is as unlikely as the plots of the old Hollywood movies she loved. Born in St. Petersburg in 1905 to Jewish parents, Alice (or Alisa) Rosenbaum and her family suffered severe hardships after the 1917 Russian Revolution. She became an atheist in high school, and at university she studied history and philosophy, where she read the works of writers who greatly influenced her, including Aristotle, Plato, Friedrich Nietzsche, Victor Hugo, and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

She was determined to escape Soviet Russia, move to the United States, and become a screenwriter, and she did. Shortly after arriving in America in 1926, she changed her name (inspired by her Remington-Rand typewriter) and went to Hollywood. A chance meeting with Cecil B. DeMille got her jobs as an extra on his movie The King of Kings and a junior screenwriter in his studio. On the set she met her future husband, Frank O’Connor. They married in 1929 before her visa expired, and she became an American citizen in 1931.

She wrote screenplays, plays, and novels but didn’t achieve real success until The Fountainhead was published by Bobbs-Merrill in 1943 after numerous rejections. It became an immense bestseller and a movie starring Gary Cooper and Patricia Neal, for which she wrote the screenplay.

It took Rand twelve years to write Atlas Shrugged. Her early title was The Strike, as this dystopian novel explores what would happen if all of the creative “men of the mind” went on strike against the collectivist governments destroying their economies and the world.

The novel is a full-throated defense and celebration of capitalism, and its heroes are businessmen, inventors, and creators. “Dagny is myself, with any possible flaws eliminated,” Rand noted, but it’s John Galt, her perfect hero, who espouses Rand’s Objectivist philosophy throughout the novel, most notably in his climactic 60-page speech, which ends:

I swear—by my life and my love it it—that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine.

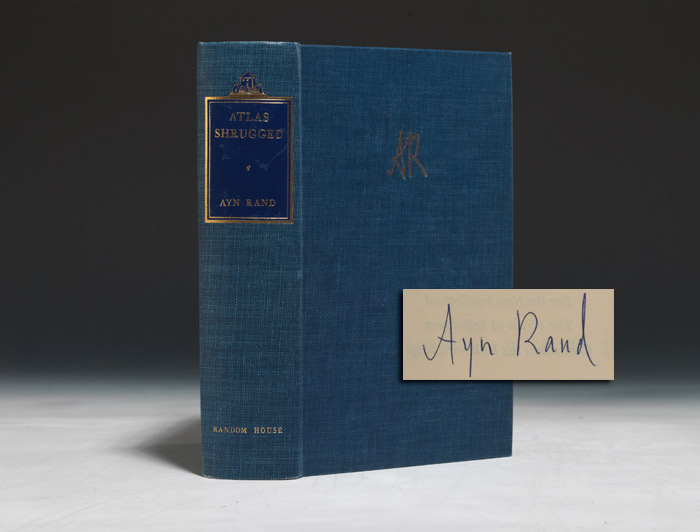

She refused to publish her new book with Bobbs-Merrill—they believed it was too long, “unsaleable and unpublishable.” She refused to discuss changes or cuts and insisted that the book be published “exactly as it is.” After interrogating many publishers, she chose Random House. “It’s a great book. Name your terms,” Bennett Cerf told her.

True to her word, Rand refused to allow any changes to the manuscript. “Would you cut the Bible?” she asked her editor when he wanted to cut down Galt’s speech. She did work closely for months with Random House’s chief copyeditor, Bertha Krantz, who noted: “We were dealing with a manuscript that was more than a thousand pages long—and there were discussions about every comma, every semicolon, every word I questioned. Everything had to be explained to her in painstaking detail, and, according to her philosophy, had to be rational.”

At a Random House sales conference she was asked “could you give the essence of your philosophy while standing on one foot?” She did: “Metaphysics—objective reality; Epistemology—reason; Ethics—self-interest; Politics—capitalism.”

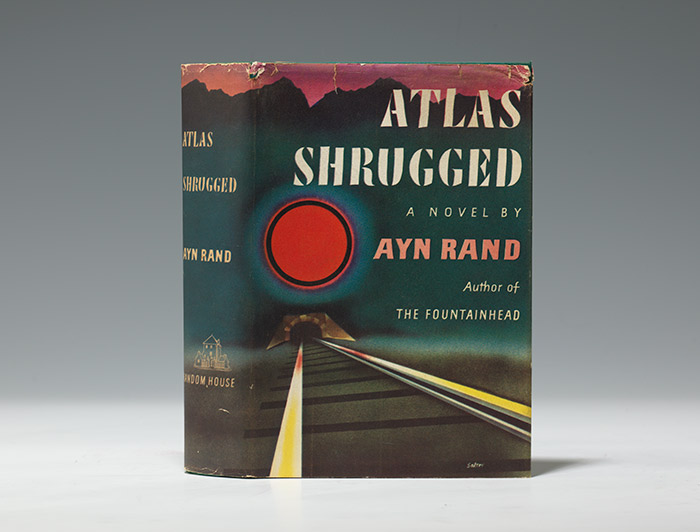

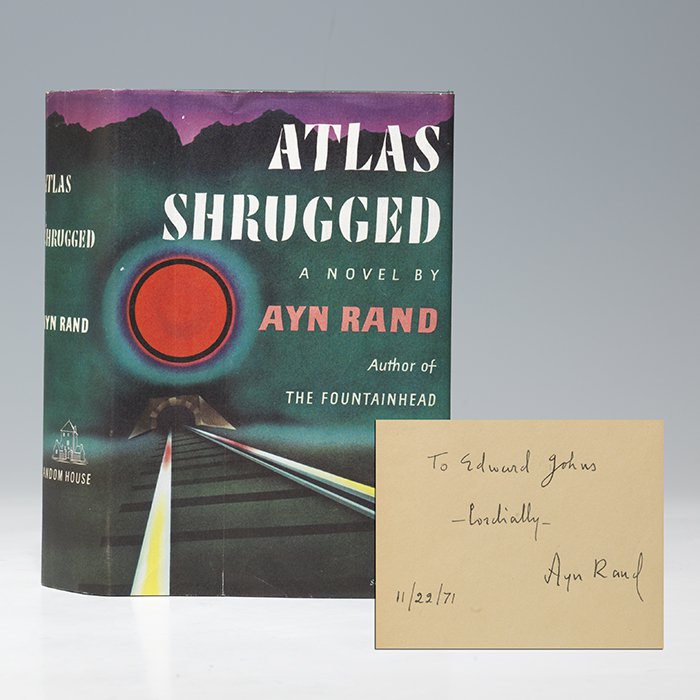

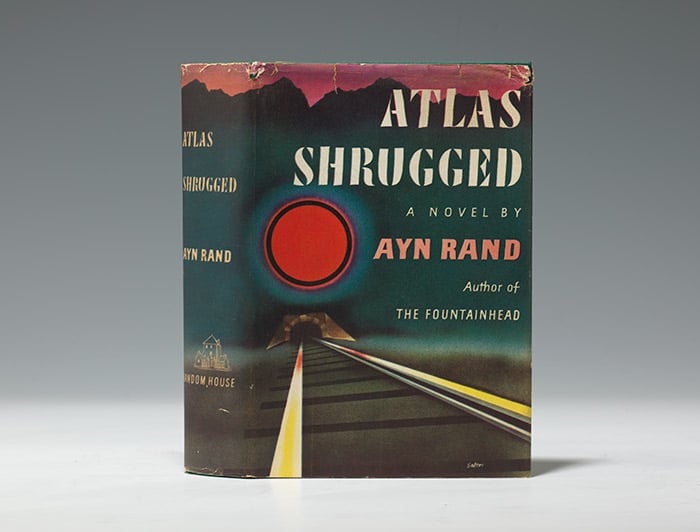

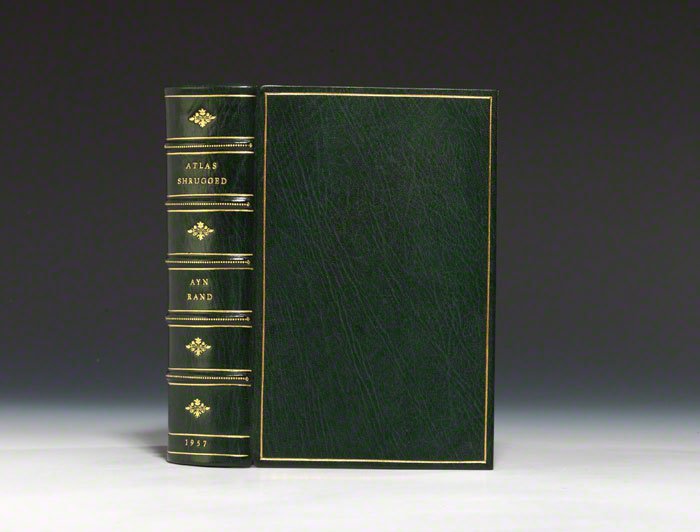

Atlas Shrugged, all 1168 pages of it, was published on October 10, 1957, with a dust jacket designed by George Salter and illustrated by Rand’s husband.

Though many of the reviews were famously hostile, the book quickly became a bestseller and remained on the New York Times list for months. More than a million copies were sold in the first five years, and over eight million copies have sold since its publication. It still sells hundreds of thousands of copies a year, and sales spiked significantly during and since our recent Great Recession.

Of all my teachers, Arthur Burns and Ayn Rand had the greatest impact on my life… Ayn Rand expanded my intellectual horizons, challenging me to look beyond economics to understand the behavior of individuals and societies.

– Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, in his 2007 memoir The Age of Turbulence

Readers selected it as the book that had most influenced their lives (after the Bible) in a 1991 poll by the Library of Congress and Book-of-the-Month Club. It was number one in Modern Library’s 1998 reader’s poll of the 100 best novels of the 20th century.

Jennifer Burns explained the novel’s extraordinary and continuing appeal to the business world:

The book made Rand a hero to many business owners, executives, and self-identified capitalists, who were overjoyed to discover a novel that acknowledged, understood, and appreciated their work… She presented a spiritualized version of America’s market system, creating a compelling vision of capitalism that drew on traditions of self-reliance and individualism but also presented a forward-looking, even futuristic ideal of what a capitalist society could be… Rand’s defense of wealth and merit freed capitalists from both personal and social guilt simultaneously… In Rand business had found a champion, a voice that could articulated its claim to prominence in American life.

Browse our Ayn Rand first editions

Sources and further reading:

- Barbara Branden’s 1986 book The Passion of Ayn Rand

- Jennifer Burns’ 2009 book Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right

- Anne C. Heller’s 2009 book Ayn Rand and the World She Made

- Harriet Rubin’s 2007 New York Times article, “Ayn Rand’s Literature of Capitalism”