In the first part of this miniseries, Las Vegas bookseller Greg Hicks reveals why the printing in English of the Bible changed the world forever.

While the importance of the Bible as a religious, historical, and literary document is widely acknowledged, the immense importance of the Bible in English may not be readily apparent.

Its importance is due in large part to a single simple fact: without vernacular translations of the Bible (including English-language versions) the Protestant Reformation in Europe would have been unthinkable.

A brief look at the Reformation will clarify this. The central aim of the Protestant reformers was to recover and resuscitate Christianity in its original, unalloyed form, unencumbered with the doctrines, dogmas, rituals, customs, and institutional practices of the Roman Catholic Church. A classic example of this was the sale of indulgences, which Martin Luther excoriated as un-Christian and un-Biblical in the early 16th century.

The reformers believed that “true” or “genuine” Christianity would begin to re-emerge if ordinary believers had direct access to the Scriptures, unencumbered by the doctrinal and ceremonial encrustations of the Catholic Church. This meant translating the Old and New Testaments into the languages that believers used in their day-to-day lives. Prior to the Reformation the Bible was generally available in a single version only: the Latin translation which St. Jerome completed around 400 AD (known as the Vulgate). The average Christian, unschooled in Latin, was incapable of reading or understanding this version, and generally knew the Scriptures only through the presentation of selected passages by Catholic clergy in weekly sermons and the like.

In the reformers’ view, the ability of the Christian laity to read and hear vernacular translations of the Scriptures would change everything. The faithful would encounter Christianity in its original, pristine form. The “living waters” of Scripture would foster new forms of personal piety, worlds away from the rote practices of the institutional church. At the same time believers would see for themselves that many of the cardinal teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church (e.g. the doctrine of purgatory, the cult of the Virgin, praying to the saints, and the accumulation of wealth and worldly power by the Church and individual clergy) had no foundation in Scripture, and therefore lacked legitimacy. In the reformers’ view, the availability of vernacular Bibles would shake the foundations of the institutional church, and usher in a new age of revitalized Christian spirituality.

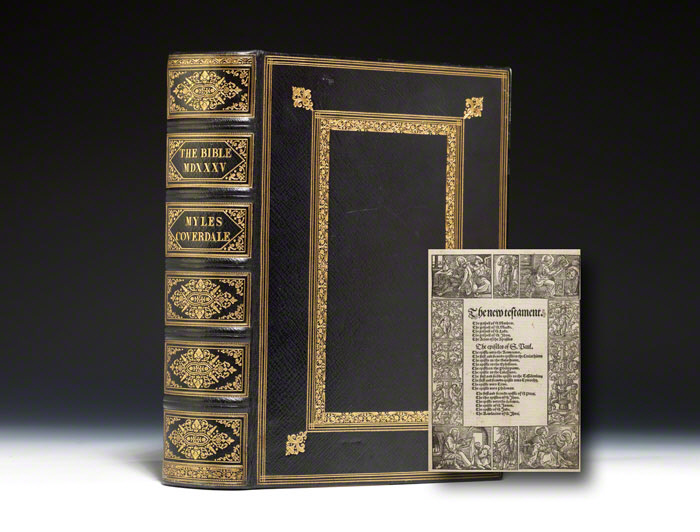

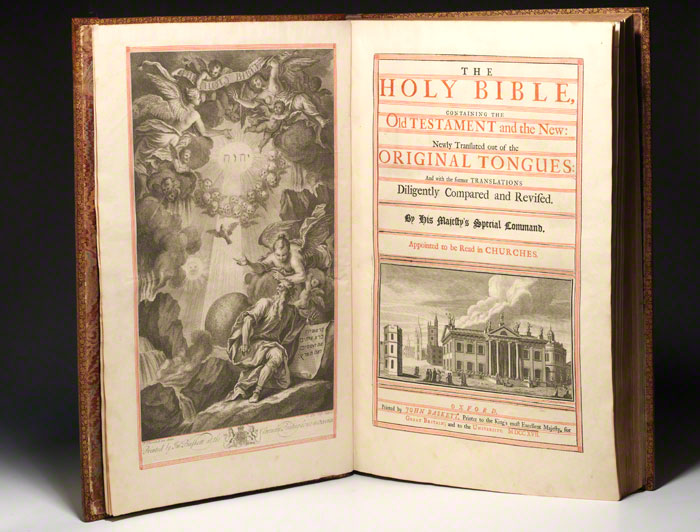

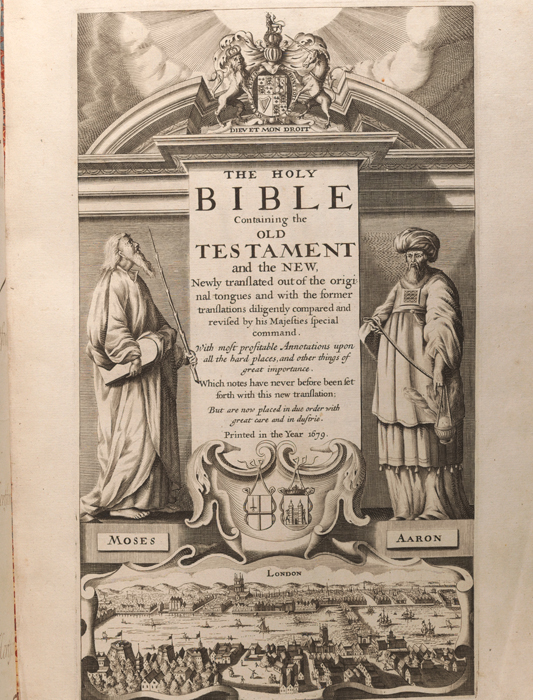

This is the framework in which we should view the evolution of the Bible in English. It was part and parcel of a sea change in Western religiosity whose effects are still very much with us. And it’s the reason why the Bible in English is one of the most engaging and endlessly fascinating subject areas in the world of rare books.

Next week: Which translations matter? The origins and evolution of the Bible in English.