In the second part of his mini-series, The Bible in English, Las Vegas bookseller Greg Hicks explores the translations that matter.

The story of the Bible in English becomes even more intriguing when you look more closely at its origins and evolution. Massive tomes have been written about the subject, but there are a number of high points that are essential to the story.

- The first important translation of the Bible into English was undertaken by John Wycliffe and his followers in the 1380’s. Wycliffe, a theologian at Oxford University, felt that the worldliness and excessive wealth of the late medieval Church would dissipate if believers could read the Gospels for themselves, with their straightforward accounts of the simple, God-centered lives of Jesus and his Apostles. Because of these views Wycliffe has frequently been called “the morning star of the Reformation.” As they gained in popularity his teachings panicked the ecclesiastical authorities, and the mere possession of a Wycliffe Bible was officially condemned as heresy in the 15th century. To reinforce the point, Wycliffe’s remains were exhumed and burned, and his ashes thrown into the River Swift. Since the Wycliffe Bible appeared long before the invention of the printing press in the 1450’s the few copies that have survived are handwritten manuscripts rather than printed books.

- As a direct result of the suppression of Wycliffe’s version, nearly a century and a half elapsed before another important English-language translation appeared. This was the work of the greatest figure in the history of the English Bible, William Tyndale. In addition to being a first-rate linguist (he translated the New Testament from the original Greek and the Old Testament from the original Hebrew), Tyndale was a masterful prose stylist. His facility with language is evident in an oft-cited remark, which captures the essence of the Reformation in a few pithy words: responding to a comment by a recalcitrant priest, he said that “If God spare my life, ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the scripture than thou doest.” Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament appeared in 1526, and was immediately condemned by the English religious authorities. Due in part to the wholesale suppression of this edition only two copies have survived, both incomplete. His translations of the Pentateuch and Johah appeared in 1530 and 1531, respectively. On October 6, 1536 Tyndale was put to death for his English-language translations and his sympathy with the Reformation in general. As he was led to the stake (to be strangled with a chain, then burned) he shouted “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes.”

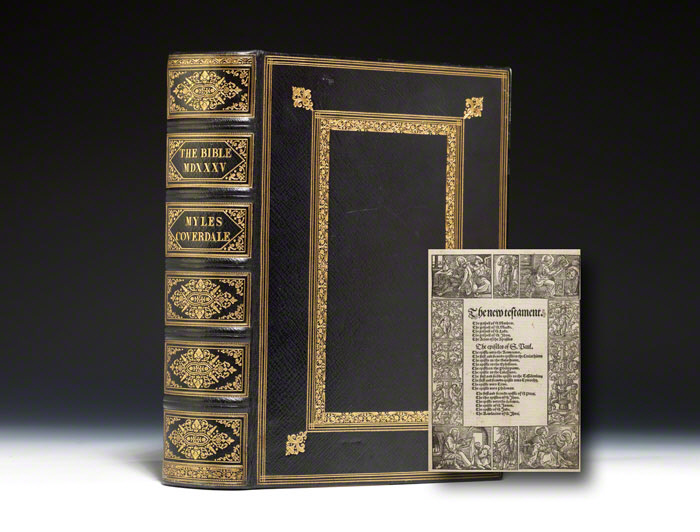

- During his lifetime Tyndale published the New Testament and parts of the Old Testament, but it fell to Miles Coverdale to produce the first complete Bible in English. (see first image) His version was printed overseas, in Antwerp, in 1535. He used Tyndale’s translations almost word for word, and added his own translations (from earlier German and Latin editions) to complete the project. His lyrical prose style resulted in many finely-wrought passages, especially in the Book of Psalms. (As a result, his version of the Psalms was incorporated into the Book of Common Prayer, the official liturgy of the Anglican Church, in 1559.) Fortunately Coverdale wasn’t martyred for his efforts, but he was deprived of his position as Bishop of Exeter when Queen Mary attempted to reinstitute Catholicism in England, beginning in 1553. First edition copies of his Bible are among the great rarities in this subject area. Only about sixty-five survive, all imperfect. As was often the case, his edition was soon superseded by another milestone in the history of the English Bible.

- This new translation, commonly referred to as Matthew’s Bible, was the work of John Rogers, a friend of Tyndale, who used Thomas Matthew as a pseudonym. Rogers’ main contribution was the inclusion of translations by Tyndale which had not appeared in earlier editions. Before his death Tyndale entrusted Rogers with all of the Old Testament translations that he had completed but not published (probably the whole of the Old Testament from Joshua to Chronicles). Rogers combined these with Tyndale’s published translations and portions of Coverdale’s Bible to produce a complete English-language version. Since so much of Tyndale’s work was eventually incorporated into the King James Bible of 1611, Rogers’ edition is generally considered the main precursor of the King James Version. Rogers’ edition was published in Antwerp in 1537. By this time Henry VIII had embraced many of the central tenets of the Reformation, and he licensed Rogers’ edition, making it the first English-language Bible to receive official approval from the English monarchy. However, after Queen Mary assumed the throne in 1553 Rogers was summarily condemned and martyred as a heretic. Translating the Bible into English was, indeed, a matter of life and death in the early years of the English Reformation.

- Stepping back again into the era of Henry VIII, the next great English Bible was the so-called Great Bible of 1539. This Bible was not merely licensed by Henry, it was produced under the auspices of his secretary Thomas Cromwell. Their main aims were to produce a sumptuous Bible with the imprimatur of the monarchy, and a version which would heal the growing rift between the moderate and radical wings of the Church of England. This edition was edited and translated by Miles Coverdale, who (as we have seen) produced the first complete Bible in English a few years earlier. Upon completion, Henry issued an official order, requiring that this edition of the Bible be placed in every church, in a “convenient” and “commodious” setting, so the laity would have easy access to it. As a result of this injunction, and the resulting demand for the Great Bible, seven editions were published between 1539 and 1541.

Next week Greg will continue with the translations that matter and examine the Geneva and King James Bibles among others.