In the final part of his miniseries on the Bible in English, Las Vegas bookseller Greg hicks offers advice on how to build a collection and where to start.

Imagine you’re a potential collector, or someone who’s just gotten started. What are your options?

Fortunately, there are many points of entry for you, and many different ways of structuring your collection.

For example, you might want to start with a fine 17th century King James Bible, since it’s generally considered the finest English-language translation ever produced.

Another focal point might be a 16th or 17th century Geneva Bible, because it contributed so powerfully to the ferment of religious ideas in the early modern period.

You might wish to move on to other key translations, such as the Great Bible, Bishop’s Bible, Rhemes New Testament, or Douai Old Testament, though a few (e.g. Coverdale) are so scarce that they rarely show up on the market.

On the other hand, you may wish to focus on a particular translation (e.g. the King James Version) and collect examples published in different geographical areas or various historical periods. A collection like this would illustrate the enormous spatial and temporal reach of this particular translation, and the way it has “spoken” to believers in a wide range of historical and cultural contexts.

Beyond these basic collecting strategies you can go in many different directions, based on your individual proclivities.

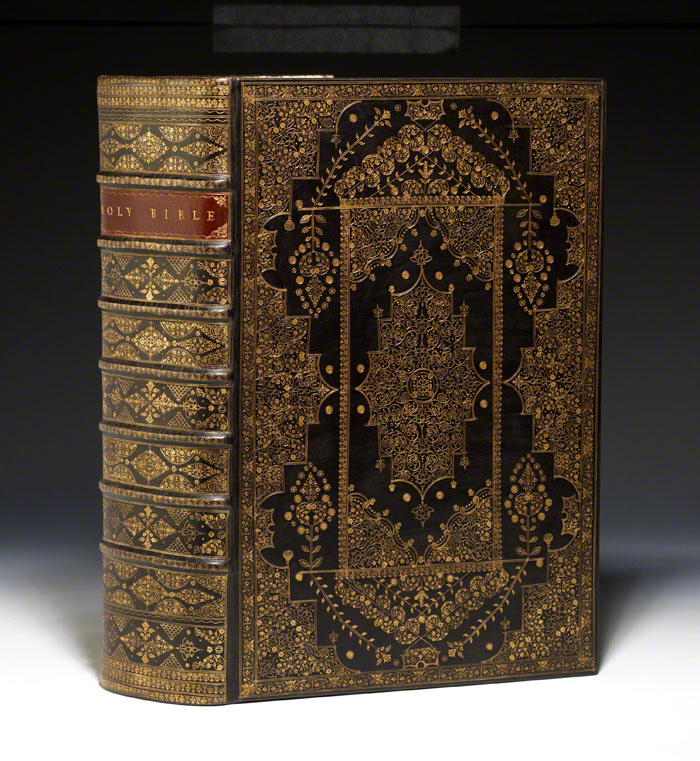

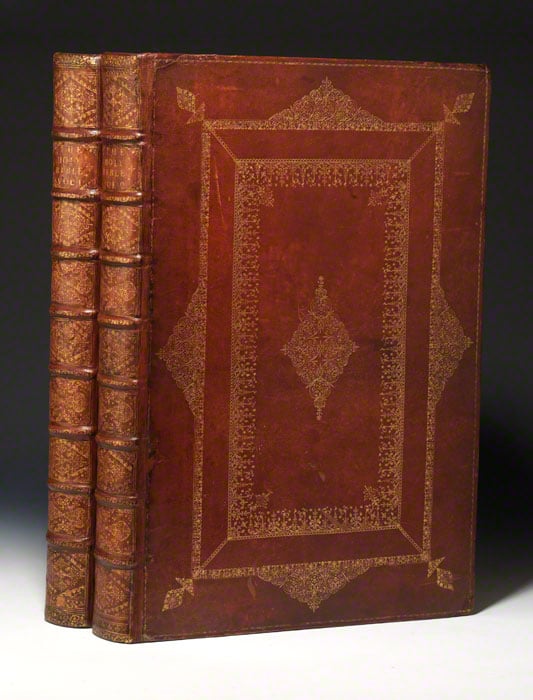

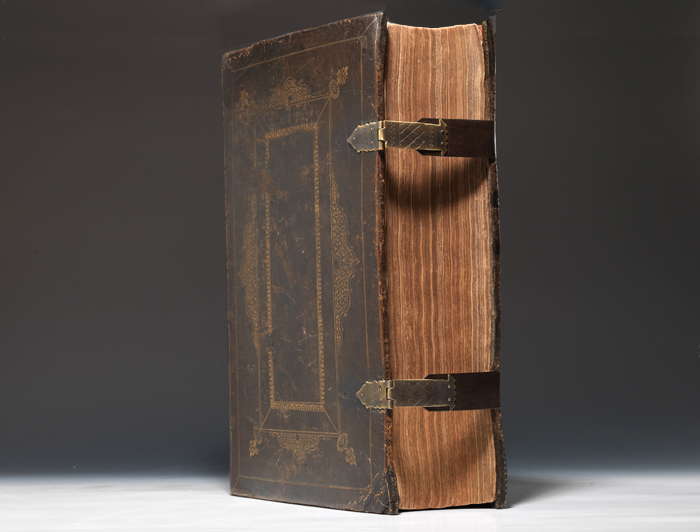

For example, you may wish to collect copies with particularly beautiful bindings. Prior to the 19th century books were commonly sold as stacks of sheets, which the buyer would take to a bindery (often located near the bookseller) to have them bound to order, usually in calfskin or sheepskin. Some of these leather bindings are exquisitely decorated with hand-tooled designs. These were occasionally worked with gold leaf, which further enhanced their aesthetic appeal. A similar sense of luxury was imparted by hand-embroidered covers, which display a wide range of imagery and decorative motifs. Books bound in this fashion are wonderful examples of books as aesthetic objects, not just containers for words.

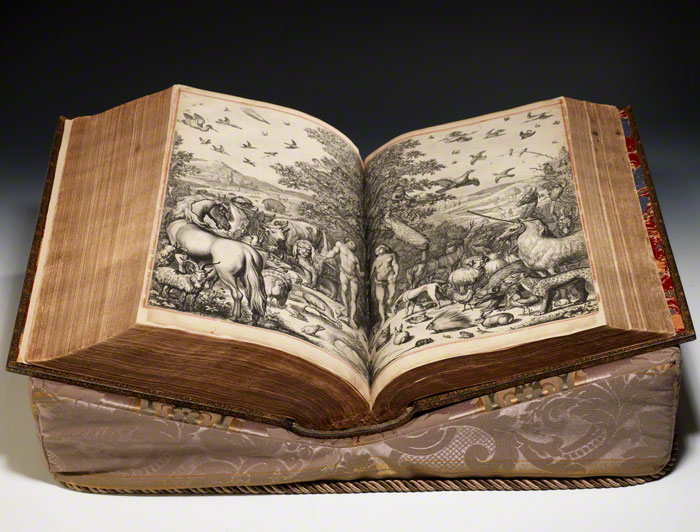

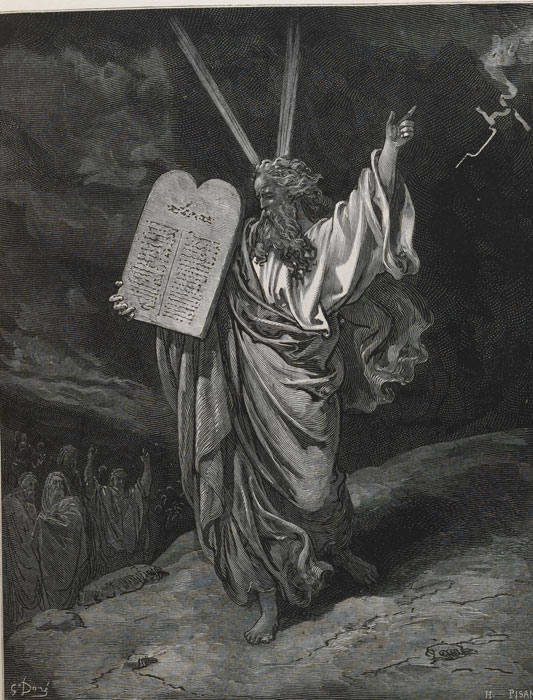

Another area you might want to focus on is illustrated English Bibles. A magnificent example is the seven volume Macklin Bible, first published in 1800, with 70 full-page copper-engraved illustrations, based on designs by the greatest painters in Britain. Another example is the massive two volume folio Bible illustrated by Gustave Dore and first published in English in 1867. It contains 238 full-page wood-engravings by Dore, one of the greatest book illustrators of all time.

You might also want to pursue the theme of family Bibles. Prior to the 20th century, and especially in more remote areas, the Bible was often the only book in the house. Families turned to their Bibles for edification and inspiration, and children often learned to read from them. They frequently contain handwritten family records of births, deaths, marriages, and the like. It’s quite possible that a family Bible you’re holding in your hands was used by someone centuries ago to console himself for a death recorded in that very Bible, or to express gratitude for a birth noted there. Family Bibles are usually rather large, since they were meant to be viewed by several people at once, and often include notes for study. In some instances they’re beautifully illustrated with steel or copper-plate engravings.

If you’re a real connoisseur you might wish to collect English Bibles issued by different publishers. At the time the King James Bible was published only the king’s printer was allowed to print Bibles. Only Oxford and Cambridge were exempted because of their status as institutes of learning. Each publisher had its own distinctive style, and these differences can be fascinating for collectors with an eye for detail.

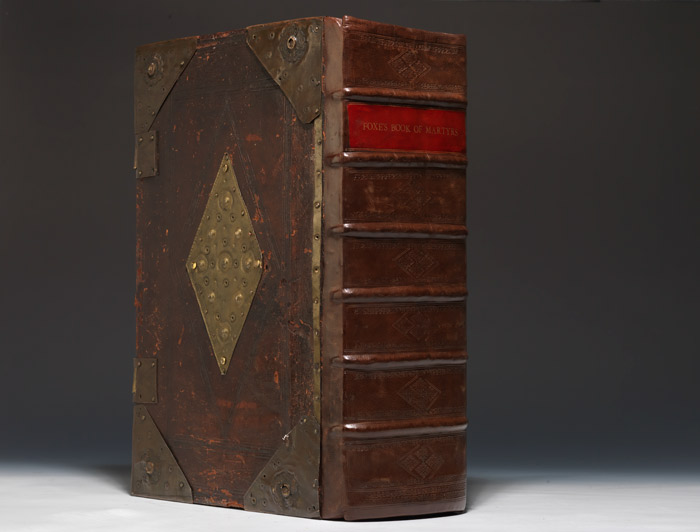

You might also want to branch out into other collecting areas that are closely related to the history of the Bible in English. For example, John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (first published in 1563) records the executions of Tyndale, Rogers, and many other early reformers. Early editions, often sprinkled with woodcuts or engravings depicting emotionally charged scenes of martyrdom, are scarce but acquirable. Early editions of the Book of Common Prayer (first published in 1549) are even more accessible. They’re closely related to the history of the Bible in English in two respects: they contain the liturgy of the Anglican Church, which was the main institutional offshoot of the English Reformation, and they’re printed in English, which, as we have seen, was a core goal of Protestant reformers from the beginning.

To sum it all up, building a collection of English-language Bibles (and closely-related texts) can be a source of manifold satisfactions: the books themselves are of immense religious and historical significance, their history is multi-faceted and surprisingly dramatic, and the fine points are endlessly fascinating.