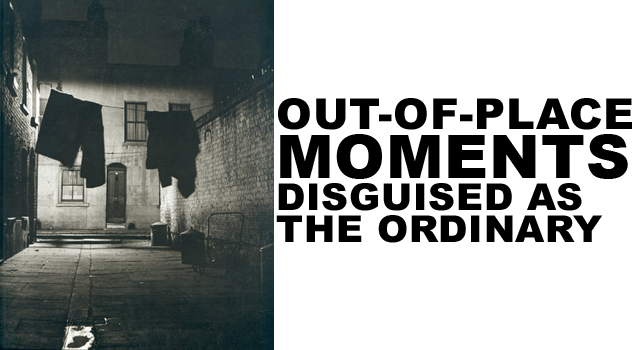

Viewing the images in Bill Brandt’s A Night in London reminds me of Sherlock Holmes. As I turn the pages, I am transported to foggy nights in the capital city, and walks along the river by streetlight—scenes so often portrayed in the black-and-white detective films made during the same era and starring Basil Rathbone as Holmes. Brandt, much like the highly observant literary character, prowled late 1930s London in search of out-of-place moments disguised as the ordinary.

Possessed of an incredible eye for design and composition, Brandt beautifully framed the light creeping through the cracks. He made light purposeful by the buildings and the people he chose to photograph. Elements of the night are picked carefully for their character and their persona.

In many ways, Brandt was parting the heavy black curtain shrouding both photography and a nation on the brink of war to reveal the hidden London. The city that, until then, was for the most part unseen—despite its integral part in the city’s foundations.

Brandt’s documentary style was unusual for the time, as was his choice of subjects. Rigid portraits and regimental set-ups were not for him. It is this departure from the perceived norm that makes him an important British photographer, and rightly so. To see his images is an adventure in time replete with the atmosphere, attitude and emotions of the nation. These are the facets that generations of photojournalists have aspired to ever since.

As James Bone writes in the book’s introduction,

“He can give even the jaded Londoner a thrill with his presentation through the tall railings of the guardsman in his shining helmet as though we were beholding the living London through the bars of its cage. His device too, of revealing a room through the window, the occupants at cards or reading papers or glancing up at the intruder makes one feel a new Asmodeus.”