“In America the law is king,” Thomas Paine declared in Common Sense. The Founding Fathers’ most important and widely-owned law book was William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England.

John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, John Marshall, and John Dickinson all read and owned various editions and frequently cited it in their writings.

The principal aim of society is to protect individuals in the enjoyment of those absolute rights, which were vested in them by the immutable laws of nature… The rights of the people of England… may be reduced to three principal or primary articles; the right of personal security, the right of personal liberty; and the right of private property…

— Blackstone’s Commentaries

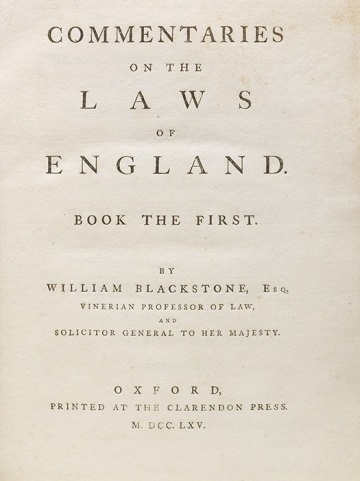

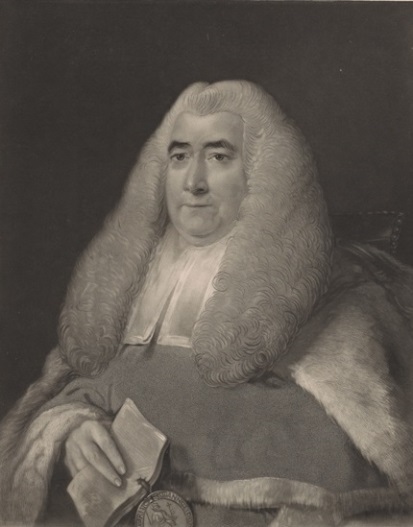

Sir William Blackstone (1723-1780) was a lawyer, law professor, judge, and member of Parliament from 1761 to 1770. A supporter of the Stamp Act and the Crown, his influence on the Founders isn’t as paradoxical as it appears. Wilfrid Prest observed:

Blackstone was no friend to the American Revolution… But Blackstone’s clearly-stated emphasis on the authority of the law of nature and the absolute rights of individuals was of particular importance in formulating and defending the case for armed resistance to King George and his parliament… The Commentaries thus became and remained the basis of US legal education, hence moulding American legal thought and practice throughout the nineteenth century, and beyond.

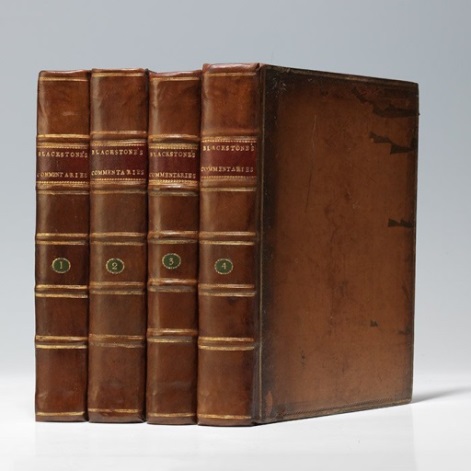

The first edition of Blackstone’s Commentaries was published by Oxford’s Clarendon Press in four quarto volumes from 1765 to 1769, and it was reprinted in numerous editions.

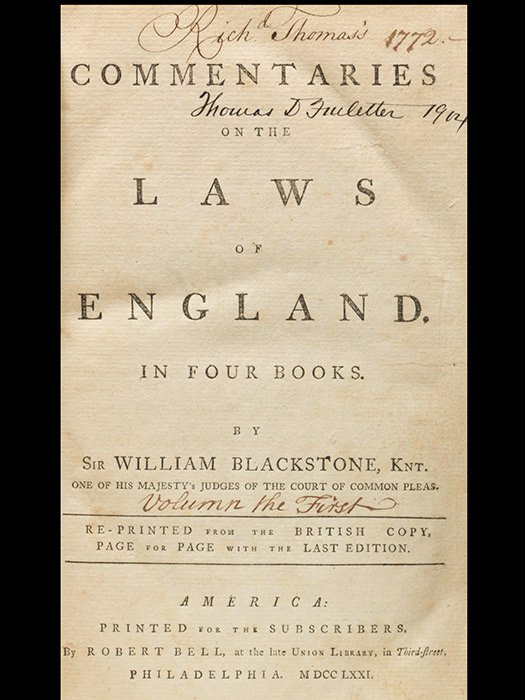

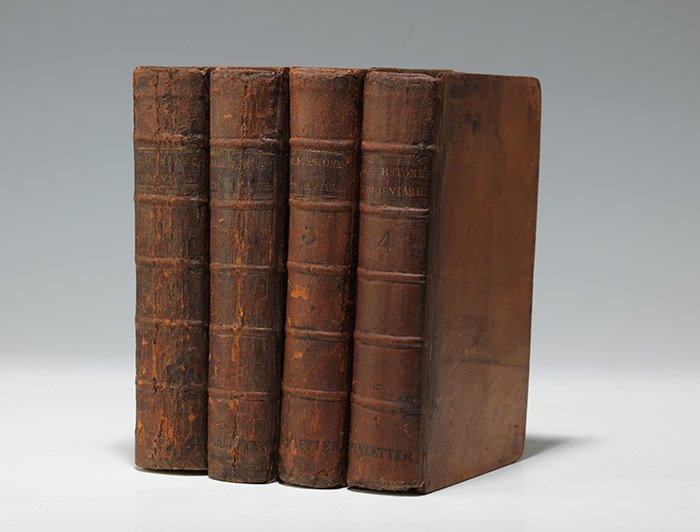

But the edition of the greatest significance to the Founders was the first American edition, published in Philadelphia by Robert Bell in four octavo volumes from 1771 to 1772.

About a thousand British copies had been imported and sold in America in the years before Bell printed his American edition. Published by subscription, nearly 1600 copies of Bell’s edition were ordered. Bell’s prospectus stated that his edition was $8, while the imported British copies were $26. Bell’s edition has a 22-page subscribers list (listing names, cities, and professions), which includes John Adams, John Dickinson, James Wilson, John Jay (later the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court), and Thomas Marshall, who bought it for his teenaged son John Marshall (John read it four times by the age of twenty-seven and became the fourth Chief Justice). Sixteen subscribers became signers of the Declaration of Independence and six became members of the Constitutional Convention, according to David Lockmiller.

James Green noted the success and implications of Bell’s American edition:

He got buyers for his books in every part of North America in a period when few books were sold beyond the province in which they were printed… These books were also enterprising in the sense that they were vigorous, even defiant statements of American independence. They were key texts for those intellectuals who had protested the Stamp Act and organized the nonimportation agreements… These books can also be viewed as declarations of independence from the London book trade.

Blackstone had “the most profound influence on shaping the legal thought of the Revolutionary and Founding generations,” noted William Bader. “All of our formative documents—the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Federalist Papers, and the seminal decisions of the Supreme Court under John Marshall—were drafted by attorneys steeped in Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries,” observed Robert Ferguson.

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson each owned multiple editions of Blackstone, including Bell’s first American edition. Adams’ annotated copies of the 1771 Bell edition and a 1768 Oxford edition are at the Boston Public Library. Jefferson’s signed, incomplete copy of the 1771 Bell edition is at the University of Virginia; the Library of Congress has two other Jefferson copies, a later American edition and an earlier Oxford edition.

In his correspondence, Jefferson frequently recommended the work, calling it “the most elegant & best digested of our law catalogue.” But he also criticized its enormous influence in an 1810 letter: “The opinion seems to be that Blackstone is to us what the Alcoran is to the Mahometans, that every thing which is necessary is in him, & what is not in him is not necessary.”

Blackstone’s Commentaries, unlike other law books of the time, was written in a clear, precise, and elegant style. James Madison mentioned in a 1773 letter that he was reading the work and commented: “I am most pleased with & find but little of that disagreeable dryness I was taught to expect.” Madison included Blackstone in his 1783 list of “books proper for the use of Congress.”

Edmund Burke spoke of Blackstone’s extraordinary popularity in America in his famous 1775 speech in Parliament on conciliation with the colonies, and he cited the colonists’ study of law as a source of the conflict with Britain:

In no country perhaps in the world is the law so general a study… The greater number of the deputies sent to the Congress were lawyers. But all who read (and most do read) endeavor to obtain some smattering in that science. I have been told by an eminent bookseller that in no branch of his business, after tracts of popular devotion, were so many books as those on the law exported to the plantations. The colonists have now fallen into the way of printing them for their own use. I hear that they have sold nearly as many of Blackstone’s Commentaries in America as in England… This study renders men acute, inquisitive, dexterous, prompt in attack, ready in defense, full of resources. In other countries, the people, more simple, and of a less mercurial cast, judge of an ill principle in government only by an actual grievance; here they anticipate the evil, and judge of the pressure of the grievance by the badness of the principle. They augur misgovernment at a distance; and snuff the approach of tyranny in every tainted breeze.

Read my other posts on Books the Founders Read.