Someday, I’d like to play King Arthur in a production of Lerner and Loewe’s Camelot. I long ago memorized all of Arthur’s songs and a lot of his dialogue—including the show’s last scene.

Maybe you know it; it’s a beautiful moment. As Arthur prepares for what will be his last battle, he discovers a boy in hiding, hoping to fight at the king’s side. Arthur knights the boy, but orders him to leave and live a long, full life, telling everyone stories of the Round Table and its quest for honor, justice, and peace. “Don’t let it be forgot,” Arthur sings, “that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment…” The boy, named Tom, runs back home to Warwick to obey his king’s command.

With that moment (taken from its source material, T.H. White’s The Once and Future King), Camelot makes Sir Thomas Malory, of Newbold Revel in Warwickshire, a character in the legends that he, arguably more than any other author, made famous.

Thomas Malory and His “Whole Book” of Arthur

The Arthurian content in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia was mostly military. But through the next three centuries, King Arthur started drawing other kinds of tales into his orbit, in England and abroad. In France, the verse romances of Chrétien de Troyes envisioned Camelot (a place first mentioned by him) as a scene of courtly love. He introduced Lancelot—King Arthur’s greatest knight, Queen Guenevere’s devoted paramour—to the legend’s cast of characters. And in Germany, the singing poet Wolfram von Eschenbach composed Parzival, an epic continuation and conclusion of Chrétien’s unfinished story of the Holy Grail, and a work that may have bolstered the Knights Templar.

Malory didn’t create the Arthurian story we know today—in fact, only one short tale in his book seems to be completely original—but he did craft it, artfully shaping a myriad of stories into one largely continuous and coherent narrative, a “whole book of King Arthur” (as Malory himself called it). The “only true English epic” (Printing and the Mind of Man), Le Morte Darthur established itself as the definitive Arthurian plot for centuries. It remains the chief exemplar of Western literature’s chivalric tradition.

The real Thomas Malory might not have been as endearing or idealistic as his musical theater counterpart. At various times, he faced such allegations as theft, assault, extortion, rape (twice), ambush, even attempted murder. When he died in 1471, he was likely in prison. He never stood trial; we can’t know his guilt or innocence. But when we read his parting words in the Morte, we may sense more in them than false modesty or conventional piety:

I pray you all, gentlemen and gentlewomen, that read this book of Arthur and his knights from the beginning to the ending, pray for me while I am alive that God send me good deliverance, and when I am dead, I pray you all pray for my soul.

Whatever the merits of Malory’s soul, his merits as an author are undeniable. “The words sing off the page,” writes Christina Hardyment; “he wrote particularly well, in a dramatic, colloquial English that everyone could, and still can, enjoy.”

Pioneering English printer William Caxton published Malory’s book in late July 1485, giving this most British book its once and future French title by mistake. Less than a month after it came off the press, it demonstrated the continuing pragmatic appeal of Arthurian legend to those in power. King Henry VII, who won the Wars of the Roses at Bosworth Field, claimed Arthurian lineage; a year later, he named the newborn Prince of Wales “Arthur.”

But if any political agenda motivated Malory, it remains a marginal concern. He loved the legends for their color, their drama, and their high ideals—the same reasons his readers love them, and his recounting of them, more than five centuries later.

Beardsley’s Art Nouveau Challenge to Chivalry

Rare book collectors sometimes speak of “holy grails”—books that are elusive but, in theory, obtainable. Sadly, the first edition of Malory’s Morte is even harder to achieve than the Grail. Not even the most pure-hearted bibliophile can hope to acquire one; only two known copies exist. But you can add other versions of it to your Arthurian library, from handsomely bound modern renderings to elegant, artistic editions important in their own right.

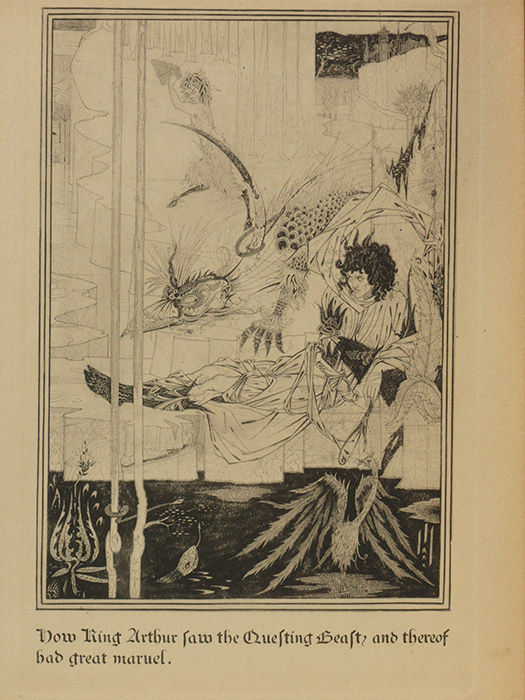

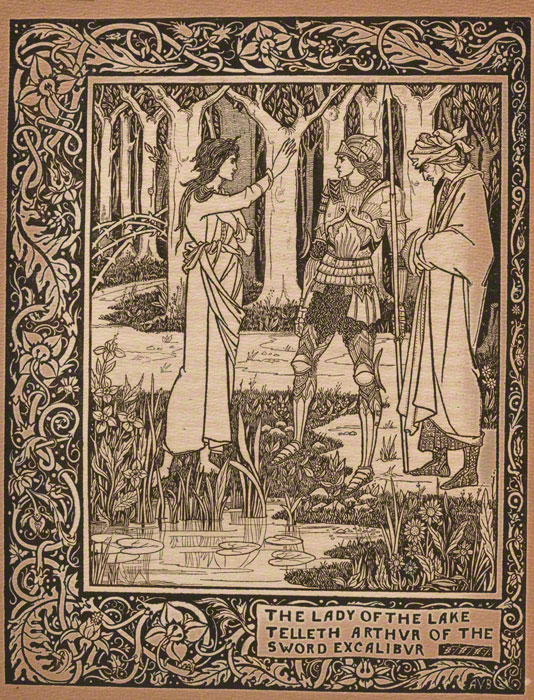

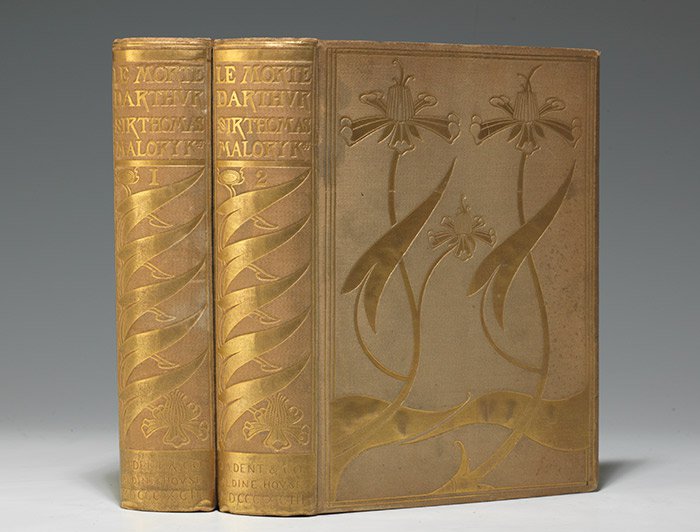

One such edition is the first edition of illustrator Aubrey Beardsley’s first book, The Birth, Life and Acts of King Arthur (a title drawn from Malory’s own). Published in 1893-94 (in monthly parts; later bound as two thick tomes in gilt-decorated cloth, or three in vellum), this edition sallied forth into the marketplace as publisher John M. Dent’s affordable alternative to the sumptuous volumes of William Morris’ Kelmscott Press. It boasts over 400 black-and-white drawings and decorations by Beardsley, barely 20 and largely unknown. This “windfall commission,” explains Simon Houfe, “gave him independence to work wholly as an artist.”

Beardsley envisions Camelot in the Art Nouveau style for which he is renowned. But another sensibility, dark and decadent, informs his illustrations. “The ladies are very lank and often snaky-haired,” complained one contemporary reviewer; “the knights are seldom athletic in appearance, and there is a vast deal of posing.” This critic also dismissed Beardsley’s Merlin as “hideous.”

What that reviewer failed to recognize, or recognized and rejected, was Beardsley’s implicit critique of the same chivalric ideals Malory’s text celebrates. In drawing damsels and knights who, despite elegant curves and elaborate floral motifs, are fading away into nothingness—in shading the Morte with (as our own Embry Clark has noted) “a sinister element… over-sexed satyrs, sneering mouths, looming death”—Beardsley makes the same point with his pictures that Tennyson, in his Idylls of the King, makes with words: overreaching idealism often contains the seeds of its own doom.

Despite (or perhaps because of) the tension between Malory’s text and Beardsley’s pictures, the Dent Morte won the artist instant acclaim. These illustrations endure as the strongest of Beardsley’s too-brief career; he died of tuberculosis four years later.

Triumph and tragedy, horror and hope, are often entangled in Arthurian legend. Perhaps that’s one reason it continues to fascinate us. We recognize those struggles of light and shadow, good and evil, birth and death, as our own.

Malory, Beardsley, and countless other Arthurian storytellers faced those struggles, as well. Their experiences infuse their narrative and visual art, ensuring that Arthur’s plea in Camelot’s last scene is not in vain. We’ll never forget the “one, brief, shining moment” at the heart of Le Morte Darthur—and we’ll go on looking to glimpse it again.

What is your favorite story from the Arthurian legends? Let us know in the comments below!

Comments

2 Responses to “Collecting Camelot: Rare Arthurian Books, Part 2”

Mariana Roberti says: September 6, 2015 at 12:26 pm

¡Genial post! Mi historia favorita de la leyenda artúrica, es la de Tristán e Isolda.

Mike Poteet says: September 25, 2015 at 1:51 am

Mariana, gracias por leer, y por tu comentario. La historia de Tristan es otro buen ejemplo de las tradiciones que se inició de forma independiente del rey Arturo , pero encontró su camino a Camelot en el final. Una vez Malory utiliza Tristan y Isolda en paralelo Lancelot y Guinevere , creo que los dos cuentos se hicieron inseparables . ¿Tiene una versión favorita de la leyenda de Tristán?

(Mariana, thank you for reading, and for your comment! The Tristan story is another good example of traditions that began independently of King Arthur, but found their way to Camelot in the end. Once Malory used Tristan and Isolde’s story to parallel Lancelot and Guenevere’s, I think the two tales became inseparable. Do you have a favorite version of the Tristan legend?)