During the Golden Age of science fiction (or “sf”), the genre set it sights on exploring starry frontiers and seemingly infinitely expanding futures. But when the atomic bomb brought World War II to an end, many people sensed science fiction had become science fact in a dramatic, even disturbing way.

Spaceships screaming across alien skies wouldn’t entirely vanish from sf. But authors in the postwar years and beyond increasingly took extraordinary voyages into the human heart and soul. Even as the Space Race began, science fiction writers and readers—who’d been going to and from the Moon for decades—started charting courses toward inner space.

Heinlein’s “Martian Mowgli”

By the late 1950s, Robert Heinlein was unhappy with his reputation as a writer of boys’ books. Today, his classic “juveniles” such as Have Spacesuit—Will Travel and Rocket Ship Galileo (inspiration for the classic 1950 movie Destination Moon), while dated, can still stoke readers’ sense of wonder; they’re a fondly remembered part of Heinlein’s legacy. As the Golden Age dimmed, however, Heinlein was determined to do something different. “I would like to find out,” he wrote to a friend, “if I can write about adult matters for adults, and get such writing published.”

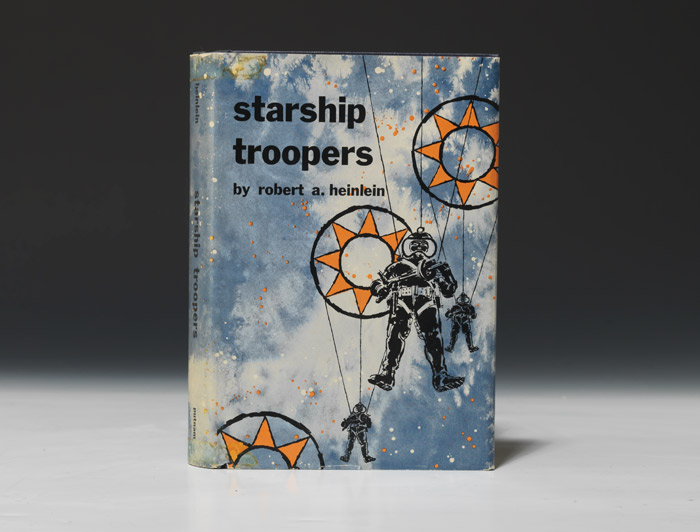

He came close with Starship Troopers (1959). Heinlein had intended the book to be another “juvenile.” But the story of Johnny Rico’s coming-of-age as an interstellar infantryman startled Scribner’s, Heinlein’s publisher. The book’s violence and robustly expressed political and social opinions set it apart from Heinlein’s previous books, and unsettled Scribner’s enough that they rejected it. Undeterred, Heinlein sought another publisher. Eventually published by Putnam’s, Starship Troopers raised Heinlein’s profile even higher, and garnered him his second Hugo Award.

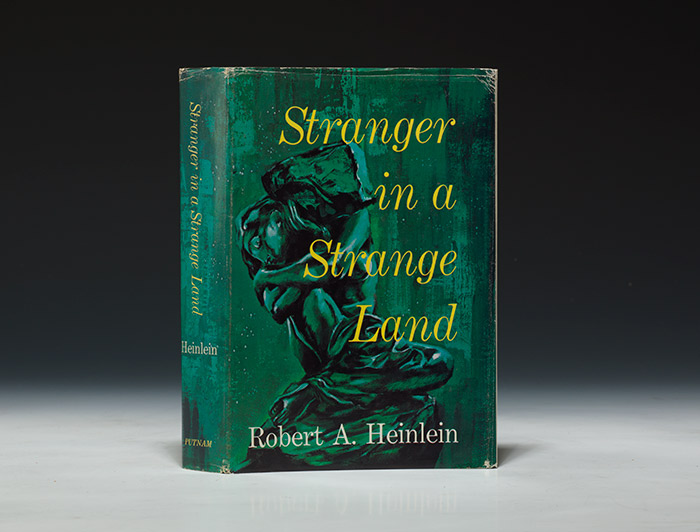

Heinlein finally achieved the “adult” vindication he sought with his next, most famous novel. His wife Virginia had planted the story’s seed back in 1948: a “Martian Mowgli” tale about an orphaned human child raised, not by wolves, but by extraterrestrials. Stranger in a Strange Land (1960) electrified the public. Mystical, satirical, filled with images of communal living and free love—even in its abridged form (the complete text wouldn’t see print until 1991), the book attracted enormous attention. It was the first sf book to become a New York Times bestseller.

Stranger found some of its most enthusiastic fans in the nascent counterculture. It became one of the movement’s key texts; its concepts and language—most notably grokking, the intimate merging of identities—entered the decade’s consciousness. The book also garnered notoriety when news reports wrongly identified it as one of Charles Manson’s inspirations (some of his “family” read it, but not Manson himself).

Despite its protagonist’s Martian upbringing—and despite the fact that it won Heinlein his third Hugo Award—Heinlein never considered Stranger to be science fiction. It was, for him, another of his pleas for people to think for themselves. Naturally he objected when people suggested he could build a religion around his phenomenally popular book. “I don’t offer a solution,” he would say of Stranger, “because there isn’t one… [The mantra] ‘Thou art God’ that runs throughout… is not offered as a creed but as an existentialist assumption of personal responsibility, devoid of all godding.”

Ender’s Game and the Golden Age Reconsidered

Science fiction continued to mature, but its authors never forgot the Golden Age. Instead of looking backward with nostalgia, however, some writers began reassessing its tropes and themes, using them to ask new questions about the nature and destiny of humanity.

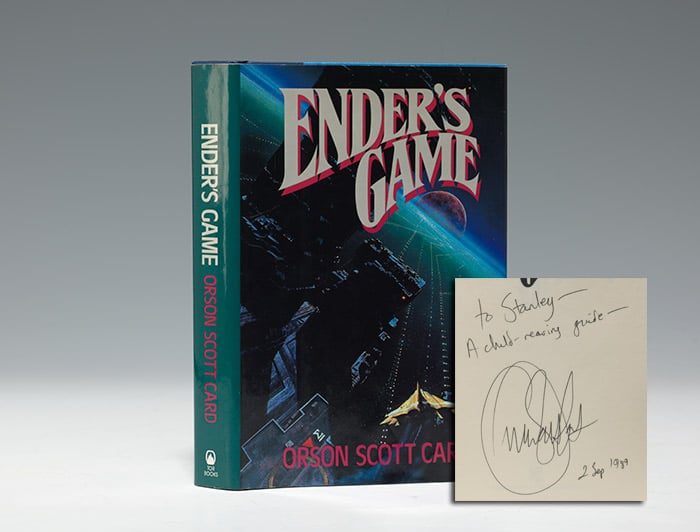

In some ways, for example, Orson Scott Card’s widely acclaimed, award-winning novel Ender’s Game (1985, an expanded version of Card’s 1977 short story of the same name) mines the same vein of space-based military action-adventure Heinlein mined for Starship Troopers. Card’s space cadets, however, are not young adults, but children. Earth’s military chooses them to attend an orbital Battle School where they endure rigorous training to fight insect-like aliens very reminiscent of the “Bugs” Johnny Rico and his squad went up against.

Card has denied having made any conscious effort to answer Heinlein. And certainly, Ender’s Game offers a far more sobering perspective on military service and warfare. It weighs the exorbitant mental and spiritual costs of violence, to individuals and society, and questions the assumptions behind war in way Starship Troopers did not. The conclusion of Ender’s Game is emotionally devastating; they are bleak but beautiful chapters, haunting readers with the fragility of hope and the urgent necessity of communicating with and attempting to understand “the other,” whether extraterrestrial life forms or the people alongside us who can sometimes seem every bit as “alien.”

Ender’s Game remains Card’s best-known work, and an important touchstone of modern sf. It frequently appears on school reading lists (one of those rare assigned texts students don’t end up resenting). It has helped inspire real-life research into the military applications of virtual reality. Most of all, it has become a classic because of Card’s literary artistry and compelling themes. “What works with Ender’s Game,” Card once said, “is Ender’s community-building… I certainly was not conscious of it as I was writing him… yet I created the kind of guy that I would follow.”

(Read about our fine, inscribed copy of this science fiction classic.)

Click here to read our first post in Collecting Rare Science Fiction: Genesis of a Genre.

Click here to read our second post in Collecting Rare Science Fiction: The Golden Age.

What’s your favorite modern work of science fiction?