I’ve always had a hazy kind of affection for Edgar Allan Poe. His stories are strange and rich; his poems are satisfyingly moody. (He was also my middle school’s namesake – go Ravens!) In the canon of American literature, though, Poe cuts a more protean figure, as equally beloved as he is derided.

In his day, he was respected (or at least feared) as a critic, but as a writer he was every critic’s favorite whipping boy. In life he struggled to feed himself, but in death he’s universally acknowledged as the father of a somewhat obscure literary genre called detective fiction – maybe you’ve heard of it? Arthur Conan Doyle calls Poe’s stories “a model for all time,” while Ralph Waldo Emerson summarily dismissed “The Raven” in a single sentence: “I can see nothing in it.”

It’s not hard to understand why Poe’s writing draws such strong reactions. His work couples the melodramatics of a surly teenager with the unyielding grief you might expect in the lone survivor of a car wreck. Indeed, in a CNN interview given last year, John Cusack (yes – that John Cusack) talked about Poe as representing “some sort of collective sorrow.”

In his 1829* poem “Alone,” Poe writes:

From childhood’s hour I have not been

As others were – I have not seen

As others saw – I could not bring

My passions from a common spring –

From the same source I have not taken

My sorrow – I could not awaken

My heart to joy at the same tone –

And all I lov’d – I lov’d alone –

Somewhere in there, I think, is the seed of his continued popularity. The poem twines together inextricably both the surliness and the grief into something altogether recognizable: a kindred spirit.

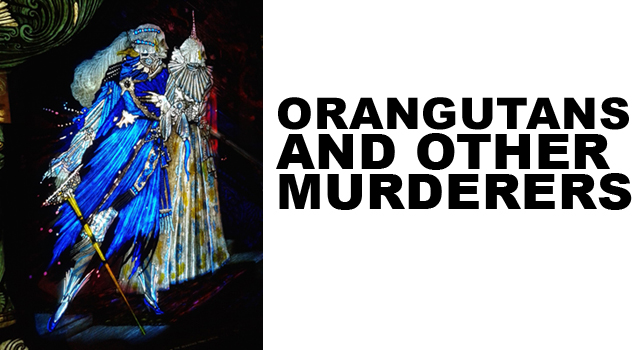

In any case, one thing remains clear: Poe’s writing lends itself easily to visual interpretation. Some of the greatest illustrators from the 19th and 20th centuries produced excellent editions of Poe’s work – Arthur Rackham, Edmund Dulac, Gustave Dore. The very best of them though is Harry Clarke.

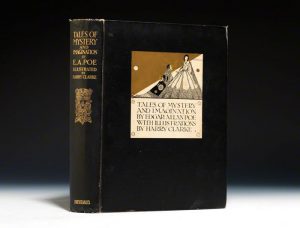

When it was first published in 1919, Clarke’s edition of Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination featured 24 full-page black-and-white illustrations, as well as a handful of vignettes. In 1923, another edition was published with an additional 8 full-page color plates.

A prominent figure in the Irish Arts & Crafts Movement, Clarke was greatly influenced by Art Noveau in general and Aubrey Beardsley in particular.

The Irishman’s illustrations so strongly match the baroque detail and gothic tone, the macabre humor and straight up creep factor of Poe’s writing, that it’s easy to imagine the artwork generated the stories, rather than the other way around.

Over the course of his career, Clarke published editions of other literary works – most notably Goethe’s Faust and Andersen’s Fairy Tales – but his primary artistic vocation was not book illustration. It was stained glass. And by any standard, he was a master.

*Although it was composed in 1829, “Alone” wasn’t published until 1875, more than 25 years after Poe’s death.

Comments

2 Responses to “E.A. Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination, illustrated by Harry Clarke”

Jaq says: June 26, 2013 at 5:04 pm

Wonderful post. And what amazing illustrations! Thank you for… illuminating… them for us 🙂

PS: Cusack starred as Poe in last year’s “The Raven.” Might be why he had thoughts on the man.

Embry Clark says: July 2, 2013 at 7:25 pm

Thanks, Jaq! I’m glad you enjoyed the post – Clarke’s definitely a favorite of mine.