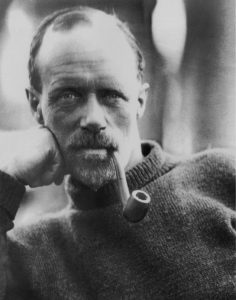

By most reasonable standards, the actions of Ernest Shackleton and his crew during the Endurance expedition (1914-1917) can only be categorized as heroic. Indeed, given the string of calamities that battered the expedition, their mere survival bespeaks superior leadership, unending resourcefulness, and sheer force of will. But instead of parades and champagne, they returned to a country deeply entrenched in the Great War, which by then had claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of Britons.

Although age and a weakened heart kept Shackleton from military service, he was nevertheless determined to contribute in whatever way he could. There was an ill-fated attempt at Allied diplomacy in Argentina and Chile, as well as an undercover spy-like mission to Spitsbergen in Norway (where the Germans had a meteorological station), and after Armistice, a financial scheme to develop Northern Russia. Shackleton was thwarted at every turn – first by a heart attack (en route to Spitsbergen) and then by the Russian Revolution.

After the war, he languished on the lecture circuit, attempted to repay debts by publishing South, drank too much, and ignored his ever-worsening heart disease. There’s a sense that Shackleton believed he was only at his best when there was “winter sledging with a fight at the end,” and so in 1920, his plans turned once again to Antarctica.

(Bonus fact: Shackleton initially planned for a northern – i.e. Arctic – expedition, but those plans ultimately unraveled because of policy changes in the Canadian government.)

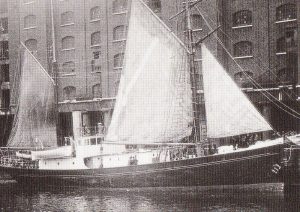

The goals of the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition (1921-1922) – the so-called Quest expedition, after its ship – were decidedly amorphous. The plan was apparently to circumnavigate the Antarctic continent by sea and to chart all of the smaller, largely unexplored Antarctic islands. So it was that in September 1921, after an inspection by the King, the Quest set sail among much fanfare.

(Bonus fact: The Quest was financed by John Quiller Rowett, an old school friend of Shackleton’s. Rowett put up £70,000. In today’s pounds, that comes in at just over £2.25 million.)

It will surprise you not at all to learn that things went wrong almost immediately. The ship handled poorly, burned fuel too quickly, and leaked constantly. She required repairs at nearly every port of call. The real disaster was yet to come, however.

Shackleton’s ill health was, by now, obvious to everyone. In December 1921, he suffered a heart attack aboard ship – his second in three years – which he ignored. He was drinking heavily (presumably as pain management) and refusing to rest. In January 1922, when the ship’s physician, Alexander Macklin, urged Shackleton to “take things easier in the future,” he replied: “You are always wanting me to give up something, what do you want me to give up now?” Several minutes later, he had a third heart attack and died. He was 47. He was buried shortly after – at Emily Shackleton’s request – on South Georgia.

After Shackleton’s death, Frank Wild, his longtime second-in-command, assumed control of the Quest and completed the ship’s journey. He battled the ice pack and the weather in order to sail along the coast and even managed (after a few failed attempts) to visit Elephant Island again.

(Bonus fact: During the Endurance expedition, it was Wild who held everyone together on Elephant Island after Shackleton set out to reach South Georgia. Wild’s belief in Shackleton was undying, and each time the ice floes cleared, he instructed the rest of the crew: “Roll up your sleeping-bags, boys: the Boss may be coming today.”)

In 1923, Wild published Shackleton’s Last Voyage, an account of the expedition, which he supplemented with excerpts from Shackleton’s own diary.

The Quest expedition is acknowledged by most as the end of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. In the decades following his death, however, Shackleton’s legacy was largely obscured by the sad fate of Captain Robert F. Scott and his Terra Nova expedition. (I’ll tell you all about it in a future post.) It wasn’t until the late 1950s that people really began to pay attention to Shackleton – due in equal measure to the appearance of several new biographies and to the slow (and decidedly controversial) dismantling of Captain Scott’s standing as The Great National Hero.

Shackleton’s legacy is one of leadership and perseverance in one of the most harrowing climes on the planet. It seems fitting, therefore, to close with the words of two men who understood intimately the exacting magnitude of Shackleton’s accomplishments.

Cherry Apsley-Garrard, British zoologist and member of Scott’s Terra Nova expedition:

Do not let it be said that Shackleton has failed… No man fails who sets an example of high courage, of unbroken resolution, of unshrinking endurance. […] There is an impression of the right thing being done without fuss or panic. I know why it is that every man who has served under Shackleton swears by him.

Sir Raymond Priestley, British geologist and member of Shackleton’s Nimrod and Scott’s Terra Nova expeditions:

[W]hen you are in a hopeless situation, when there seems to be no way out, get on your knees and pray for Shackleton.