George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton… These are the big six, the famous names we immediately think of as America’s Founding Fathers. They were indeed extraordinary, but there were many others who made important contributions to the founding of America.

In this series of posts, I’ll introduce you to the writings of some of the “Forgotten Founders” who have faded from history, or whose achievements were obscured by controversy, or who simply aren’t usually ranked among the great Founders but deserve greater recognition.

Let’s begin with George Mason, the most important Virginian you’ve probably never heard of, a man praised by Jefferson as “the wisest man of his generation” and by Madison as “a powerful reasoner, a profound statesman, and a devoted republican.”

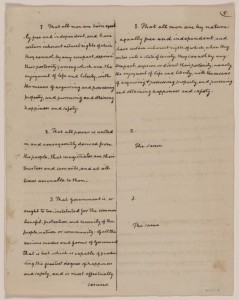

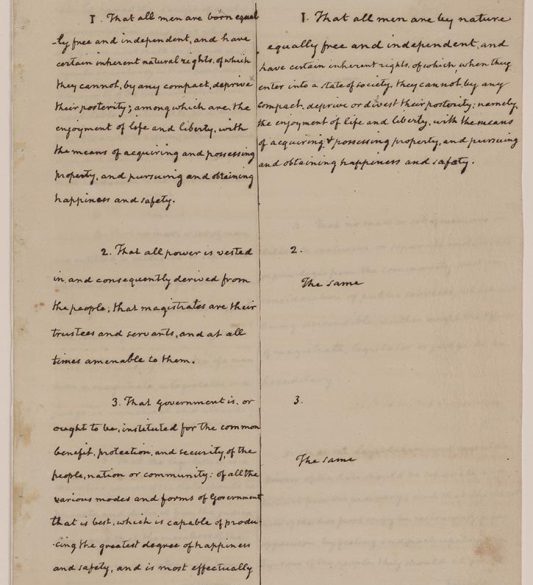

That all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain inherent natural rights’; among which are, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

That quote may seem familiar, but it’s not from Jefferson’s July 1776 Declaration of Independence… it’s from George Mason’s May 1776 draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights. This is no coincidence, as Jefferson used Mason’s document when writing his. “Nothing influenced Jefferson more than the draft of Virginia’ Declaration of Rights,” wrote historian John Ferling.

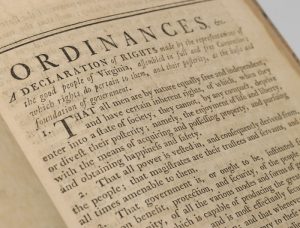

In fact, Mason was the principal author of two of America’s most influential documents’ the Virginia Declaration of Rights (the first American bill of rights) and the Virginia Constitution (the first permanent state constitution, and Virginia’s first constitution). Adopted in June 1776 by the Virginia Convention, they were the basis of our critical founding documents… the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights, and the constitutions and bills of rights of many states, including Pennsylvania and Massachusetts.

Many of the rights protected by the U.S. Bill of Rights were first constitutionally guaranteed in the Virginia Declaration of Rights, including free exercise of religion, freedom of the press, due process, trial by jury, and protections against searches and seizures and cruel and unusual punishment.

In May 1776 the Continental Congress in Philadelphia recommended that each colony create new governments “under the authority of the people”… not the king… for “the defence of their lives, liberties, and properties.” Virginia was the first state to do so. On May 15th, the Virginia Convention approved two historic resolutions: one instructing Virginia’s delegates in Congress to propose independence, and the other to prepare a “Declaration of Rights” and “a plan of government.”

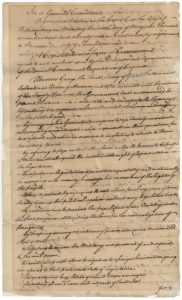

A drafting committee was appointed, but George Mason was the primary author and architect of both documents. As historian Robert Rutland noted, “no man knew more about colonial charters or what the law books said about rights and proper constitutions.” Other members of the committee, including James Madison, made important contributions, but Edmund Randolph noted that Mason took the lead and his drafts “swallowed up all the rest, by fixing the grounds and plan.”

Mason’s first draft of the Declaration of Rights had ten points he considered “the Basis and Foundation of Government.” The drafting committee met on May 24th, accepted Mason’s draft with only a few small changes, and added eight additional articles, five of which were contributed by Mason. This committee draft of the Declaration of Rights (with 18 articles) was reported to the convention on May 27th and debated and revised. The final version (with 16 articles) was adopted by the convention on June 12th. You can read the three versions of the Declaration of Rights on the website of George Mason’s Gunston Hall.

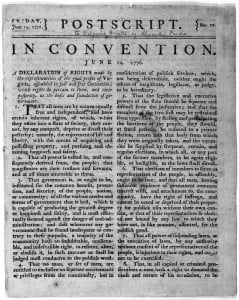

The committee draft of the Declaration of Rights was quickly and widely circulated throughout the colonies in letters, newspapers, and a broadside printed for the Virginia Convention (only one copy has survived). The earliest newspaper appearances were in the June 1st Virginia Gazette and the June 6th Pennsylvania Evening Post. Julian Boyd, the editor of the Papers of Thomas Jefferson, noted that “a primary influence in the drafting of the Declaration [of Independence] is George Mason’s Declaration of Rights, which Jefferson saw in the Pennsylvania Evening Post for June 6.” On June 7th, Virginia’s resolution on independence was introduced in Congress, and on June 11th the drafting committee for the Declaration of Independence was appointed.

On June 10th, Mason’s draft of the constitution became the Virginia committee’s working draft, and it was debated and revised over the next two weeks. Jefferson had been working on his own version in Philadelphia, but the copy he sent to Virginia didn’t arrive until June 23rd, by which time the drafting committee was nearly finished. The committee did add Jefferson’s preamble listing British abuses, which Jefferson “recycled” into the charges against the king in the Declaration of Independence. The committee completed its work on June 24th and reported to the convention, which debated and made additional changes. The final version of the Virginia Constitution was adopted on June 29th, creating a government of executive, legislative, and judiciary branches, with a bicameral legislature.

The final versions of the Declaration of Rights and the Virginia Constitution were printed in newspapers and in the exceptionally rare official Proceedings and Ordinances of the Fifth Virginia Convention, published by Alexander Purdie in July 1776.

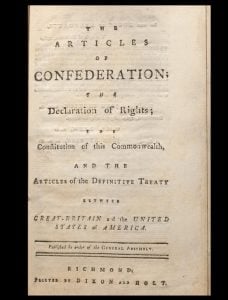

In 1784, the Virginia Assembly ordered that the Virginia Declaration of Rights and Constitution be printed with the ratified Articles of Confederation and the Treaty of Paris and be distributed throughout the state so it may be “accessible to all who may think proper to consult them.”

Mason’s role in history didn’t end in 1776…without him the U.S. Constitution might not have a Bill of Rights. Read all about it in Part 2.

Comments

4 Responses to “Forgotten Founders: George Mason, Part 1- 1776”

Dirk Smit says: June 4, 2014 at 8:24 pm

Hello:

I would expect a blog and other writings from Bauman books to be perfect in all aspects of the English language.

The first sentence of your fifth paragraph demonstrates incorrect usage of the word “principle”. The correct spelling in this case is “principal”. Otherwise, an interesting article.

Rebecca Romney says: June 19, 2014 at 1:07 am

You are right. An unfortunate error we somehow overlooked. Thank you for pointing that out.

Jon Roland says: June 13, 2015 at 1:38 am

Can anyone provide a complete list of all the delegates to the Fifth Virginia Convention of 1776?

David E. Young says: January 14, 2018 at 11:44 am

George Mason is The Giant of American Constitutionalism, the foundations of which are located within his papers.