Before the battle of Trenton the half-clad, disheartened soldiers of Washington were called together in groups to listen to that thrilling exhortation… The literary musket reaches its mark… The great commander… presently saw his dispirited soldiers beaming with hope, and bounding to the onset, —their watchword: These are the times that try men’s souls! Trenton was won, the Hessians captured, and a New Year broke for America on the morrow of that Christmas Day, 1776.

— Moncure Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine’s The American Crisis is a series of thirteen essays separately written and published between December 1776 and April 1783, from “the very blackest of times” to the end of the Revolutionary War.

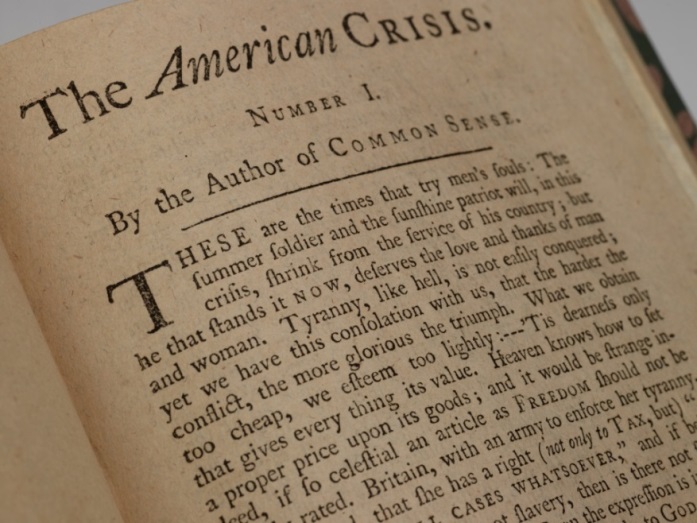

Paine wrote the famous opening lines of Number I as the Continental Army was facing defeat, and Washington ordered it read to his troops on December 23rd before the crossing of the Delaware and the Christmas attack that changed the course of the war:

These are the times that try men’s souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly.

America had declared independence, but the war still had to be won to make it a reality. In the fall of 1776, after the British captured New York City, Paine volunteered for Washington’s Continental Army and served as aide-de-camp to General Nathanael Greene, commander of Forts Lee and Washington on the Hudson River. Paine wrote accounts of the battles for Philadelphia newspapers and may have been America’s first war correspondent.

Washington’s army suffered a series of major defeats, and in mid-December they retreated to the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River. Only a few thousand soldiers remained, and many enlistment contracts would expire by the end of the year. Washington wrote that without more troops, “I think the game will be pretty well up.” The Continental Congress fled Philadelphia on December 12th after Washington warned that the city was in danger. “It looked as if the fledgling United States was doomed,” remarked Harvey Kaye.

Officers told Paine that “the country needed him writing more than fighting. Paine agreed and walked thirty-five miles to Philadelphia, expecting to be captured at any moment during the eleven-hour trek. British forces knew all too well who ‘Common Sense’ was. Paine arrived to find Philadelphia in chaos,” Craig Nelson wrote.

Paine later recalled:

Seeing the deplorable and melancholy condition the people were in, afraid to speak and almost to think, the public presses stopped, and nothing in circulation but fears and falsehoods, I sat down, and in what I may call a passion of patriotism, wrote the first number of the ‘Crisis.’ It was published on the nineteenth of December, which was the very blackest of times… I gave that piece to the printer gratis, and confined him to the price of two coppers, which was sufficient to defray his charge.

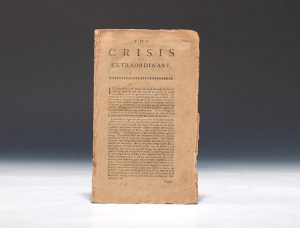

Number I was published in Philadelphia by Styner and Cist as an eight-page pamphlet on December 19, 1776. (Many sources incorrectly state that it was printed on that date in the Pennsylvania Journal, but that newspaper suspended publication in late November 1776 and didn’t resume until late January 1777.) It was reprinted in newspapers throughout the country.

Paine “knew just what Americans needed to hear in that time of terror and invasion… As with Common Sense, he rallied his countrymen, evoking the Revolution as a cause far greater than any disagreement over tariffs. With his first Crisis, he ennobled each and every citizen rebel into a heroic agent of destiny, and of history,” Nelson noted.

Paine’s essay “recharged the revolutionary cause,” Kaye wrote, and “enabled Washington to turn the tide of battle, for the Crisis served both to recruit militiamen back to their units and to persuade locals to volunteer aid and assistance.”

My pen and my soul have ever gone together. My writings I have always given away, reserving only the expense of printing and paper, and sometimes not even that. I never courted either fame or interest… A lasting independent peace is my wish, end and aim.

— Number II

But Paine had just begun. “At every critical point during the war a new article came from his pen, written in language the plain people in the Continental Army and on the home front could understand, to bolster the Patriot forces, to explain the reasons for defeat and to rally the Americans for the next battle,” wrote Philip Foner.

Paine issued Number XIII, The Last Crisis, on April 19, 1783—the eighth anniversary of Lexington and Concord, only days after Congress officially declared the end of the Revolutionary War. He began by echoing the words he first wrote nearly seven years earlier:

The times that tried men’s souls are over—and the greatest and completest revolution the world ever knew, gloriously and happily accomplished.

Publication History of The American Crisis

Here’s a list of The American Crisis essays and their month and year of publication. I’ve noted those first issued as pamphlets, all of which are exceptionally rare. The rest were given directly to newspapers for publication (most were first printed in Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet).

- Number I— December 1776 (pamphlet, Philadelphia: Styner and Cist; two issues, without and with December 19, 1776 date on the last page). Reprinted in newspapers, as a pamphlet in a few cities, and as a broadside in Boston.

- Number II— January 1777 (pamphlet, Philadelphia: Styner and Cist)

- Number III— April 1777 (pamphlet, Philadelphia: Styner and Cist)

- Number IV— September 1777 (pamphlet, Philadelphia: Styner and Cist)

- Number V— March 1778 (pamphlet, Lancaster: John Dunlap)

- Number VI— October 1778

- Number VII— November 1778

- Number VIII— February 1780

- Number IX— June 1780

- [Number X] The Crisis Extraordinary— October 1780 (pamphlet, Philadelphia: William Harris)

- Number XI— May 1782

- [Number XII] To the Earl of Shelburne— October 1782

- Number XIII, The Last Crisis— April 1783

There’s some disagreement over what comprises the complete work, as Paine didn’t assign the Numbers X and XII, and he wrote additional pieces that some call “supernumerary” Crisis essays.

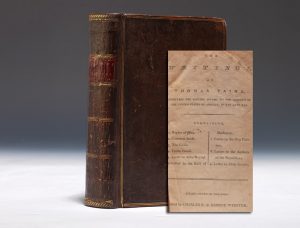

It wasn’t until 1792 that The American Crisis essays were printed together in America, when Albany printers Charles and George Webster published 12 of them in a pamphlet that was also part of their editions of Paine’s collected writings.

You can read my previous Paine posts here: Part 1 is on the controversy over whether Paine was a Founding Father, and Part 2 is on Common Sense.

Comments

2 Responses to “Forgotten Founders: Thomas Paine, Part 3”

Linda Cree says: May 20, 2022 at 11:27 am

Thank you for your informative blog. The more I learn about Thomas Paine, the more questions I have. Why wasn’t he involved in the drafting of our Constitution? Surely he would have cared passionately about it. Was he used when needed, then made unwelcome in the “inner circle” of Founding Fathers when his ideas and persuasive talents would be inconvenient? (Imagine how different our history would be if his advocacy of black and women’s rights had been taken seriously!) John Adams’ hatred of Paine is telling. And why didn’t Washington use his considerable power to get him out of prison in France instead of allowing him to languish there in poor health and constant danger of execution?

Jeff Harman says: July 26, 2022 at 4:04 pm

Thank you for researching and printing the many accolades to Thomas Paine, the most forgotten Founding Father.