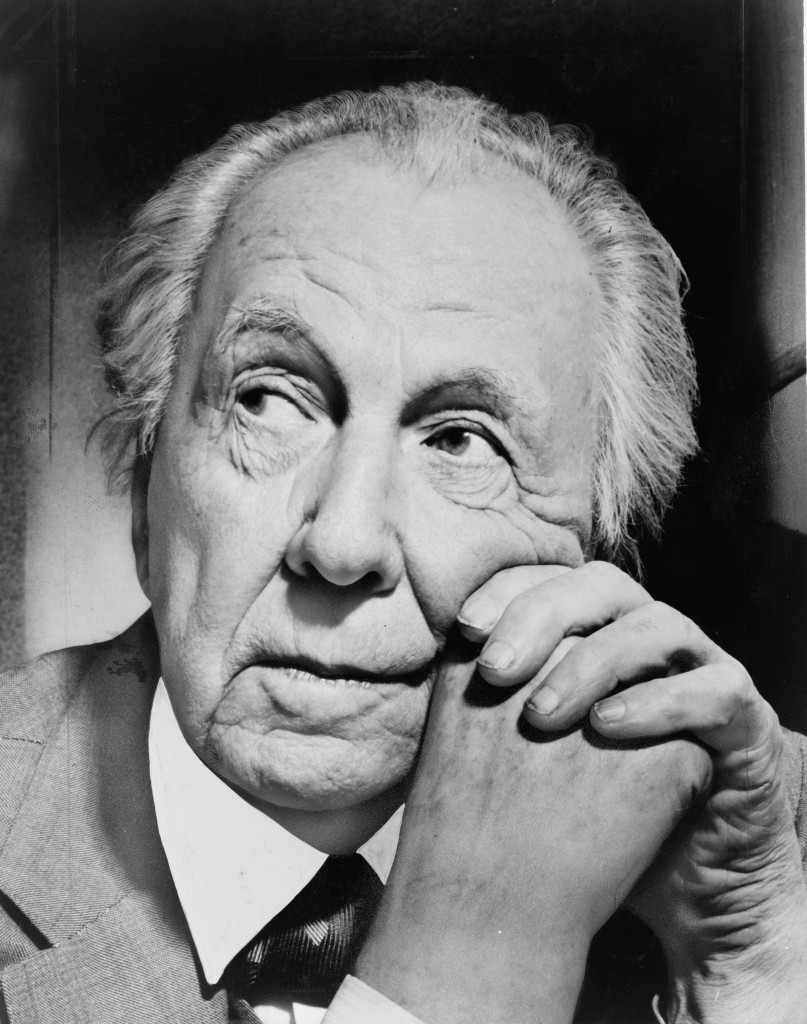

Genius bordering on maniacal attention to detail defines the seventy-year career of the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. A master of all of the tools at his disposal, Wright frequently fused together naturally occurring elements with man-made design to yield spectacular results.

“Ahead of its time,” “Breakthrough” and “groundbreaking” are all phrases used time and again when describing his work. And rightly so, both his designs and innovative solutions to engineering and construction problems of the day were from the future.

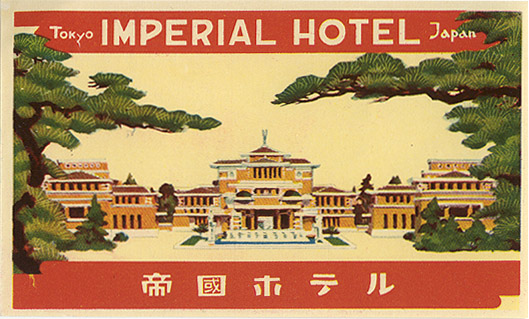

[The image above by David Levine (www.travelbrochuregraphics.com) ]

Best known for the long and low-slung roofs of the “prairie” house, Wright spent his lifetime devoted to architecture in one way or another. If he was not building, he was teaching students how his “organic” work could elevate a landscape and benefit the American people.

All of the working parts available to him from the materials used, the colors of the surrounding landscape, the function and art of the interior and even the choice of furniture were vital to the success of a project. He took his cue from the scale, geometry and layout of the land, and his successes have landed him numerous accolades including the greatest American architect of all time. To date 25 projects have been designated National Historic Landmarks, and 11 are considered most valuable by the World Heritage Convention.

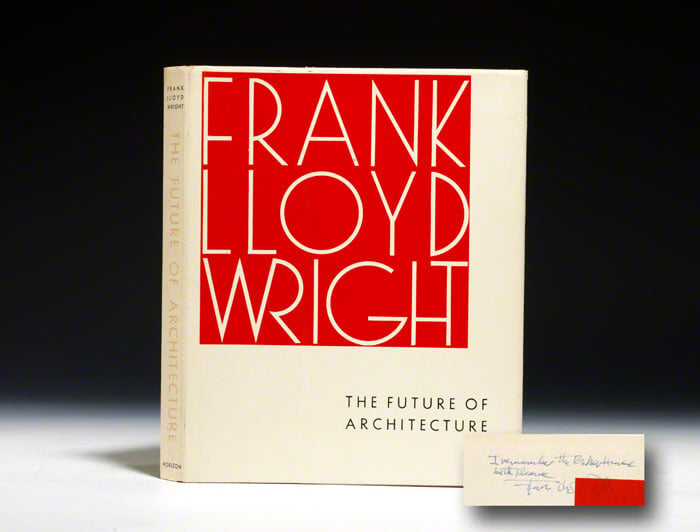

Despite all of this praise, Wright’s career took many ups and downs. In the periods when few commissions were available, he turned to writing, and his first major publication in English – Modern Architecture – was released in 1931. By the time this publication appeared, Wright had already designed many of the buildings with which he is most often associated, including the Unity Temple (1906), Taliesin (1912) and the Imperial Hotel (1923).

Modern Architecture was comprised of Wright’s 1930 Kahn Lectures, which he first presented at Princeton University. This was the first time he attempted to explain in book form his vision, including what he called “the destruction of the box.”

Wright believed a fundamental flaw in architecture, which had gone unchallenged for decades, was that the room was essentially a box formed of corners and walls, ceilings and floors. He decided to take away the corners to allow rooms to jut into one another. In doing so, rooms, and in effect space, was no longer defined by fixed values, but rather relative ones as experienced by the inhabitants. He made more open living spaces by increasing the viewer’s perception of depth while maintaining privacy. In doing so he created psychologically more healthy spaces in which to live. He didn’t just knock down walls to make “open spaces” as is the idea commonly employed today.

A doctor can bury his mistakes, but an architect can only advise his clients to plant vines.

-Frank Lloyd Wright

For a more comprehensive list of Wright’s work, which are open to the public, visit http://www.franklloydwright.org/about/public-sites.html

Comments

2 Responses to “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Destruction of The Box”

Celeste Davison says: September 13, 2020 at 7:29 am

Hello, we have a collection of Frank Lloyd Wright

books and are looking for someone interested in that collection. 250 volumes, several first editions- only one signed by Mr. Wright!

Jessa Feiler says: May 19, 2021 at 6:45 am

Hi Celeste! I’m afraid we were doing internet work during COVID and this comment got misplaced. If you are still interested in selling your collection, we have a link with information about how to offer it to us: https://www.baumanrarebooks.com/selling-something.aspx Thanks for reading!