That great poets imitate and improve, whereas small ones steal and spoil.

When W. H. Davenport Adams wrote positively about the poet Tennyson in his article “Imitators and Plagiarists” in 1892, little could he know that his turn of phrase would itself become the source of inspiration for other great thinkers years later.

And just as T.S. Eliot, William Faulkner and Steve Jobs would be credited with phrases that while not outwardly the same as Adams, shared at least the same DNA, so countless artists have unsurprisingly borrowed, imitated even stolen in literature and the arts for longer than any of us can remember.

For this particular train of thought, let’s begin with the ancient works created by the poet Virgil and the philosopher Cicero. Both were so masterful with language that they greatly influenced the work of generations of writers to come. Perhaps most notably the Italian scholar Francesco Petrarch, who in turn can be credited with inspiring his friend and author Giovanni Boccaccio, who is most responsible for influencing Chaucer.

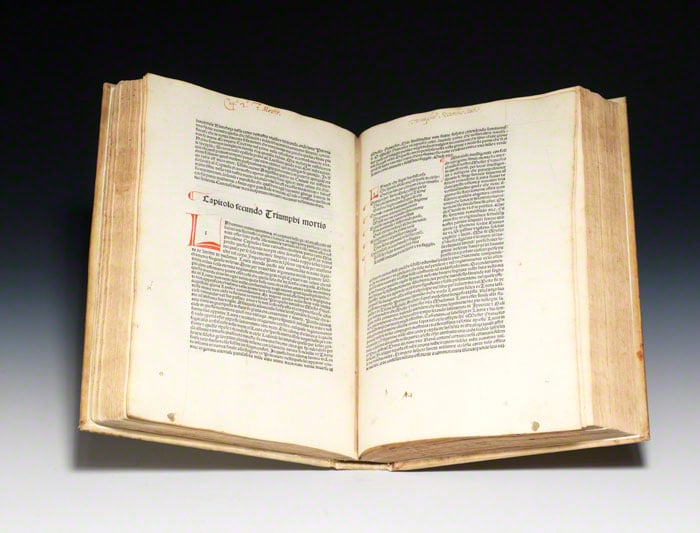

[Image above: An incunable edition of Petrarch’s Trionfi, 1478 (BRB. Petrarch was crowned poet laureate of Rome in 1341.]

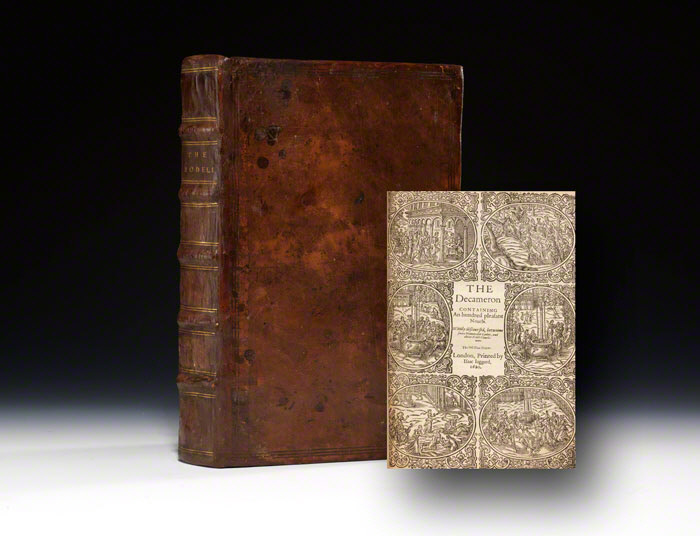

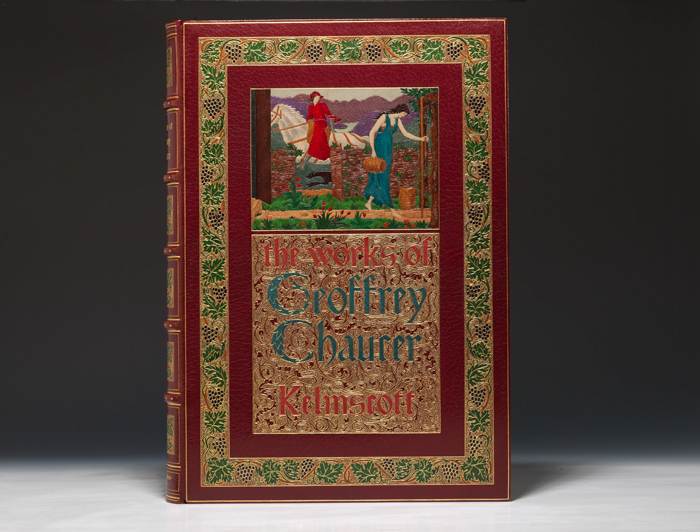

The Canterbury Tales was borne of Chaucer’s reading of Boccaccio’s The Decameron, which is comprised of 100 stories told over 10 days by 10 people escaping from the Black Death. In The Canterbury Tales, we have a group of pilgrims agreeing to a storytelling contest to make less arduous the journey they are to make from London to the shrine of Thomas Becket in Canterbury, Kent. In both works, the authors tell tales of morality, or the lack of, to convey their understanding of the society they lived in. The greatest similarities can be seen in The Story of Patient Griselda from The Decameron and The Clerk’s Tale from The Canterbury Tales.

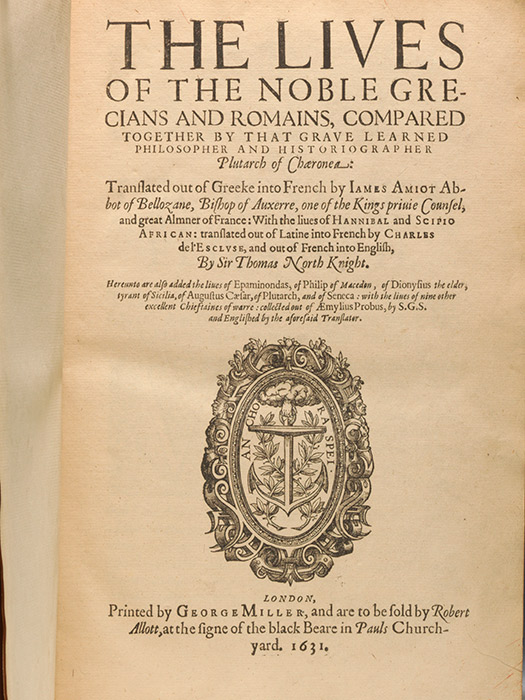

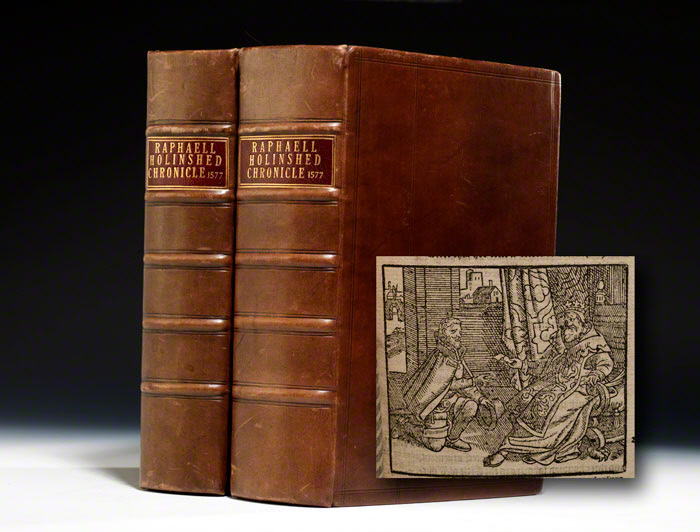

From here The Canterbury Tales and the historical work The Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland by the English historian Raphael Holinshed along with the English translation of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives by the English justice of the peace Sir Thomas North take us neatly to William Shakespeare. With him it would seem all roads meet and lead, for countless writers, artists and filmmakers since owe him a great deal of gratitude. (And let’s not forget the Bible and the influence it had on the Bard. Imagery from the text can be found in numerous plays.)

Plutarch’s Parallel Lives contains biographies of the Greek and Roman soldiers and statesmen that left an impression on their era. It was translated by North and proved extremely popular throughout Renaissance England. Shakespeare took the realism he absorbed from this work to create the dramatic characters found in Antony and Cleopatra, Julius Caesar, Coriolanus and Timon of Athens.

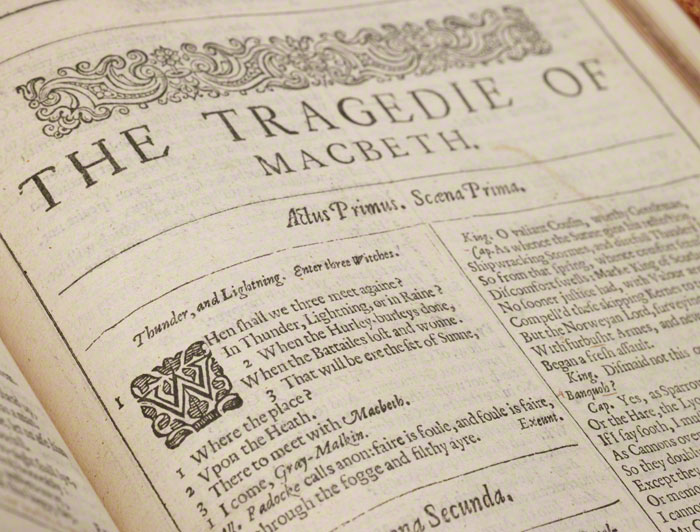

A secondary dose of realism for Shakespeare was Holinshed’s Chronicles. He based his infamous character Macbeth on the less excitable version described by the writer, who in turn based his account of Scotland’s history on the Scotorum Historiae, written in 1527 by the Scottish philosopher Hector Boece.

The number of people who have been influenced by Shakespeare is great. One of his greatest proponents, the poet John Keats, was so taken with Shakespeare’s creativity that he kept a bust of the playwright beside him for inspiration. In a letter he wrote to the English painter Benjamin Robert Haydon in May 1817, Keats wrote:

I remember your saying that you had notions of a good Genius presiding over you. I have of late had the same thought – for things which I do half at Random are afterwards confirmed by my judgment in a dozen features of Propriety. Is it too daring to fancy Shakespeare this Presider?

We shouldn’t be at all surprised by similarities and comparisons between these works. To become great these writers studied the greats before them and in doing so learned their craft. Whether active or through osmosis, the circumstances surrounding these influences are not nearly as important as the results they produced. Fortunately for all of us, these works have survived, and will continue to inspire long into the future.

Sources and Further Reading: