As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, it’s sometimes difficult not to romanticize explorers. Never mind the specifics of terrain or method of transport; never mind the fact that many of us wouldn’t follow in their footsteps for love or money. These guys are out there, doing it. They are, in a very real sense and usually against great odds, filling in the map. And by doing so, they tap straight into a deep cultural vein of mythic, Odysseus-level heroism.

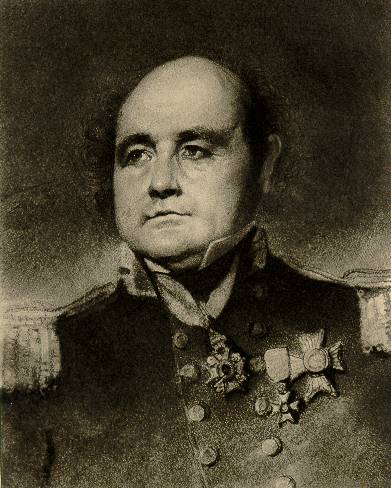

In the annals of Arctic exploration, there is no beast so harrowing as the Northwest Passage. And in the storied history of the Northwest Passage, there is no name so well-known and so associated with tragedy as Sir John Franklin.

Franklin’s first excursion into the Arctic would come to be known as the Coppermine Expedition (1819-1822). The expedition was planned on the quick and cheap. The primary goal was to explore the northern coast of Canada by way of the Coppermine River.

Yet, even with so lofty a goal, the Naval personnel provided was minimal, and the allotted supplies were unlikely to withstand the slightest contingency. Instead, additional manpower and supplies – most notably, food – were expected to be heavily supplemented by local fur traders and aboriginal tribes along the way.

Bonus fact: Two British Arctic expeditions were launched in 1819, both in pursuit of the Northwest Passage. The overland expedition under Franklin’s command and a seaborne expedition led by William Parry. The Admiralty expressed the hope that the two parties would meet along the shores of the polar sea.

As soon as Franklin and his crew landed in Hudson Bay (summer 1819) that plan fell apart. Conflict between rival fur trading companies meant that supplies were limited and unreliable. Voyageurs – who would accompany the expedition as guides, interpreters, hunters – were not readily available. The boats they were provided to navigate Canadian waterways weren’t large enough to haul their supplies.

Chief Akaitcho of the Yellowknives tribe with his son. Akaitcho was

recruited (along with several of his men) to act as guide and hunter

for Franklin’s expedition. The portrait was executed by expedition

member Robert Hood.

When winter came, they had no tents and were instead grateful for snowfall because it provided an extra layer of insulation.

The first leg of their journey was to reach Great Slave Lake, 1700 miles away. It took them a full year.

Bonus fact: The Great Slave Lake is the second largest lake in Canada’s Northwest Territories. It shares its name with the Slavey people, one of Canada’s First Nations.

Bonus fact: During the winter of 1820-21, two of Franklin’s men, George Back and Robert Hood, fell in love with the same aboriginal girl (whom they called Greenstockings) and would have settled the matter via a duel had one of the other Britons not stopped them. (Hood would eventually win the girl.)

When they resumed their journey (summer 1821), they continued north toward the mouth of the Coppermine River. They were eager for their first glimpse of the Arctic Ocean, but as it had everywhere else in Canada, bad luck plagued the party.

The lack of food was never not a problem. There was little game, and the voyageurs proved to be ineffectual hunters. The only aboriginal group they encountered fled from them, so trading wasn’t an option. Storms damaged their boats, which were actually more canoe than boat.

Nevertheless, they managed to map 500 miles of coastline before turning south again. Their goal was Ft. Enterprise, a trading post on the western shore of Great Slave Lake.

For various reasons, Franklin decided they would traverse a region aboriginal tribes referred to as Barren Lands – basically, the tundra.

Barren Lands, little food, an increasingly belligerent crew, and winter was coming – what could go wrong?

Unfortunately for Franklin, the answer was everything.

Stay tuned for Part II, when bad goes to worse and worse goes to catastrophic.