Those who knew him described Adam Smith as dull, a day-dreamer, a hermit, and a hypochondriac, but the philosophical economist was certainly no less brilliant and worldly than his better-traveled Enlightenment contemporaries.

Smith believed human nature combined with the circumstances of society were the driving forces of people’s behaviors and actions, and his study of natural laws made his work revolutionary and influential. Smith was invested in the psychology of commercial society as well as the rights of humankind in the realm of labor and production.

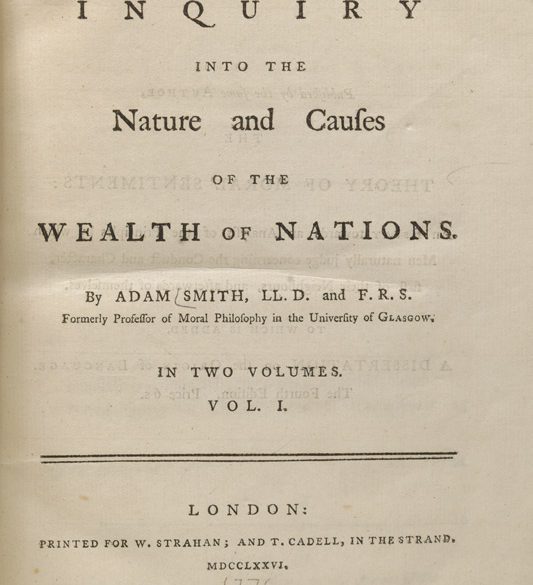

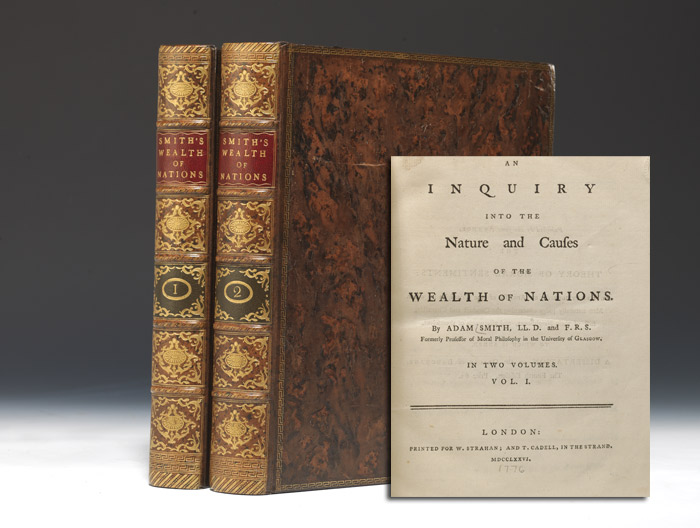

Believing in the “obvious and simple system of natural liberty” (Buchan 111), the theories on political economy that he outlined in his most important work, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, focused on the idea that when an individual follows self-interest, he or she indirectly promotes the good of the population.

Published in 1776, Wealth of Nations influenced the newly independent United States, whose founding fathers gleaned from his work the importance of considering human rights when creating societal systems—hence the Declaration’s reference to “the laws of nature.”

The great ambition in Smith’s ideals is somewhat brought back to earth by Smith’s personal eccentricities, such as his severe hypochondria: He diagnosed himself as experiencing such maladies as “a violent fit of laziness,” “inveterate scurvy,” and “shaking in the head.” Biographers have speculated that Smith’s neuroses possibly derive from growing up without a father, being a sickly child, living only alone or with his mother the entirety of his life in Scotland—not to mention that, according to biographer John Rae, he was kidnapped by gypsies at the age of three. Thankfully, a search party scared the tinkers into dropping him and heading for the hills, to which Rae notes with relief that Smith “would have made, I fear, a poor gipsy” (Buchan 16). So indeed, the troubles that can come along with “the laws of nature” were not lost on Smith.

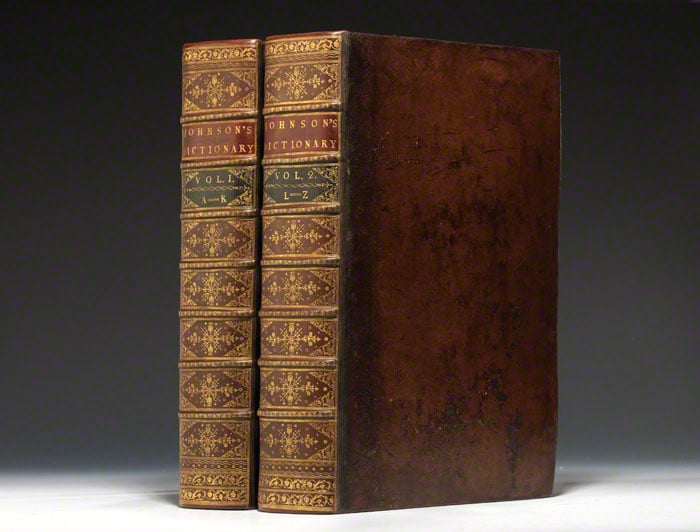

The philosopher and fellow Scotsman David Hume was a friend and a great influence on Smith; Smith himself influenced Thomas Paine and Karl Marx, among other great revolutionaries and thinkers. However, not all of his preeminent contemporaries held him in high regards. The distinguished Dr. Samuel Johnson thought him a day-dreamer who would drift away into thought then come back to reality only to lecture those around him. Johnson relayed his perception to his biographer James Boswell that Smith was “as dull as a dog.”

Johnson’s resentment could possibly be due in part to Smith’s criticism of Johnson’s renowned Dictionary of the English Language, 1755, which Smith thought to be more or less superficial in its failing to show how the human mind has progressed in forming reason.

Enlightenment grudges aside, Smith has come to be known as a great moral philosopher who is considered by many to be the father of modern economics. We here at Bauman Rare Books recognize Wealth of Nations as nothing short of the cornerstone of modern economic thought.

Over the years, Smith’s sage perspectives in Wealth of Nations have been cited by various political and economic camps who want to claim him as their founder or justify various capitalistic intentions. As accurate or skewed as his ideas have been portrayed in modern society, it remains certain that Smith’s influence has been profound.

Whether regarded as the father of the free-market system or a day-dreaming philosopher, Smith imparted on his and future generations the importance of human rights and natural laws in all elements of society, including the cold world of labor and production. And for his great influence, let us be thankful for the relenting of the gypsies.

For more on Adam Smith, please read the authoritative biography by James Buchan: The Authentic Adam Smith: His Life and Ideas, 2006.