In 1886, an elderly and reclusive spinster died in a small New England town, leaving instructions to her younger sister to burn all her surviving correspondences. The town was Amherst, and the spinster was Emily Dickinson, a member of the town’s most prominent families. Lavinia, Emily’s sister, was astonished to find not just the expected letters but also a treasure trove of poems. 1775 in all. Some sewn together in little booklets. Others were loose in drawers.

While it was known that Dickinson wrote poetry, the existence of this exceptional oeuvre was suspected by no one. How this most private collection of poetry escaped the fire and entered the canon of American literature, making Emily Dickinson revered as one of America’s most profound and original poets, is a fascinating story in its own right.

Emily Dickinson’s family and friends knew of her writing. During her lifetime, a few of her poems were published in periodicals such as The Springfield Republican and Drum Beat. But by few, we’re talking about less than a dozen. Imagine her sister’s surprise at stumbling upon those 1775 poems. Though Lavinia did receive instructions to burn Emily’s letters and correspondence, no instructions were left for this unexpected find, which would go on as one of the most influential and discussed voices of poetry.

She was a private person by nature who even as an adolescent preferred isolation, but her seclusion from society grew. It culminated in her speaking to guests through a door rather than receiving them face-to-face. Her intellectual and emotional life has been much discussed and analyzed. Some early scholars have asserted that this stemmed from a failed love affair. Others have regarded this to be a conscious choice to maintain a kind of intellectual and artistic independence and integrity in an age when women were subject to quite severe cultural expectations and constraints. A similar decision was made by some female contemporaries including Jane Austen and Christina Rossetti. Though her reasons remain mysterious, it seems clear that the deeper she receded from society, the more productive she became.

Her retreat from general (“polite”) society did not mean that she did not remain intellectually active. In response to the prominent literary critic Thomas Higginson’s 1862 article in the Atlantic Monthly, “A Letter to a Young Contributor,” Dickinson cheekily replied:

MR. HIGGINSON,–Are you too deeply occupied to say if my verse is alive?

The mind is so near itself it cannot see distinctly, and I have none to ask.

Should you think it breathed, and had you the leisure to tell me, I should feel quick gratitude.

If I make the mistake, that you dared to tell me would give me sincerer honor toward you.

I inclose my name, asking you, if you please, sir, to tell me what is true?

That you will not betray me it is needless to ask, since honor is its own pawn.

Higginson found the young writer to be of talent, but not quite ready for publication. Their friendship continued on until her death. Higginson would later be called upon to make her works public.

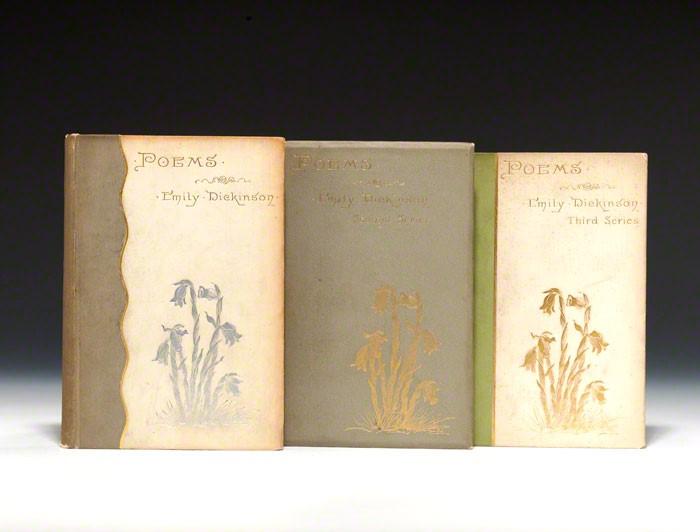

Dickinson’s reputation at her death was that of the “Ghost of Amherst,” an eccentric woman cloaked in white, hidden in her room. But Lavinia’s persistence and recognition of her sister’s genius is what made sharing Dickinson’s work with the world possible. In order to secure publication, Lavinia looked to Mabel Loomis Todd (the wife of an Amherst College faculty member and the mistress of her and Emily’s older brother, Austin). Todd then successfully recruited the help of Thomas Higginson. The Poems of Emily Dickinson, edited by Todd and Higginson, was published in 1890, just four years after her death. This first collection was a small production of only 500 copies. The Second Series followed in 1891, in an addition of only 960 copies. Lastly in 1896, the Third Series was published in an edition of 1000 copies.

While this was a laudable effort, in the process the fascicles (or booklets), assembled by Emily herself, were ripped apart. Furthermore, several of her works were divided between the Todd and Dickinson houses. Differences between the two families, who were both executors of the poems, stopped them from being published all together.

It was not until 1955 that Thomas Johnson brought the complete works together in print, following the text of the fascicles as closely as possible. This means we’ve only a little over half a century to study her entire body of work in a relatively untouched edition, “uncorrected” by the attempts of others to “fix” her signature style of unconventional capitalization and punctuation.

From the moment the poems of Emily Dickinson were revealed to the public, they were patronized and dismissed as curiosities, but as more time passed and more attention accrued, readers have recognized that under the surface of these simple verses are uncompromising questions concerning the most profound issues of human existence, which challenge the intellectual assumptions and social conventions of her time.

Dr. Grant Voth sums it up quite nicely:

From her hermitage in Amherst, Dickinson participated in some of the great literary movements in the world outside… She defied conventions in many ways and as one critic says, “She’s a Romantic in an upstairs bedroom,” a rebel in every way that matters to us.

Further Reading

- Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s 1891 article concerning his earliest correspondences with Dickinson, including numerous excerpts

- Professor Grant L. Voth’s Great Courses lecture on Dickinson in his course History of World Literature provides an excellent short summary of her life and works. For a more in-depth treatment, we recommend the authoritative biography by Richard Sewall, The Life of Emily Dickinson.

- To access more manuscript poems and correspondences, visit http://www.edickinson.org.

Comments

One Response to “Saved From the Flames: The First Series of the Poems of Emily Dickinson”

Ed Leimbacher says: April 1, 2014 at 7:49 pm

No April fool she; instead, Infinity in a Mind, the Universe in a Room. (This is pastiche rather than intended quotation, but I have no doubt she used these very words in glorious constructs rather than, as here, mere pedestrian praise.)