You can see what I do if you choose. Work up imagination to the state of vision, and the thing is done.

–William Blake

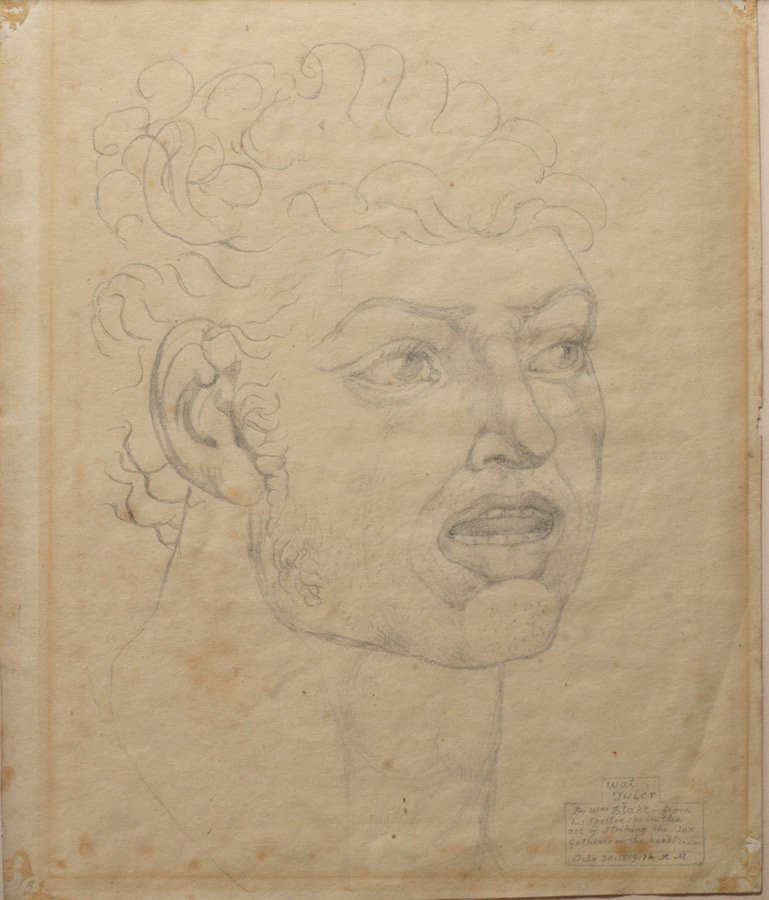

Over the years we’ve had books written or illustrated by William Blake (1757-1827), the influential artist, engraver, poet, and radical thinker of the Romantic Age. Blake has often been called a visionary, which may have been literally true—throughout his life he claimed to see visions that inspired his art. One of the most dramatic examples of this is his famous series of “Visionary Heads” drawings, which Alexander Gilchrist described in his seminal 1863 Life of William Blake as “some forty or fifty slight pencil sketches, of small size, of historical, nay, fabulous and even typical personages, summoned from the vast deep of time, and ‘seen in vision by Mr. Blake.’”

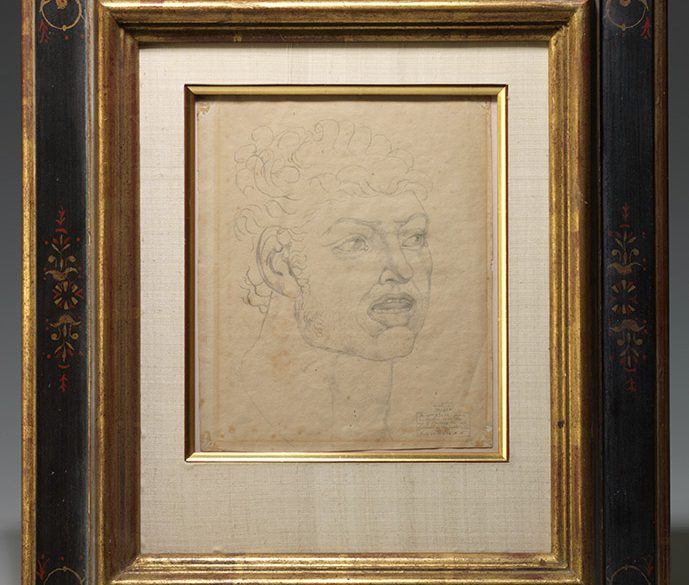

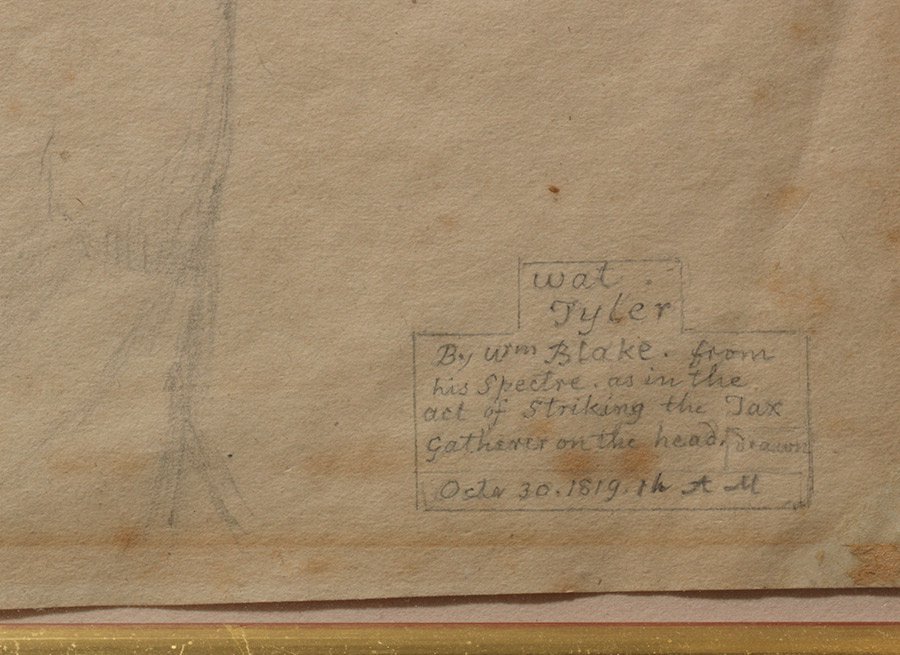

We now have a truly remarkable Blake rarity—one of Blake’s original “Visionary Heads” drawings, depicting Wat Tyler, the leader of the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt. The drawing is inscribed by Blake’s friend John Varley, identifying the subject and the date and time of composition: “Wat Tyler By Wm Blake, from his Spectre, as in the act of striking the Tax Gatherer on the head, drawn Octr 30, 1819, 1h AM.” Most of the “Visionary Heads” drawings were created in 1819 and 1820, and this is one of the earliest dated drawings; the earliest is dated October 14, 1819, and only five are dated in that month and year.

Blake drew his “Visionary Heads” for John Varley, the landscape painter and astrologer who became his close friend in 1819. Here’s Gilchrist’s fascinating description of their creation:

At Varley’s house, and under his own eye, were drawn those Visionary Heads, or Spiritual Portraits of remarkable characters… Varley it was who encouraged Blake to take authentic sketches of certain among his most frequent spiritual visitants. The Visionary faculty was so much under control that, at the wish of a friend, he could summon before his abstracted gaze any of the familiar forms and faces he was asked for… Varley would say ‘Draw me Moses,’ or David; or would call for a likeness of Julius Caesar, or Cassibellanus, or Edward the Third, or some other great historical personage. Blake would answer, ‘There he is!’ and paper and pencil at hand, he would begin drawing, with the utmost alacrity and composure, looking up from time to time as though he had a real sitter before him; ingenuous Varley, meanwhile, straining wistful eyes into vacancy and seeing nothing, though he tried hard, and at first expected his faith and patience to be rewarded by a genuine apparition.

If you’re asking yourself whether Blake was crazy, you’re not alone—many asked that during his lifetime and the question is still debated today. Gilchrist even titled a chapter of his biography “Mad or Not Mad?” in which he noted that in conversation,

Blake would speak in the most matter-of-fact way of recent spiritual visitors. Much of their talk was of the spirits he had been discoursing with, and, to a third person, would have sounded oddly enough. ‘Milton the other day was saying to me,’ so and so… Listeners hardly knew sometimes whether to believe Blake saw these spirits or not; but could not go so far as utterly to deny that he did… According to his own explanation, Blake saw spiritual appearances by the exercise of a special faculty—that of imagination… He said the things imagination saw were as much realities as were gross and tangible facts.

After reading Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience, William Wordsworth said,

There was no doubt that this poor man was mad, but there is something in the madness of this man which interests me more than the sanity of Lord Byron and Walter Scott!

Given Blake’s radical political and philosophical views, it’s not surprising that he chose Wat Tyler as one of his subjects, as he was the leader of England’s first great popular rebellion, the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt against Richard II’s poll tax. Tyler became a popular figure for artists and writers during the French Revolution and through the early 19th century, such as Thomas Paine, Edmund Burke, and poet Robert Southey.

The provenance (ownership history) of this drawing traces all the way back to the collection of John Linnell, Blake’s friend and patron during his last years, who introduced Blake to Varley in 1819. This drawing, #737 in Martin Butlin’s The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake, was exhibited at the Fogg Museum in 1930 and at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1939.

We are privileged to offer such an extraordinary piece of art and history. For more information about this Blake drawing, see our description or contact our galleries.

Comments

One Response to “Spotlight: Blake’s “Visionary Heads” Drawing of Wat Tyler”

Mike says: October 21, 2014 at 9:37 pm

Love Blake, although half the time I don’t know what he’s talking about.