Once or twice during my academic years I was accused of reading the dictionary. Although untrue, I’ll admit I have skimmed a page or two upon occasion; I do readily look up the meaning of unfamiliar words, and I did ask, and receive, a copy of the Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (with reading glass) when graduating with my MA.

I guess there is some personal fascination with the dictionary, but who doesn’t appreciate a well-chosen word, a lovely turn of phrase, or the etymology of an interesting term?

In 1928, when the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) was finally completed after a little over seventy years, British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin began his toast with the remark that if he were lost on a deserted island, he would choose the OED for company because, “Our history, our novels, our poems, our plays — they are all in this one book.” I fully agree.

The OED sprang as an idea in 1857 from several members of the Philological Society in London. They felt that the current dictionaries were not comprehensive or accurate enough. An ideal dictionary would contain all obsolete words, all families and groups of words, accurate documenting of the earliest appearance of the words, detailed meanings and senses of words, and all literature had to be read and scanned for illustrations of these meanings. To sum it up, the best dictionary needed to contain the meaning of everything.

That is quite a request. Monumental, indeed.

The illustrative quotes are the essence of the OED; these reveal the history and usage of the language through the centuries. But, how was all literature to be read, all the words listed, and the earliest appearances found? By making a call to the public, asking for volunteers around the English-speaking world “to read and extract” quotations from various books. The dictionary was for the people, so why not have them help research it? And they did. Ultimately, more than 800 readers responded with their assistance.

Besides these readers, the OED required the work of many others: sorters, sub-editors, assistant editors, editors, compositors, printers, proofreaders, professional authorities, delegates, and Oxford deans. The poets Tennyson and Browning were consulted about the meaning of words that appeared in their poems. J.R.R. Tolkien was an assistant lexicographer for one year, 1919. No less than six editors guided the process, with the bulk done by James Murray. Even several of Murray’s children helped through the years.

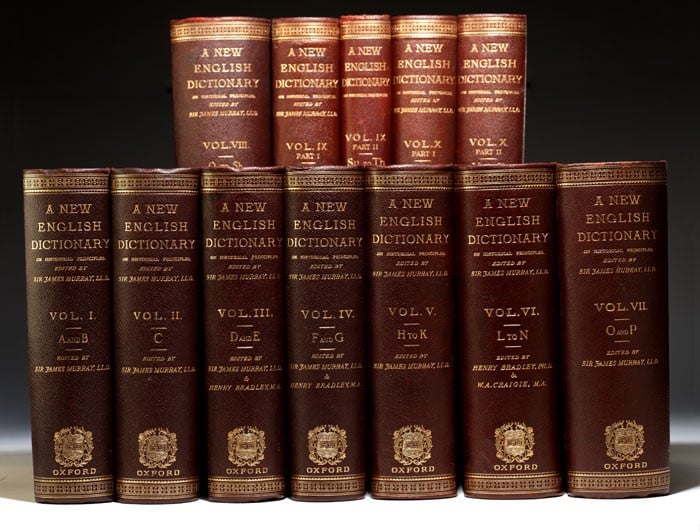

This gargantuan project required a lot of paper, man-hours and time. Here are some dizzying facts about the 10-volume first complete edition of the OED:

- The first fascicle was published January 29, 1884; the last completed on April 19, 1928

- A full set was priced at 50 guineas – about eight-tenths of a penny per page

- The most quoted work was a 14th-century poem Cursor Mundi

- The type would cover 178 miles

- 1,827,306 illustrative quotations were provided

- It included 414,825 words

If you are inclined to read the OED, even at a word a day, the original 400,000+ words would take over 1000 years to read. In the meantime, what’s your word-of-the-day?

Further Reading

- If you’d like to know more about the OED, I highly recommend both of Simon Winchester’s engaging histories: The Meaning of Everything and The Professor and the Madman.

- The official website of the OED also includes a page on the history of the dictionary here.

Comments

3 Responses to “The Story Behind the Creation of the Oxford English Dictionary”

Richard Chelvan says: March 15, 2019 at 12:00 pm

I don’t know what I would do without my Oxford dictionaries and lexicons! Latin and Greek! Especially my Patristic Greek Lexicon or even my Lewis & Short Latin Dictionary!

Scott Byerly says: December 17, 2020 at 8:36 pm

Mary,

How would one go about getting an original example of the appeal that went out to the general public., ie. ‘Unregistered Words Committee’ of the Philological Society of London 1857 pamphlet. I’d like to purchase one. Thank you.

Mary Olsson says: December 23, 2020 at 3:33 pm

Hi Scott,

Finding such an example would be very exciting, though also challenging. I think your best source would be booksellers/dealers who focus on ephemera. You might do a search for such an appeal with various dealers on ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Booksellers) with a focus on those in the UK. Good Luck!

Mary