Engraving has suffered from an identity crisis, perhaps born from its ubiquity. Humans have used engraving as a tool for expression in every era and every place, from prehistoric cave drawings to modern mall kiosks. This saturation has transformed engraving into a blanket term for nearly all types of early illustration including woodcuts, lithographs, and the misleadingly named wood engravings.

So, what is an engraved illustration? Engraving falls into the intaglio print process category, meaning ink is forced into carved out lines and then deposited onto paper using a great amount of pressure, unlike relief woodcuts and wood engraving where ink meets paper through a surface stamping method. Engravers dig into copper and steel plates as opposed to wood. This simplified the illustration process, as artists no longer needed to focus on negative space.

Though technically simple, it took until the 15th century for printers to embrace engraving. Early adopters of metal engraving often began their careers as goldsmiths. Not surprisingly, early engraved illustrations remained luxury items available to very few people. Collectors still prize prints from this era due to their exceptional scarcity.

A notable example of an early engraving artist is a mysterious character referred to as “The Master of Playing Cards.” We know little about this artist other than the small amount of work that remains—just over one hundred examples of prints derived from engraved copper plates. Many of these prints were used to form an elegant deck of illustrated playing cards.

Metal engraving, particularly using copper plates, became an ideal medium for reproducing artwork and mapmaking, but it never succeeded in the print market to the same extent as etching and relief processes. Part of the reason was practicality. Although copper makes for an ideal engraving surface due to its malleability, each pass through the press slowly erodes the artist’s line work. The first printed pages appear crisp and bold, whereas continued pressings produce uneven lines and decrease tonal differences. Steel plates last longer, but are impractical for all but the strongest of hands.

Electroplated copper, called steel-faced plates, appeared in the mid 1800’s and combined the best of both metals. Steel-faced plates would still wear away, but the copper could then be replated for continued use, ensuring a greater number and higher quality of printings. Still, engraving never gained great favor among printers of the era.

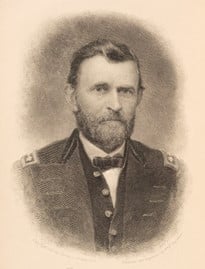

Engraving has an unmistakable appearance on close-inspection. The lines are tapered and pointed at the end, swelling gracefully in the middle—perfect for producing swooping curves. Portraits work best as engravings, allowing for great detail and a surprising amount of depth and tones.

A few standard patterns should be instantly recognizable as engravings such as dot-and-lozenge–a type of crosshatching using a diamond pattern with a dot in the center–and parallel lines grouped in different thicknesses, a technique that creates depth.

Let’s take a closer look at the techniques used in the steel-engraved frontispiece portrait of Ulysses S. Grant taken from the 1885-86 first edition of his Memoirs.

Upon closer inspection of General Grant’s cheek, the dot and lozenge technique reveals itself.

An example of parallel lines grouped together in varying thicknesses to create depth is seen in this close-up of General Grant’s hair.

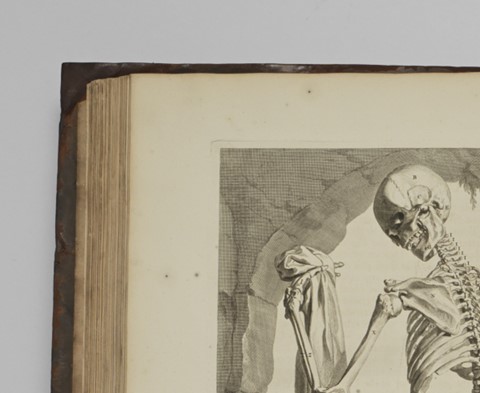

Plate marks and illustration size also help identify engravings. Plate marks result from the pressure of the printing process. The force exerted leaves a faint impression of the plate frame on the page. Illustration size provides further clues. Combining steel engravings with typeface created logistical problems, so these illustrations usually occupy a full page. Printers generally relied on wood engravings or woodcuts to integrate both text and illustration onto the same page.

From the 1737 second edition of William Cowper’s Anatomy of Humane Bodies.

Great engravers are not difficult to come by, but one particular artist of note is William Hogarth. Born in 1697 in London, Hogarth tackled a variety of artistic mediums and careers (and, in the great tradition of engravers, even apprenticed as a goldsmith) before becoming known for his satirical comic-like vignettes and a series of moral works that began with A Harlot’s Progress in 1731.

Hogarth’s work contained satirical elements and reflected contemporary middle class concerns. He tackled subjects such as debtor’s prison, alcoholism, and prostitution. Although he focused on gritty subject matter, his work contained grace. He popularized the concept of the “line of beauty,” a smooth, flowing “S”-shaped curve used to provoke a feeling of excitement and life. Hogarth’s prints and books are still highly sought after by collectors today.

For another great example of a work with steel engravings that is currently available, take a look at the following:

#116306 Gallery of English and American Women Famous in Song