At the end of the 18th century, Thomas Bewick flipped over a dense piece of boxwood and, with that simple gesture, he transformed the art of relief printmaking. Bewick discovered that, by carving against the grain of the wood rather than with it on the plank side (as with a woodcut), finely detailed relief carvings could be achieved with much greater ease.

The trend took off and soon wood engravings dominated print. They were valued by the public for their beauty and by artists for their ease, but mostly by printers for their cost-effectiveness. Wood engravings, like their predecessors, woodcuts, could be slotted next to typeface in a printing press. With a single pass through the press, illustrations and text could be printed together, resulting in much higher production speeds.

Despite the misleading name, wood engravings remain part of the relief family of illustrative processes, in which ink is deposited onto the raised portions of the carving. Only light pressure is needed to transfer the ink to paper, prolonging the sharpness of detail in the original carving. This stands in sharp contrast to the quick deterioration of softer metal engravings. Wood engravings proved to be resilient and versatile.

Great detail and tonal qualities can be achieved with wood engraving, so identifying prints requires a keen eye and a magnifying glass. Engravers often create images relying on ‘white lines’ to define the image, whereas woodcut artists focus on the black outlines. Close inspection of a wood engraving reveals the deliberateness of the white portions as compared to the inked lines.

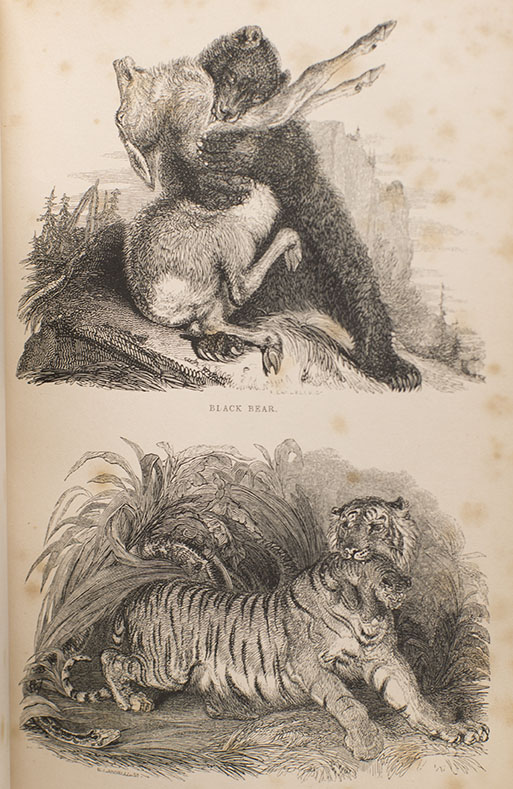

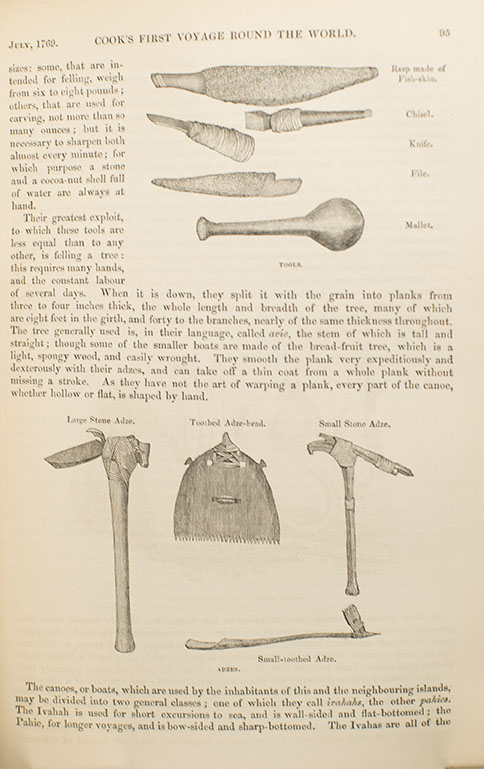

Wood engraving was not just for large illustrations. Smaller in-text illustrations were nearly always wood engravings (or occasionally woodcuts), as intaglio techniques required a separate step in the printing process. Full-page steel or copper engravings were frequently combined with smaller wood engravings in late 19th century works.

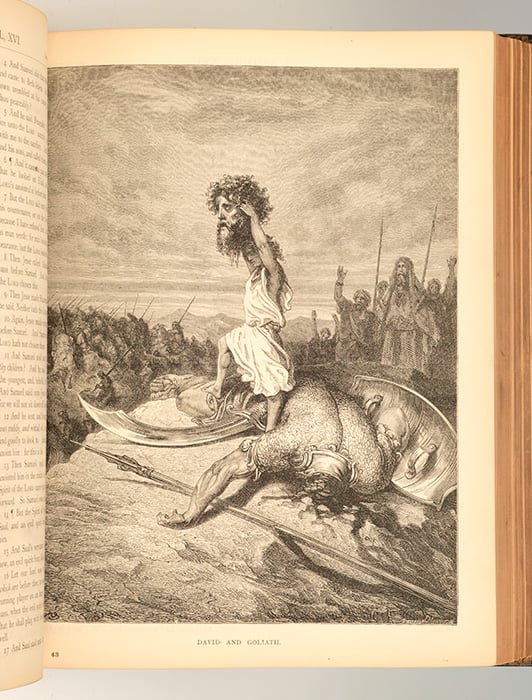

Although steel engravings proved popular for full-page illustrations, occasionally artists would return to relief methods. Gustave Dore, a French illustrator, took advantage of the technique for his ambitious rendition of biblical scenes in the 1866 illustrated edition of Le Grande Bible de Tours. The original work, a two-volume folio set, consisted of 241 wood engravings based on the Vulgate Bible. Dore’s Bible proved to be a wild success–so much so that several subsequent editions would follow.

Few works are better suited for dramatic and dynamic illustrations than the Holy Bible, and there is no finer example of wood engraved illustrations than Dore’s biblical scenes. Dore illustrated several other notable works including Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven, Miguel de Cervantes Don Quixote, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

Wood engravings often proved to be collaborative efforts between the original illustrator and several engravers who specialized in different areas such as backgrounds, shading, or figures. A single engraving could be completed by a lone artist or with the assistance of an entire workshop.

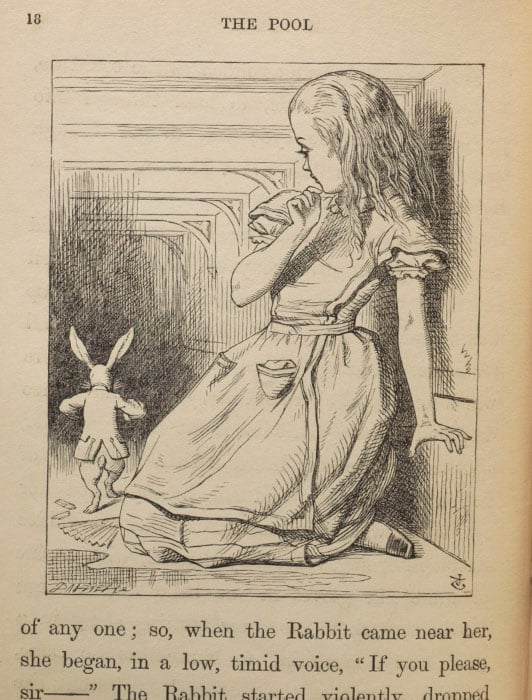

An important example of one such collaboration is the Lewis Carroll classic, Alice in Wonderland. John Tenniel created his iconic illustrations for the children’s tale directly onto boxwood blocks. Master Victorian engravers, the Dalziel brothers, then carved out the pictures in relief. Tenniel worked closely with the brothers, overseeing every scoop of their graver, resulting in intricately detailed reproductions of his original sketches. That high level of accuracy proved problematic. The delicate nature of the engravings could not have withstood the unrelenting pressure of the printing press, so the decision was made to use the Dalziel wood engravings as the basis for sturdier electrotype copies. Some of the sharpness of the engravings was lost, but there was no risk of destroying the valuable master blocks.

This late addition to the cadre of relief printing methods made it possible to introduce some of the greatest illustrated works of all time to a wide swathe of readers. It also helped to jumpstart the Golden Age of children’s literature.

For more great examples of wood engravings, check out the following titles:

Uncle Remus: His Songs and Sayings, Joel Chandler Harris

Tower of London, William Harrison Ainsworth