Ladies and gentlemen, you are about to hear the truth of an old legend that has persisted wrongly through the ages;

the truth, until now hid behind the embroidered curtain of a rhyme, about the Knave of Hearts, who was no knave but a very hero indeed. The truth, you will agree with me, gentlemen and most honored ladies, is rare! It is only the quiet, unimpassioned things of nature that seem what they are. The high majesty of clouds, rolled in massy radiance against the blue; pines shadowed deep and darkly green, mirrored in still waters; the contemplative mystery of the hills – these things which exist, absorbed but in their own existence – these are the perfect chalices of truth.

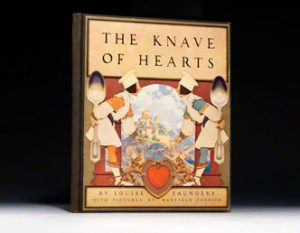

Unlike the other titles highlighted in this series, Louise Saunders’ Knave of Hearts is actually a play – complete with a dramatis personae and stage directions. And given that the play begins when The Manager appears before the curtain, gives a courtly bow, and launches into the above speech regarding truth, I ought begin with a small confession: Past that first paragraph, I haven’t actually read Knave of Hearts.

After an impromptu poll of my colleagues, I can tell you I’m not the only one. But, with sincerest apologies to Louise Saunders, the play is not the main attraction here – it’s the illustrations by Maxfield Parrish.

Raised in Philadelphia, Parrish was encouraged in his artistic leanings from a young age by surprisingly supportive parents. (Parrish’s father, who was himself an engraver and painter, had been stifled as a youngster by a strict Quaker upbringing.) Parrish studied and traveled extensively – both in the United States and Europe. He was briefly the student of the great Howard Pyle. (Pyle, by the way, was as quintessential an American artist as Norman Rockwell ever was.) By the time he was 30, Parrish had established himself as an incredibly successful commercial artist and illustrator of children’s books and magazines.

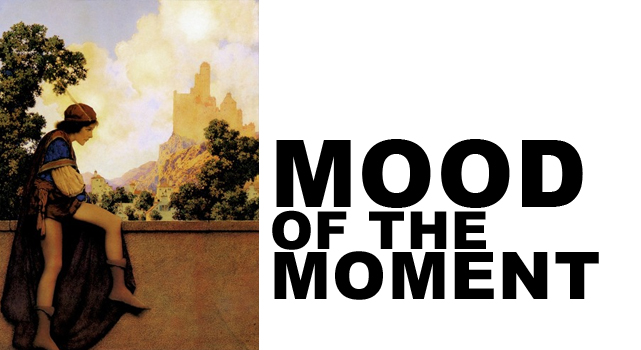

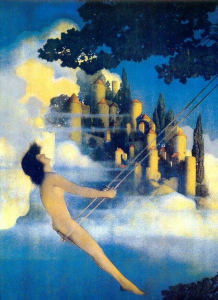

Published in 1925, Knave of Hearts features 14 color plates and 9 in-text color vignettes. A huge part of what sets Parrish’s art apart is the depth and saturation of color he employs – especially his blues. (Cobalt blue is sometimes referred to as Parrish blue.) His art also blends intense photographic detail with the soft romanticism of Pre-Raphaelite artists like Rossetti and Burne-Jones – what one critic refers to as -suggestiveness without loss of unflinching detail.

The artist himself describes it as “realism of impression, realism of mood of the moment, yes, but not realism of things.”

Parrish illustrated numerous other children’s books, including Arabian Nights, Mother Goose in Prose (with L. Frank Baum), and Dream Days (with Kenneth Grahame). As evidence of the small ironies that sometimes crop up in book collecting, Knave of Hearts stands as the most sought-after of Parrish’s children’s books, but his most famous illustration – “The Dinky Bird” – appears in Poems of Childhood by Eugene Fields.

Knave was the last of Parrish’s children’s books. It also appears to be the last of Louise Saunders publications. (Another book of plays, Magic Lanterns, was published in 1923.) It’s worth noting that she was married to Max Perkins, perhaps the most famous literary editor of the 20th century. He both ‘discovered’ and nurtured F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and Thomas Wolfe.

One of the aspects I enjoy most about my job is finding the small, tangential, or otherwise unexpected threads that connect writers and artists to other writers and artists. Louise Saunders being married to Max Perkins is only one example. Another is the fact that one of Parrish’s mid-career commissions was for a book called Italian Villas and Their Gardens, which was published in 1904. This same book also happens to have been one of Edith Wharton’s earliest official publications. What are some of your favorite literary connections?

Comments

3 Responses to “The Knave of Hearts Illustrated by Maxfield Parrish”

Sandy Royle says: June 24, 2015 at 9:48 am

Enjoyed your insight. We have this book, in very good condition. No tears, has very good color. Still all pages intact. Can you give me an estimate of its worth? Thank you.

Scott Robertson says: July 21, 2015 at 1:57 am

Sorry, I don’t know where I got the idea that Parrish and Saunders were neighbors. Parrish lived in Plainfield, New Hampshire, and Saunders lived in Plainfield, New Jersey.

Jennifer McDermott says: January 16, 2018 at 1:22 pm

Have you ever seen studies done for these illustrations?