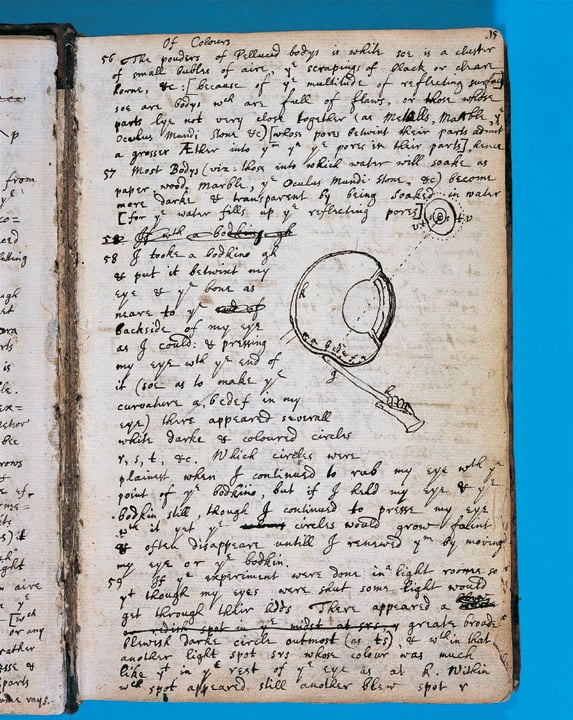

Long before his magnum opus on theoretical physics was published, a young Sir Isaac Newton was sticking needles in his eyes. Equipped with a voracious intellect from a young age, this “experiment,” as he called it, was to determine whether color was a product of events outside the eye or within.

When the experiment failed to yield definitive results – beyond black and white spots appearing wherever pressure was applied by the needle or bodkin – Newton turned to less invasive methods to further his investigation. Developing over a few years a series of increasingly elaborate and refined experiments using prisms, he eventually enjoyed the breakthrough he was seeking when sunshine entering a darkened room and, passing through a prism, diffracted. He described beautifully the rainbow effect he witnessed as “the colour’d Image of the Sun.”

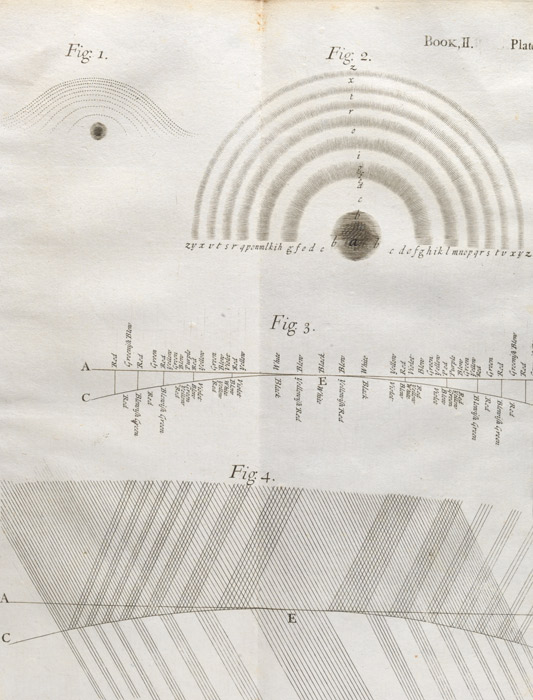

Prior to this revelation, it was widely believed light was pure and that colors originated from elsewhere in the physical world when matter came into contact with light, most typically from the sun. Newton’s experiment, however, showed that light is in fact a compound of many primary colors, which can be separated out and mixed together to form additional colors at will – diffraction, which Newton called the “inflexion of light.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this theory was met with persistent skepticism from the scientific community, including the Dutch mathematician Christiaan Huygens and French physicist Edmé Mariotte, with the latter failing to duplicate Newton’s experiments.

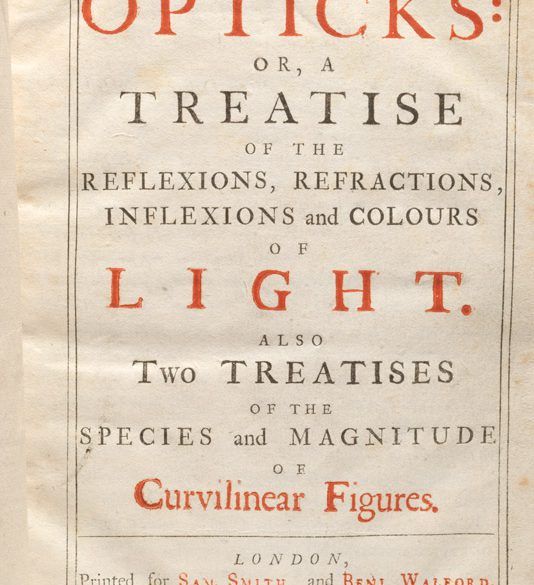

As such, the publication of Opticks or a Treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and Colours of Light was delayed by Newton until the critics were, for the most part, dead. When it was released in 1704, more than 30 years after he first began sticking needles into his eyes, the work detailed his prism experiments as well as other experiments and deductions.

Written in English and in prose, the book was accessible to a far greater audience than his first work, Principia Mathematica, which was composed in Latin and required intricate mathematics to explain the theories within. As a result Opticks became the authoritative work on the study of light through the eighteenth century, as well as having a greater influence over natural science in general.

In Opticks you will find 33 years worth of Newton’s discoveries and theories concerning light and color, from the spectrum of sunlight to the invention of the reflecting telescope. Also included is the first workable theory of the rainbow, as well as the first color circle in the history of color theory. All of this, as well as remarks on other subjects including metabolism, the circulation of blood and an examination of the haunting experiences of the mentally ill.

And to think this first issue was published anonymously, with only the initials “I.N.” at the end of an advertisement at the front of the book.

Comments

One Response to “The Story Behind Opticks by Sir Isaac Newton”

James says: December 21, 2013 at 8:36 am

I remember reading earlier this year of Thomas Young’s experiments, which involved jamming measurement instruments into his eye sockets as far as he could in order to understand the mechanism behind accommodation. You have to admire the dedication of these fellows!