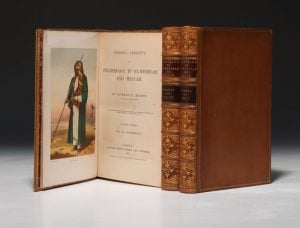

In the spring of 1853, noted linguist and explorer Richard Francis Burton started his most famous and important journey. Burton undertook the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina, a trip that few Europeans knew anything about, and even fewer Europeans had ever undergone before. It would result in one of the greatest travel narratives ever written by an Englishman: Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to El-Medinah and Meccah (1855-56).

There was quite a bit of pride in such a dangerous undertaking for an intrepid explorer like Burton. Of the journey he said he wanted to “prove, by trial that what might be perilous to other travelers was safe to me.”

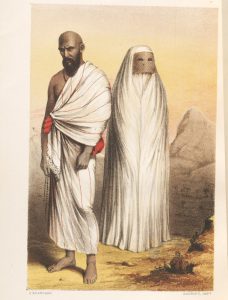

He started as a kind of “Persian prince” but soon settled on a dervish, a Sufi Muslim who lives an ascetic life dedicated to holiness. It was handy disguise, as dervishes could be of any social station, any age, from an (Muslim) country, and go anywhere they wished without questions from other Muslims. Eventually he created an elaborate backstory of an Afghan born in India and educated in Burma (to cover up any possible errors in his linguistic abilities with Arabic, Persian, or Hindustani).

Could Burton have visited Mecca as an Englishman converted to Islam, rather than in disguise? It probably would have been possible, but Burton did not want to take that path:

…my spirit could not bend to own myself…a renegade—to be pointed at and shunned and catechized, an object of suspicion to the many and of contempt for all.

Burton wanted to visit Mecca unremarked, as any other Muslim could.

When Burton first began his journey, it had been some time since he had last lived in a country with Muslim customs. He spent a month or so in Alexandria learning all over again the right ways to eat, drink, sit, sleep, and of course, pray. The tiniest misstep might be a betrayal—literally: the proper way to enter a mosque was with the right foot first. According to Burton’s account, most Muslims who ran into him thought he was certainly Muslim, but “not a good one like themselves, but, still better than nothing.”

One problem Burton faced during his journey was the difficulty in taking notes for his planned book. The people around him viewed taking notes as a “Frankish habit,” so taking notes could bring suspicion down on him. Burton took to carrying a case meant to hold a small Quran and snuck an empty notebook in it instead.

His journey wasn’t without some mistakes. In Cairo, Burton exchanged drinks with an Albanian soldier after a small altercation. However the drinks got a bit out of hand and the soldier caused a major ruckus, drawing attention and shame upon the “Indian doctor.” He had drunk something forbidden to practicing Muslims, and word got around. Burton slunk away from Cairo at his first opportunity. (Burton continued to drink on his pilgrimage, but only secretly.)

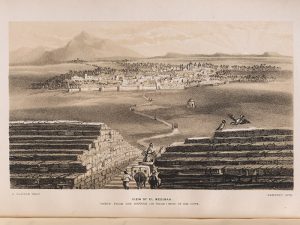

Burton first visited Medina, the location of the Prophet Mohammad’s tomb. In Burton’s day so little of Muslim culture had been correctly communicated to Europeans that many still believed Mohammad’s tomb was actually in Mecca. Burton was now a Zair, a pilgrim who had visited Medina. (The pilgrimage to Mecca would make him a haji.)

Always on the lookout for content scandalous to Victorian sensibilities, one of Burton’s interests in Medina was the practice of female circumcision. Though Burton wrote about it extensively in his Pilgrimage, his editor deleted most of these passages as “unpleasant garbage.”

Although Burton felt his trip to Medina somewhat underwhelming, Mecca and the Ka’aba (one of the most sacred sites of Islam) did not disappoint. “Few Moslems contemplate for the first time the Ka’abah, without fear and awe,” Burton noted. He followed all the proper steps of the pilgrimage—distracted every now and then, in true Burton style, by some exotic young beauty—and finally became qualified to wear the green turban of a haji.

Then it was back towards home. He appeared at the door of the British consul in Jeddah—whose doorman refused to admit him, as he was still dressed as an Arab. Burton had to send in a note that he was “an officer of the Indian army,” which led to a considerable amount of surprise, but a warm welcome.

His return to London brought mixed reactions. Englanders took pride in him as a bold British traveler. However when Muslims received word of Burton’s successful trip, many viewed it as blasphemy. Among Europeans, Burton continued wearing Arab dress and otherwise keeping up controversial (in their minds) Muslim practices.

Bold and controversial: two appropriate adjectives for Burton and his career. His Pilgrimage encompasses both of these perhaps more than any of his other works. Mixed with the keen eye of an anthropological observer and the passion of a man in love with the culture, his book stands as a triumph in the field.

Comments

12 Responses to “The Story Behind Richard F. Burton’s Pilgrimage to Medina and Mecca”

Michael says: August 12, 2013 at 7:49 pm

Great article. I always wanted to know more about the travels of Burton. An interesting tidbit: I first came across him in a mystery novel by John Dunning who I had the pleasure to meet at the Denver Book Fair several years ago. Mr. Dunning’s protagonist, Cliff Janeway, was on search for the “lost” journal of Burton’s when he spent time travelling In the United States. The journal was made up for the story and intertwined but Janeway needed to find it to solve the novel’s mystery. Ever since I have wanted to know more about Burton and thank you for taking the time to enlighten me.

Ken Bellanca says: August 12, 2013 at 9:21 pm

Read this many years ago. It’s good to see that you are reviving interest in it. In fact, you have moved me to try it on my iPad.

Richard says: August 12, 2013 at 11:47 pm

Very interesting, would love to read it, nice engravings, beautiful books.

You would love Worcester’s “Sketches of Earth….” it contains a great account of Mecca, and an astounding etching of the central shrine.

William Joy says: August 13, 2013 at 9:21 am

Excellent post, Rebecca, regarding this famous journey by one of England’s most fascinating explorers. Of course, Burton would have many more adventures following his pilgrimage to Mecca… notably his attempt to find the source of the White Nile, with his friend and later rival, John Hanning Speke (and during which, he would acquire the javelin wound that scarred him for life, as you pointed out).

Mike Carroll says: August 13, 2013 at 12:14 pm

Hi Rebecca,

Thanks for continuing to inform all of us about books we would never have the chance to see or read. Sorry about all the controversy about your appearance. I watch Pawn Stars always , but I especially like the experts because I can always learn something new.

Thanks for the enlightening me on Burton and his travels 🙂

Ross says: September 8, 2013 at 9:24 am

Thank you for this summary. I have attempted Burton’s Arabian Nights but his style is so Victorian Orientalist and the abundant footnotes so distracting. In the early pages he’s already digressed to a note regarding the qualities of the “members” of black races as he has observed and recorded them.

Perhaps the inflammatory wife was more critic than prude.

Thank heavens for the new and complete Lyons translation.

Dr Rais Ahmed Samdani says: November 16, 2013 at 5:36 am

Nice to read this post, Rebecca, this is a famous journey of Burton to Madina and Makkah. Presently I have a read a book which is in Urdu Llanguage entitled “Harmain Ke Musafir” by Rafiuzaman Zubairi. There is a story of Burton’s journey of Madina and Makkah. Interesting and informatiive story. Thanks to Robecca.

shaker says: July 12, 2018 at 12:16 am

I have a question: Did he sucess to bring some pieces from the black stone located in the Kaaba and whether the specialists examined these pieces ,, thanks

Jack says: July 17, 2018 at 9:38 am

Execuse but is it true that he become a muslim after his trip?

And did he steal the black stone ?

Tarek says: July 16, 2021 at 11:53 am

Have you got any answer so far?

Jessa Feiler says: July 21, 2021 at 10:17 am

I can’t speak with regard to Jack, but I can tell you that Burton’s relationship with Islam was complicated. Although he followed Islamic tenets during much of his life, he also repeatedly engaged with Catholicism including by receiving last rites on his deathbed. He also declared himself an athiest and cited the Church of England as “his church.” I think it’s fair to say that he was fascinated by religion–Catholicism, Islam, Anglicanism–and that living a Muslim lifestyle allowed him to break new ground as a traveler and authority on the Middle East. As far as the black stone, it’s probably stolen as much as any other type of Western museum artifact originally from the Middle East is (i.e. removed from its original home). To be clear, it was not and never has been part of the stone inside the Kaaba. He just happened to call both stones meteorites due to a lack of geological knowledge and a flair for the dramatic. Burton is believed to have worn his stone around his neck. We now know it to be a piece of quartz rather than a meteorite and research continues on the Kufic script etched on it (but it has been dated to 600-1100 AD, so possibly contemporary with the Prophet Muhammad or possibly well after).