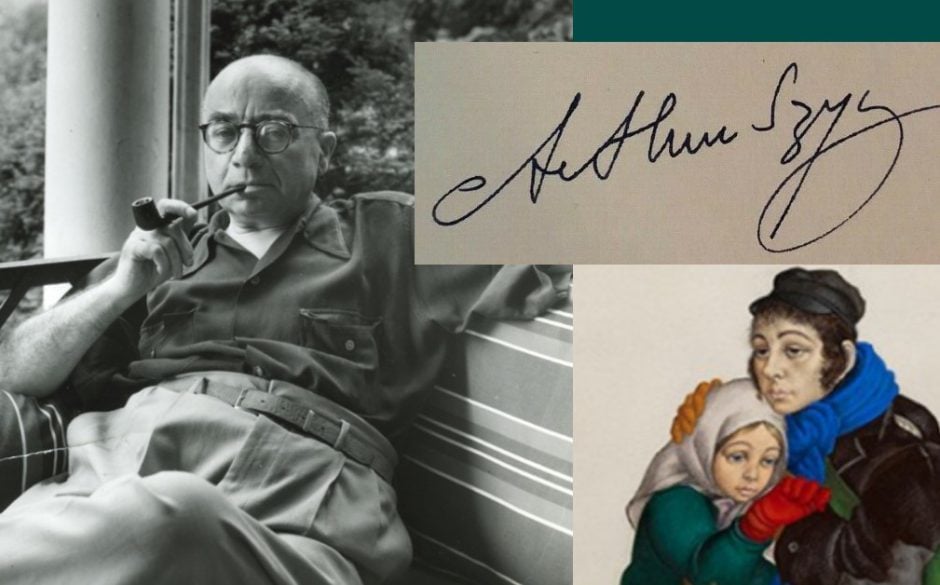

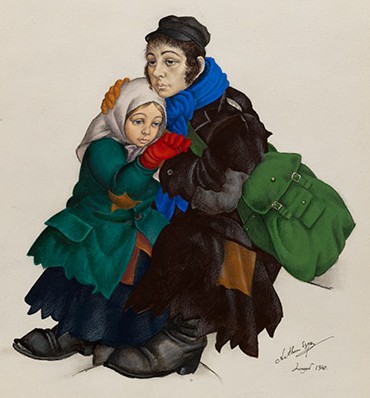

For this installment of The Weird and The Wonderful, I’m heading off-piste and into the world of art and illustration. At Bauman, we call this category “Not a Book”… but I like to think we say that with love. After all, our manuscripts, art, illustrations, and historical objects constitute some of our best inventory. This week, I want to take a look at one of my favorite “Not a Books”: Arthur Szyk’s War Orphans.

I get it: your first reaction is “Wow, that’s bleak.” But it’s also beautiful and powerful. Szyk depicts two children in tattered clothes with thousand-yard stares and tells the story of a continent, the trauma of a generation. Ultimately, it’s a painting about love and survival in desperate times.

In the world of 20th century art, Arthur Szyk sticks out. While his European contemporaries such as Chagall, Magritte, and Picasso were exploring the surreal and the abstract, Szyk was actively rejecting modernism. Instead, he turned to medieval art, the Renaissance, and caricature, using familiar techniques to convey sharp political messages.

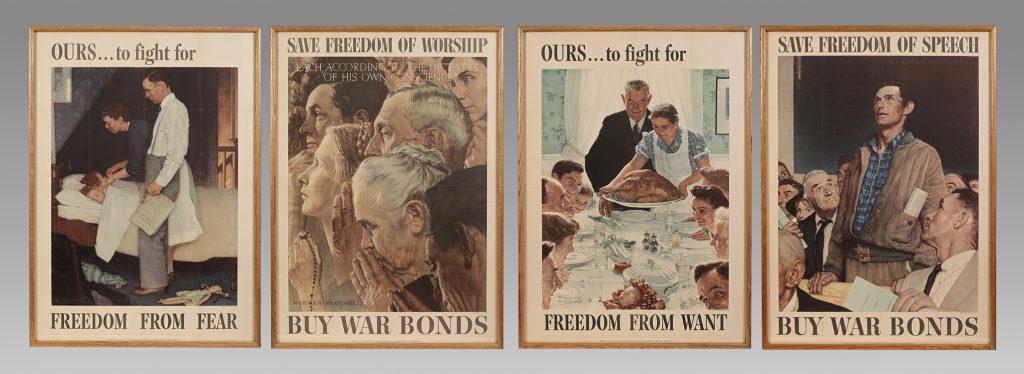

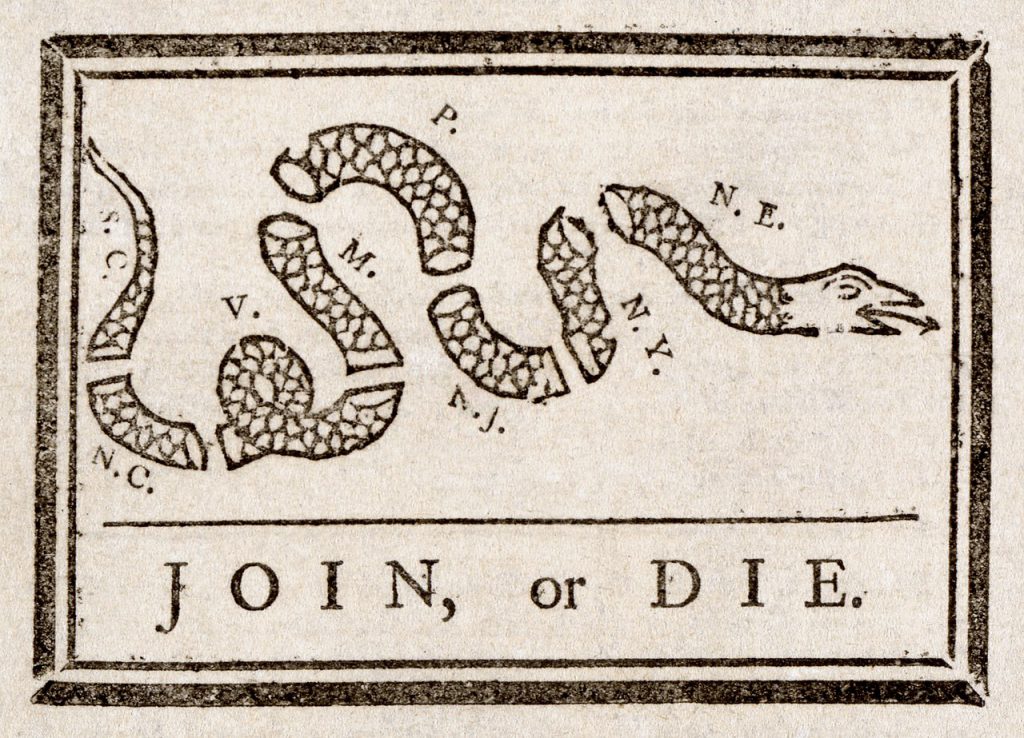

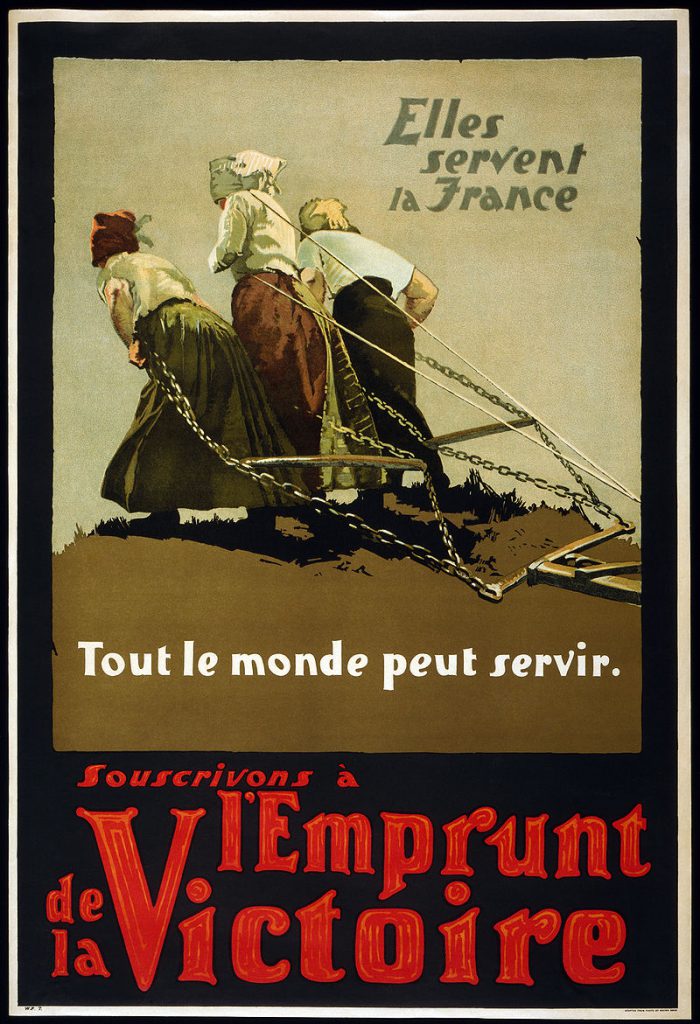

For the most successful and prolific years of his career, Szyk was a propagandist. By the time the Second World War broke out, propaganda art was a well-established genre, a far cry from Ben Franklin’s rabble-rousing “Join, or Die” cartoon. A brief look at World War I propaganda posters illustrates the progression: the posters may have sold bonds and urged enlistment, but they were also beautifully executed by established artists on both sides of the trenches. Even Picasso’s masterpiece “Guernica,” protesting the Nazi test-bombing of a Spanish town, was created to fulfill a commission for the Paris World’s Fair–thereby garnering global support for the plight of the Spanish Republicans. Political art had come into its own.

Credit: LOC.

Credit: PBS.org

Arthur Syzk had a natural journey to political art. He was born in 1894 in Russian-occupied Łódź. Although Syzk was Jewish, he was from a highly assimilated non-Orthodox family and considered himself Polish, even Polish nationalist. His political awareness set in early–he reportedly drew sketches of the Boxer Rebellion at the age of five or six.

Syzk’s artistic promise was clear by his teenage years. His father, Solomon, though blinded by acid during the Łódź Insurrection (an anti-Russian worker uprising) when Szyk was just 11 years old, was so confident in his son’s talent that he decided to send him to Paris to study art.

Like many aspiring artists of the era, Szyk landed at Académie Julian. The Académie attracted talent from around the world as well as within France, boasting alumni including John Singer Sargent, Henri Matisse, Diego Rivera, and Robert Rauschenberg. For Szyk, the Académie provided both technical training and the opportunity to be a part of Paris’ thriving artistic culture. Yet, Szyk remained deeply connected to Łódź. Szyk even secured a remote position as a political artist for the Polish satirical magazine Smiech.

Credit: Arthur Szyk Society

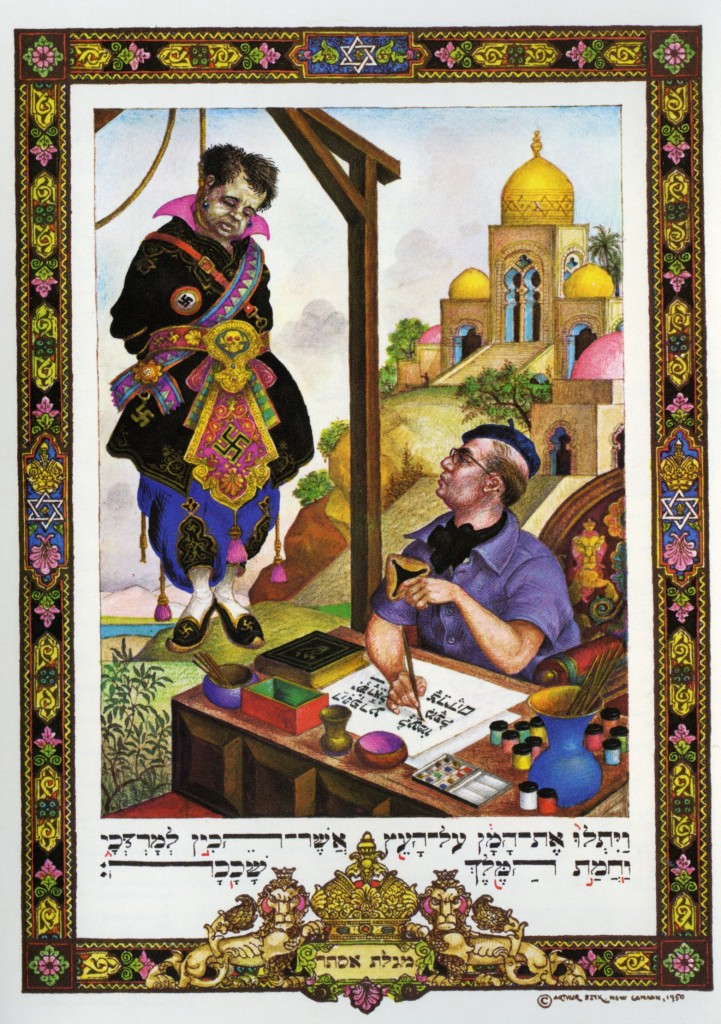

Szyk, though often regarded as a World War II artist, first achieved success during the Interwar years. While he had served as the artistic director of the propaganda department of the Polish army in Łódź during the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-20, his career truly blossomed after he moved back to Paris in 1921. Reviving a childhood interest, he returned to Biblical stories–often depicted with a political slant. His first book in this style was the Book of Esther (1925), in which he included himself in The Hanging of Haman and added swastikas to the image to pointedly reference Nazi persecution of the Jews (already well underway).

Credit: Jewish Museum Milwaukee

While he had been political before, Szyk was galvanized by Hitler taking power in 1933. He moved to London and quickly became a leading caricaturist, known for his pointed criticism of the Nazi regime. One of his greatest works was accomplished during this period–The Haggadah–but in order to publish it in London in 1937, he was forced to alter the contents (including painting over numerous swastikas) as the British were still pursuing appeasement. It was nevertheless a success, garnering critical acclaim and selling out the 250 limited edition copies produced. It was also the most expensive book in the world at the time–accounting for inflation, it would cost nearly $10,000 today.

The outbreak of war drove Szyk toward overtly political art once again. Unlike many propaganda artists of the time who concentrated on the heroism of Allied leaders, Szyk focused on the Axis powers. He showed Hitler, Mussolini, and the other Axis leaders as grotesque villains, ridiculously puffed up in their military outfits but still threatening and sinister. He also carefully depicted the ongoing suffering of the Jews and Poles, especially children, confronting the war atrocities head on as few were willing to. War Orphans is a compelling example of this type of art.

In July 1940, Szyk moved to North America. The British government and the Polish government-in-exile sent him there on assignment, asking him to shore up support of the British and the Poles. Working for companies and institutions ranging from Coca-Cola to the White House, Szyk strongly influenced the way Americans views the war. In fact, Szyk dedicated himself to being FDR’s “soldier in art.” When Roosevelt gave his iconic speech about the Four Freedoms, Szyk turned it into art–a full two years before Rockwell would do the same. (At Bauman Rare Books, we love both versions.)

Szyk remained in America and remained political for the rest of his life. While he did some of his most beautiful book illustrations in the postwar years including The Canterbury Tales, The Book of Job, and more, he returned to political art whenever he deemed it necessary. His work on behalf of Jewish refugees nearly landed him in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee. In 1951, Szyk died tragically of a heart attack. Fortunately, he left behind a political, historical, and–above all–beautiful body of work that is every bit as desirable today as it was during his life.