VISION. Not only the ability to see, but the ability to see far, sight unlimited by society???s blinders and smokescreens. Occasionally, even, to glimpse the future. Gazing westward in the 19th century, many could see the potential for progress and profit ??? that did not require vision ??? but few could see the people already living there, or chose to see them only as obstacles.

Written by David Bauman

Three Easterners, however, saw past the differences of skin color and custom to recognize the Native Americans??? essential humanity. They could see these many tribes as separate nations, with rich histories and diverse cultures. And they could see quite clearly what was in danger of happening as the young nation continued its relentless westward drive: the disappearance of the American Indian.

These three men ??? Thomas McKenney, George Catlin, and Edward Curtis ??? consciously dedicated large portions of their lives to preserve for posterity all that was vanishing before their eyes. Their monumental efforts, made at the cost of great personal sacrifice, form the bedrock for much of our knowledge about the American Indians ??? their stories, their histories, their cultures. How they appeared, how they spoke, how they sang, the stories they told. How they lived.

Thomas McKenney could not help but see what was happening. For years, he oversaw Indian trade ??? the so-called ???factory system?????? and then, in 1824, he was appointed head of the newly-created Office of Indian Affairs, a position he held until 1830, when he and President Andrew Jackson fell out over the ???Trail of Tears??? that resulted from the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Before his removal, however, McKenney had used federal funds to assemble a tremendous archive dedicated to the American Indian, an invaluable collection of books, manuscripts, artifacts and paintings.

The core of the collection was a gallery of some 150 oil portraits of prominent Indian men and women, most of them painted by Washington artist Charles Bird King during official visits of Native American delegations to Washington.

After his fall from governmental grace, McKenney dedicated himself to publishing lithographic reproductions of King???s oil paintings, with the goal of educating the American public and preserving these spectacular images for posterity. The History of the Indian Tribes of North America, including 120 lithographs, each one finely colored and finished by hand, was finally finished in three enormous folio volumes in 1844, some 15 years after McKenney and his writer-collaborator James Hall had begun working on this project.

George Catlin abandoned a career as a lawyer to dedicate himself to painting. He had established himself as a society portraitist in Philadelphia, when a visit to the city by a delegation of Native Americans captivated his imagination. ???The history and customs of such a people, preserved by pictorial illustrations, are themes worthy of the lifetime of one man,??? he wrote, ???and nothing short of the loss of my life shall prevent me from visiting their country, and becoming their historian.???

Against the advice of family and friends, he moved to St. Louis. Enlisting the aid of William Clark (of Lewis & Clark fame), he began to make forays into the frontier.

Catlin distinguished himself from McKenney and other artists by traveling and even living among the native peoples he was painting. He did so for the next eight years, returning periodically to St. Louis to finish his rough field sketches, until by 1837, he had completed his ???Indian Gallery???: more than 400 oil portraits, landscapes and genre paintings. His gallery was a success back East.

It was even more wildly popular when he took his paintings, together with eight tons of Indian artifacts ??? and eventually Native peoples themselves ??? to London, where his show enthralled audiences for five years. In 1845 the French king invited Catlin to move his gallery to the Louvre, and the French received him with equal acclaim.

It was during this time abroad that he published his landmark 1841 Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs and Conditions of the North American Indians, richly illustrated with line reductions of his original paintings, which can be found uncolored and colored (in later editions). In 1844 he published his Indian Portfolio, a collection of 25 folio-size hand-colored engravings, perhaps to rival McKenney???s work. Not unlike Catlin, Edward Curtis began his career making society portraits.

The span of a generation or two made for signifi cant differences, however: Curtis lived in Seattle, much further west than would have been feasible in Catlin???s time, and his artistic medium was photography, rather than oils and canvas. But, like his predecessor, Curtis longed for a project worthy of a lifetime???s dedication. Traveling to Montana in 1900 to witness the Blackfoot Sun Dance, Curtis found his inspiration.

???The passing of every old [Native American] man or woman means the passage of some tradition, some knowledge of sacred rite possessed by no other,??? he wrote. ???Consequently, the information that is to be gathered, for the benefit of future generations, respecting the modes of life of one of the greatest races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost for all time.???

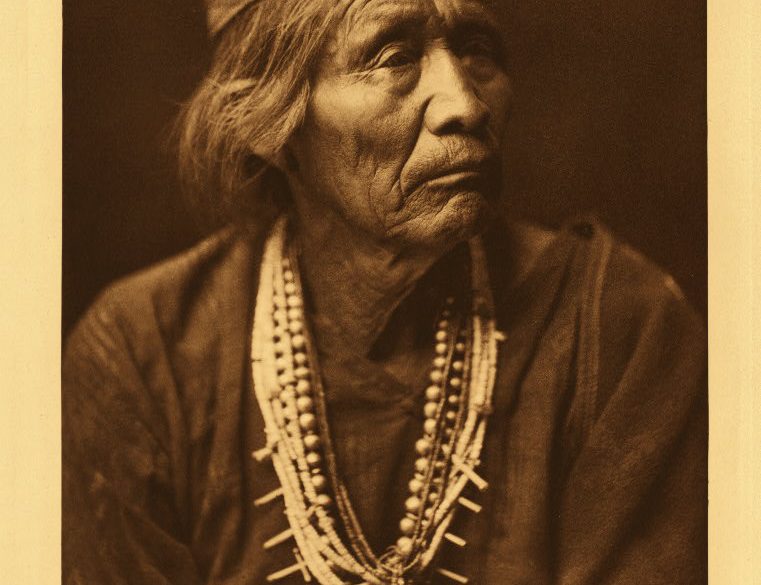

Over the next three decades, working mostly with a 6×8-inch reflex camera, he took more than 40,000 sepia-toned photographs, collected more than 350 traditional tales, and made more than 10,000 cylinder sound recordings of Indian speeches and music.

Under the title The North American Indian, Curtis set about publishing his work in a lavish edition that would reach 20 volumes with associated portfolios for each, printing some 2,200 photogravure images: portraits, landscapes, scenes of daily life, ceremonies, architecture and artifacts. The work was sold by subscription, but of the projected print run of 500 copies, it is now believed that only 272 complete sets were actually bound and sold.

Commercial failure, in fact, unites all three of these visionaries. Granted, their various publications were quite expensive at the time they were issued. Now, however, the original asking prices of a few dollars seem trivial: McKenney???s History of the Indian Tribes and Catlin???s Indian Portfolio ??? both large folio works with painstakingly hand-colored lithographs ??? regularly command well over $200,000. And a complete set of Curtis???s North American Indian, with the 20 text volumes (each richly illustrated in their own right) and the accompanying 20 portfolios, would now sell for more than $1,000,000.

At the time these monumental works were issued, it would seem that most of the general public simply could not see the value.

They were more focused, perhaps, on the golden future promised ???out West??? than on these recordings of the fleeting present, on these already dated shrines to people that were rapidly being relocated, vibrant cultures in danger of being relegated to the pages of history. But if fame and fortune were fleeting for these dreamers, their visions proved lasting and true.

Their lovingly detailed and enduring records have granted us a glimpse ??? they have fundamentally shaped our vision ??? of a vitally important era in our collective history.