We may brave human laws, but we cannot resist natural ones.

It is a great irony of 19th century literature that Jules Verne owed the inspiration for his first success to another author—who had virtually been forgotten by his own countrymen. After struggling to find success as a short story writer and as a playwright, Verne didn’t leap into fame and fortune until the publication of his first novel Five Weeks in a Balloon (Cinq semains en ballon, 1863). This first novel was influenced by Baudelaire’s translation of an American author who died unremarked in his own country: Edgar Allen Poe. Let’s trace this particular tapestry of influences, woven from one great author to the next, over the past two centuries–through the story of Verne’s best known novel.

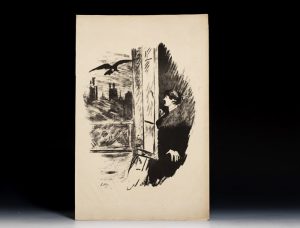

A plate from the magnificent 1875 French edition of the Raven, translated by Baudelaire and illustrated by Manet.

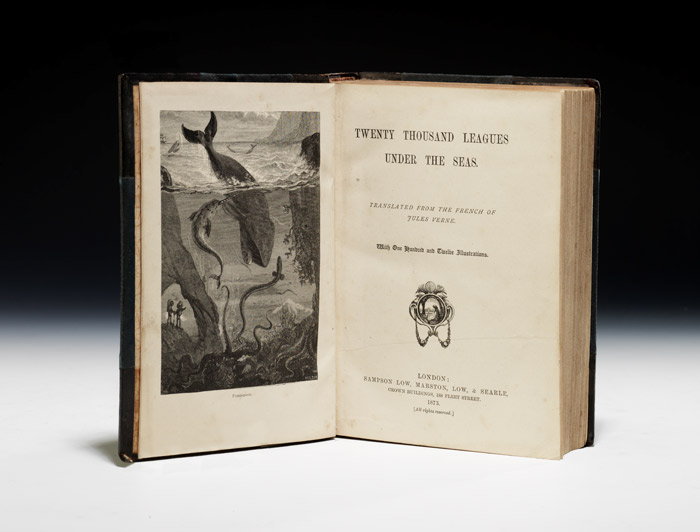

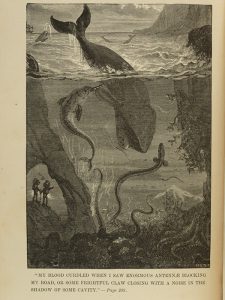

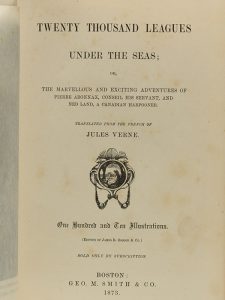

As I mentioned, Jules Verne was a remarkably successful novelist from the publication of his first book. But perhaps his most beloved novel, Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea (Vingt mille lieues sous les mers, 1870), would not have been published without an additional stimulus from another author, this one a bit closer to home.

The French novelist George Sand had already well-established her name in the literary world (via Verne’s own publisher, Hetzel) by the time she wrote to Jules Verne in praise. Her 1865 fan letter remarked,

Soon I hope you’ll take us into the ocean depths, your characters traveling in diving equipment perfected by your science and your imagination.

Thus inspired, Verne quickly completed his current project, In Search of Castaways (Les Enfants du capitaine Grant, 1867), and moved onto a story that explored the ocean depths with a mysterious rebel.

This new story consumed Verne. In an 1868 letter to his publisher Hetzel, he states:

I’m working furiously…This unknown man must no longer have any contact with humanity…the sea must provide him with everything. …Oh, my dear Hetzel, if I don’t pull this book off, I’ll be inconsolable. I’ve never held a better thing in my hands.

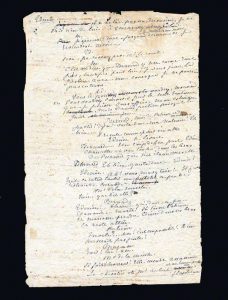

The “unknown man” was, of course, Captain Nemo. (“Nemo” is Latin for “no one.”) However, the captain’s birth and development in Verne’s manuscript was far from easy. Verne had been influenced in this case not by another author, but by a major world event: the 1863 uprising in Poland against Russia. He initially described Nemo as a brilliant Polish refugee seeking revenge against the Russian czar who had massacred his family. The publisher Hetzel immediate nixed it.

Sales of Verne’s works were quite profitable in Russia, and Hetzel wasn’t about to step into a political wasp nest. He told Verne the work was unpublishable in its current state. Verne’s reply was a turning point in his career as a writer, and also sheds some light on his view of the enigmatic protagonist he created:

Your letter greatly disturbed me for two days, and I wanted to reflect much on it before responding.

I see now that you are imagining a fellow very different from my own. And this is very serious, even more serious because I am totally incapable of depicting what I don’t feel. Obviously, I don’t see Captain Nemo as you do.

… In explaining him in a different manner, you change him to such an extent that I can no longer recognize him….

(Letter from Verne to Hetzel, May 17, 1869)

But Hetzel was to continue influencing Verne. In the end, the compromise between Verne and Hetzel resulted in a particularly compelling trait of the novel: Nemo’s past and motivations remain murky.

While the book was wildly popular, Verne suffers even today in the English-speaking world at the hands of critics and popular audiences as “only” a genre or children’s fiction writer. Leaving aside the (significant!) issue of demoting an author who is accomplished in such areas, Jules Verne actually reads quite differently in French. Most translations until about the 1970s and 1980s were horribly inept–not to mention translators had the habit of cutting large portions of the text. The first English translation of Leagues was cut by about one fifth. Some easy examples of translation fails from this novel include:

“Et armé d’une lentille, il alluma un feu” should be translated as: “And armed with a magnifying lens, he started a fire.”

Instead, it’s translated as: “And provided with a lentil, he lighted a fire.”

“les mauvaise terres de Nebraska” should be translated as “the Badlands” but instead became “the disagreeable territory of Nebraska.”

Readers, please see Walter James Miller’s Annotated Jules Verne: Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea (1976) to learn more about the problems of English translation and Miller’s pioneering efforts in fixing them.

Suffice to say the French originals offered much more complexity and depth than English readers received for decades. As a result, Verne’s literary influence in the French world surprisingly (to an English-speaking audience) extends to the French avant-garde circles, particularly surrealists.

But the weft of influences slides into science, as well. Verne named his submarine the Nautilus, after American engineer Robert Fulton’s early experimental submarine. Two decades later, American naval architect Simon Lake created designs for a submarine that would become the first to operate successfully in the open sea (the Argonaut) after reading Twenty Thousand Leagues. Verne sent Lake a congratulatory telegram.

Verne’s story of influence goes on and on. He inspired people as diverse as Rimbaud and Shackleton, Hubble and Cocteau—all different, yet all brilliant. Who knows what future readers of Verne will contribute in their turn?

Comments

4 Responses to “Twenty Thousands Leagues Under the Sea: The Influences of Jules Verne”

Dave Needham says: October 21, 2013 at 11:03 pm

The first English translation of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was done by Lewis Mercier, who was both a poor translator and not technically educated. As a result, the early English version of the novel contained many errors and was criticized by English critics, who thought the errors were Verne’s. Unfortunately, many modern English editions, published by companies more concerned by profit, than by accuracy, repeat the errors. It is more profitable to re-print a long ago edition (now public domain, but with errors), than to pay royalties to a modern scholar who may provide a better translation.

Rebecca Romney says: October 22, 2013 at 10:10 pm

You got it. My examples were from the Mercier translation, a man whose virtue was more speed than accuracy.

Harley Martin says: October 22, 2013 at 2:47 am

I have a copy of that book from 1911. I found it VERY difficult to read, but now I know why! Interesting & clarifying facts. Thanks!

sagorika thousen says: September 9, 2015 at 11:35 pm

by reading this adventures book I came to many things about the bottom of sea to its depth though its an imaginary story but it feels like true .Wow what a adventure they did..!!!