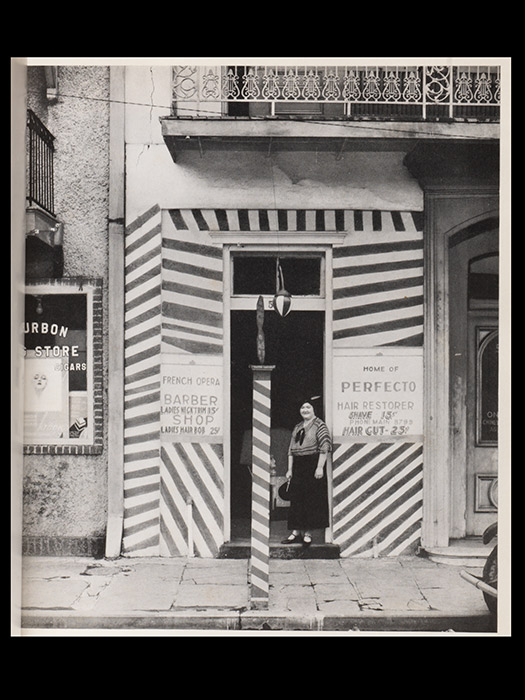

Travelling the land of the free, Walker Evans released photography in America from a cultural lockdown. By training his eye on the effects of the Depression era, he redrew the visual landscape and placed the country firmly at the center of attention.

Gone was the nostalgia associated with photography. In its place were images that would result in the first solo show of photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art—a feat accomplished just six years after Walker first took up photography. These images and this show urged people to view the world they thought they knew in an altogether different way.

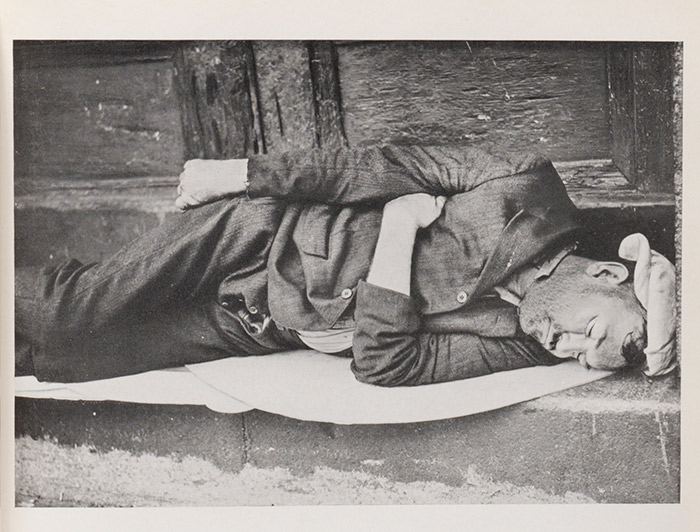

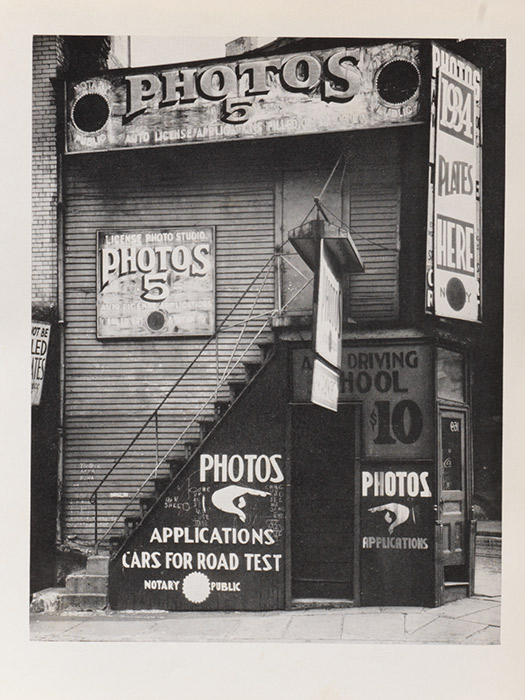

It was a time of social and rural transformation for the country, and in recording these changes, Evans was asking the viewer to remember these times. Moments of labor consumed by idol toiling, gas stations that seem to be running dry, row upon row of developed housing, and the aesthetic duality of advertising gone awry. Forget not the remaining wooden churches of the countryside, the forlorn plantation houses and farm land. Don’t ignore torn movie posters or parked cars. They are all beautiful in their own unique ways.

Perhaps more importantly Evans was asking for photography, indeed art, to be left out of the picture. Photographers were finally being recognized for the work they were creating in their own right, and in response Evans created a remarkably accurate and well-edited collection, one that Lincoln Kirstein described in his introduction as a composition in verse.

“The eye of Evans is open to the visible effects, direct and indirect, of the industrial revolution in America, the replacement by the machine in all its complexities of the work and art once done by individual hands and hearts, the exploitation of men by machinery and machinery by men…Walker Evans eye is a poet’s eye. It finds corroboration in the poet’s voice.”

It is believed Evans spent more time choosing images and laying out pages for this book than he did on constructing the exhibition. Perhaps he saw the permanency in store for his work over the transient nature of a show as more demanding of his time. Or perhaps it was because he believed in the document a book of photographs provides. Whatever his reasons, one thing is for sure: these images are a straightforward look at the subject matter which is simple, elegant and refined.